Making Sense of Recent Shifts in Environmental Policy — And What To Do About It

BY RICHARD R. SCHNEIDER

Twelve years ago, Alberta had an epiphany. We came to understand that the future we were constructing was not the future we wanted to live in. This idea was crystallized in a groundbreaking document called the Alberta Land-Use Framework, which contained the following preamble:

“What worked for us when our population was only one or two million will not get the job done with four, and soon five million. We have reached a tipping point, where sticking with the old rules will not produce the quality of life we have come to expect. If we want our children to enjoy the same quality of life that current generations have, we need a new land-use system.”

A Promise Made

The Land-Use Framework was the culmination of more than a decade of effort involving a wide range of stakeholders, land managers, planners, and researchers. A landscape modeling effort, led by Brad Stelfox, was a pivotal contribution. It allowed stakeholders and managers to understand the future consequences of existing land-use practices and to explore alternative paths.

The Land-Use Framework formally acknowledged that “our watersheds, airsheds and landscapes have a finite carrying capacity.” By analogy, rather than seeing the land as an all-you-can-eat buffet, as we did in the past, we saw a pie. The Land-Use Framework was a guide for dividing this pie in a balanced and fair way to achieve economic, environmental, and social goals — the so-called triple bottom line.

The Land-Use Framework also captured the idea of working toward a desired future through regional planning rather than simply accepting the unintended and unhappy consequences of unstructured development. In a finite landscape, we can’t “have it all.” But we can make optimal choices by identifying tradeoffs at an early stage and dealing with them proactively. This is particularly important for managing the effects of cumulative industrial impacts, which are not easily unwound once ecological tipping points are reached. Planning also provides the opportunity for integrating competing viewpoints in a structured and constructive way.

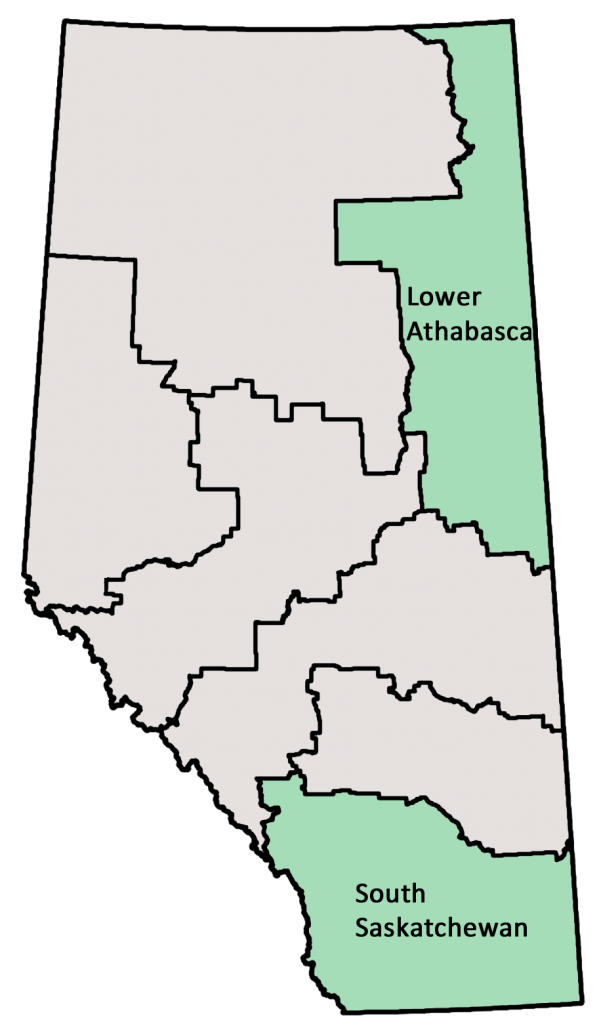

In practical terms, the Land-Use Framework divided the province into seven regions and established guidelines for developing integrated plans within these regions (Fig. 1). It called for the implementation of a cumulative effects management approach, with defined limits on the effects of development on the air, land, water, and biodiversity of the region. Within these limits, industry would be encouraged to innovate in order to maximize economic opportunity. It also called for extensive consultation in the development of these regional plans.

In summary, the Land-Use Framework embodied a promise. With government providing leadership and support, we would work together to achieve the best possible outcomes for Albertans, both current and future, by balancing economic, environmental, and social objectives within the limits of a finite landscape.

