Battling Lethal Bacteria in Wild Bighorn Sheep

5 July 2024

BY MARK BOYCE

About five years ago I edited a special issue of The Journal of Wildlife Management on controversial issues in the management of mountain sheep. We invited contributions from leading researchers and managers of mountain sheep in North America on a broad range of research topics. The message was clear that the biggest threat to bighorn sheep is disease spread by contact with domestic sheep or goats. Indeed, disease has been a major contributor to the decline and local extirpation of many bighorn populations during the past century.