A Promise Deferred

The Land-Use Framework was released in 2008 and the first regional plan, involving the Lower Athabasca Region, followed in 2012. This initial plan was intended to serve as a template for future plans, which were expected to follow in quick succession.

Because the Lower Athabasca Region contained most of Alberta’s oilsands deposits, considerable planning had already been done, giving the planning team a running start. Nevertheless, the intention to tackle fundamental tradeoffs was never realized. In the end, the Lower Athabasca Regional Plan became a “plan to plan.” For example, it deferred the management of air, water, and biodiversity to a set of future management frameworks that would set targets for selected indicators and established triggers for proactive intervention. In other words, the difficult bits were kicked on down the road.

The notable exception to this pattern of decision deferment was the identification of new protected areas. In an effort to offset environmental damage arising from oilsands development and other industrial activity in the southern half of the planning region, several new protected areas were identified in the northern half of the region, mostly in lands adjacent to Wood Buffalo National Park. When these sites finally received legal designation in 2018, the combination of new and existing sites formed the largest contiguous boreal protected area in the world. This stands as a notable achievement of the planning effort.

Management frameworks for air quality and for the quality and flow of water in the Athabasca River were quickly developed, drawing on preliminary frameworks that were already in existence. The frameworks for biodiversity and cumulative effects did not fare as well. Like a car running out of gas, these planning initiatives sputtered on for a bit and then eventually ground to a halt. All that was accomplished was a draft framework of biodiversity indicators. The difficult task of identifying biodiversity targets that balanced regional environmental and economic goals was never addressed. Nor was a management plan for cumulative effects ever developed, despite the explicit commitments and deadlines in the Lower Athabasca Regional Plan.

As for the rest of the province, the only other plan to be completed was for the South Saskatchewan Region, in 2014. Like its northern counterpart, it was again a “plan to plan” that deferred difficult trade-off decisions to future management frameworks. Work on a biodiversity framework for the region was started but never completed.

A Promise Betrayed

When the NDP came to power in 2015, many believed their commitment to environmental protection would manifest as renewed attention to regional planning. It didn’t happen. The regional planning process remained in limbo throughout their tenure. In fact, when the NDP launched habitat protection initiatives in northwest Alberta and in the foothills (i.e., the Bighorn), they completely bypassed the regional planning process.

The election of the UCP in 2019, marked an abrupt change. The new government launched a virtual tsunami of policy changes related to environmental management. Land-use planning is now no longer in limbo — it is in full-scale retreat. The key changes are as follows:

- Removing parks. In a press release titled “Optimizing Alberta Parks,” the government announced the removal of 164 parks from the Alberta parks system. The list included 12 provincial parks — three of which face complete closure — and nine natural areas. The removal was characterized as a cost-saving measure; however, the $5 million in expected savings amounts to just 0.009% of the provincial budget — an essentially inconsequential amount. Moreover, while the establishment of the parks system entailed decades of effort and extensive public consultation, the decision to remove parks from the system involved no public consultation whatsoever. Had the government spoken to Albertans, they would have discovered that 69% were opposed to the closures.2

- Selling public lands. From a conservation perspective, the retention of public lands is sacrosanct. These lands are our natural capital, held in trust for future generations. Moreover, it’s not replaceable — we can’t make more land. Once public land is sold, decisions about how it is managed fall to the private owners. In theory, measures to maintain biodiversity can be mandated through government regulations. But in practice, this rarely happens, even when the habitat of endangered species is involved. The Kenney government seems unconcerned with these issues and is instead reviving attitudes prevalent in the 1980s, where the economic potential of land is the only metric that matters. This has manifested in the promotion of Crown land sales in the Peace Country and in the southern prairies. These land sales are occurring without public consultation or even notification.

- Increasing forest harvesting. In a news release on May 4, 2020, the government announced a 13% increase in annual allowable cut across Alberta’s forests. The title of the announcement was “Increased access to fibre helps protect jobs.” Displaying a mastery of political doublespeak, the release also stated, “When done sustainably, forest management can be used to help restore critical wildlife habitat over the long term.” There was no examination of the ecological effects of the increase in forest harvesting and there was no public consultation about the changes.

- Rescinding the Coal Policy. The Rocky Mountains and adjacent foothills are Alberta’s ecological crown jewels. This is one of the few remaining places where large mammal communities remain intact. Recognizing the special nature of this region, the Alberta government enacted the Coal Policy in 1976 to maintain its integrity. Four management zones were created, describing different levels of environmental sensitivity and tailored restrictions on development. On June 1, with no public consultation, this policy was rescinded. Open pit mines will now be permitted in 1.4 million hectares of environmentally sensitive Category 2 lands, where they had previously been prohibited. Robin Campbell, president of the Coal Association of Canada, estimates there are “at least a half a dozen” companies currently looking at developing mines on lands where it would have been previously prohibited and “there will be more.”3 According to the government, the Coal Policy was no longer required “because of decades of improved policy, planning, and regulatory processes.”4 The reality is that we have had decades of false starts, but little meaningful progress in planning within the region.

- Reducing environmental oversight. The dismantling of environmental oversight is also evident in the recently announced Bill 22, the Red Tape Reduction Implementation Act. The idea underpinning this act is that industrial development is being hindered by unnecessary rules. According to Minister Grant Hunter, the goal is to speed up the process and “take politics out of the regulatory decision-making process. ”5 But of course, land-use decision-making is inherently political, as it involves navigating trade-offs among competing societal objectives. Much of the “red tape” the government is keen on sidestepping represents constraints that were put in place to balance economic and environmental objectives. With this act, the government is signaling its rejection of the triple bottom line as a guiding principle and is instead reverting to a narrow focus on development at any cost.

- Hunting cranes and swans. Sandhill cranes and tundra swans have never been considered game species in Alberta. Yet, the Minister of Environment and Parks, Jason Nixon, recently asked his department to look into establishing hunting seasons for both species.6 The danger here is that sandhill cranes are easily mistaken for whooping cranes and tundra swans are easily mistaken for trumpeter swans. The slow, painstaking recovery of whooping cranes and trumpeter swans may therefore be jeopardized. Given the lack of broad public support for this initiative, or even strong demand within the hunting community, why is the government pursuing this? According to Hugh Wollis, a retired Alberta Fish and Wildlife biologist, the demand for a hunting season is being driven mainly by outfitters eager to serve their U.S. clientele. It would appear that a small but effective lobby is overriding the broad public interest, which the minister has made no attempt to gauge.

Making Sense of It All

Land-use policy changes in Alberta over the past 15 years can be divided into three distinct phases. In the first phase, a broad range of stakeholders became increasingly concerned about the cumulative effects of unmanaged development. These stakeholders included not only environmental advocates but also prominent industrial players who saw that their social licence to operate depended on sustainable industrial practices that balanced economic, environmental, and social objectives. It was clear to everyone that no individual company or sector could tackle this issue independently. What was needed was a common set of land-use objectives and a system of integrated planning.

As the issue rose to prominence, the government became engaged, and when Ed Stelmach was elected as premier in 2006, regional planning became a cross-ministry priority. Under Stelmach’s direction, extensive public consultations about land-use objectives took place, leading to the paradigm shift described at the beginning of this article.

The defining features of this first phase of policy change were concern and support from a broad range of stakeholders for tackling cumulative effects and a government that was willing to listen and take action. In short, the issue had political momentum and a champion.

The second phase of policy change began during the final stages of the development of the Land-Use Framework. During this period, several factors conspired to hinder the regional planning process and eventually bring it to a halt. To begin, the scope of the process was allowed to expand too broadly. What began as an initiative to integrate industrial activities and manage cumulative effects became a catch-all for everything from economic diversification to providing recreational opportunities. As a result, the process became bogged down in complexity, leading to the deferment of key decisions.

The initiative also struggled against internal government divisions and resistance to change, particularly from the proponents of economic development. Moreover, the governance system needed for integration at the regional scale was lacking. Finally, the emergence of the Wild Rose Party, and its misinformation campaign about regional planning (farmers and ranchers beware: they are trying to take away your rights!), turned the Land-Use Framework into a political liability instead of an asset.

When Stelmach resigned as premier in 2011, the initiative lost its champion and political attention drifted elsewhere. The hope that the NDP would revive the regional planning process after their election was not fulfilled. When it came to environmental issues, their focus was on climate change. Also, as a new government, they may have seen regional planning as beyond their capacity. Or perhaps they distrusted a process so closely associated with the previous government. Whatever the case, planning came to a complete halt under their watch.

In summary, the second phase was characterized by a progressive loss of political will accompanied by flagging stakeholder interest, as it became apparent that substantive change was not going to happen. The government maintained its commitment to the principles of the Land-Use Framework, but there was no gas left in the tank for implementation.

The third phase of land-use change began with the election of the UCP government in 2019. The policy changes in this phase, characterized by a hard shift away from environmental protection and planning in general, are hardest to understand. Though fiscal prudence was a core element of the UCP platform, cost-cutting is at best only a partial explanation for the abrupt change in direction. For example, the decision to close parks will have no discernible effect on the overall provincial budget. Nor will incrementally selling public land or shooting swans. Fiscal prudence also fails to explain the consistent pattern of avoiding public consultation or the willingness to undertake actions contrary to the broad public interest.

One possible explanation is simple vindictiveness. The Kenney government is clearly incensed by opposition to pipeline construction, which they perceive as being driven by environmental groups. In what amounts to blind fury, they seem to be lashing out at anything related to environmental protection.

Another possible explanation is that the recent policy changes reflect political strategy. The UCP knows its primary vulnerability is not from the NDP, but from vote splitting with a right-wing party, as happened in 2015. Therefore, taking a page from Donald Trump’s playbook, the best strategy is to cater to the far-right elements of your base and ignore everyone else. Rational decision-making and serving the broad public interest are not requirements under this approach. The key is to serve your base by tapping into grievances, providing scapegoats, and offering solutions that resonate with preconceived ideas, whether or not they are likely to succeed.

What to Do?

The pattern of policy changes in recent months suggests that the commitments made in 2008 to balance economic, environmental, and social goals through regional planning have been abandoned. We have regressed to the 1980s, when economic development was all that mattered. However, the problems with unfettered development that were acknowledged in the Land-Use Framework have not gone away. Things are only getting worse.

Turning the ship around will not be easy. Kenney’s government seems intransigent and quite prepared to ignore public opinion. But there are already indications that this approach is untenable. According to a recent poll, a majority of Albertans feel that the province would be better off with a different premier — a disapproval rating far higher than for any other premier in Canada.7 Clearly, ignoring the broad public interest is not a sound long-term strategy.

Naturalists are generally a quiet, reflective lot, preferring to spend their time in the field, interacting with nature, rather than marching in the street. But current circumstances demand that we stand up and defend what we love. It’s time to raise our collective voice in support of nature. We are not foreign “Current circumstances demand that we stand up and defend what we love. Environmental decline is not the legacy we want to leave for future generations.” interests bent on destroying Alberta’s economy. We are home-grown Albertans who know that sacrificing the health of our environment in the name of development is not a recipe for prosperity. This is not the legacy we want to leave for future generations.

Please write to Premier Jason Kenney (premier@gov.ab.ca) and Minister of Environment and Parks Jason Nixon (aep.minister@gov.ab.ca) and let them know your thoughts on the recent spate of policy changes. Remind them of the importance of balancing economic growth with environmental protection. And ask them to revive the regional planning initiatives and public consultations required to achieve that balance. A short 12 years ago, these topics held a prominent position on the political agenda. If enough people speak up now, it can happen again. It has to.

Richard Schneider is a conservation biologist with over 25 years experience working on land-use policy in Alberta. He is now serving as the Executive Director of Nature Alberta.

References:

- Alberta Land-Use Framework. Government of Alberta, 2008.

- Alberta Omnibus Survey. Leger, March 18, 2020. URL: https://cpawsnab.org/wp-content/ uploads/2020/03/CPAWS-OMNI.pdf

- Alberta rescinds decades-old policy that banned open-pit coal mines in Rockies and Foothills. CBC news report, May 22, 2020.

- Information Letter 2020-23. Government of Alberta, 2020.

- Government’s red-tape legislation stumps the NDP and the minister who tabled it. CBC news report, June 12, 2020.

- Alberta environmentalists oppose possible crane, swan hunting season. CBC news report, Apr. 3, 2020.

- 56% of Albertans don’t want Jason Kenney as premier, poll suggests. CBC news report, May 29, 2020.

This article originally ran in Nature Alberta Magazine - Summer 2020, Volume 50 | Number 2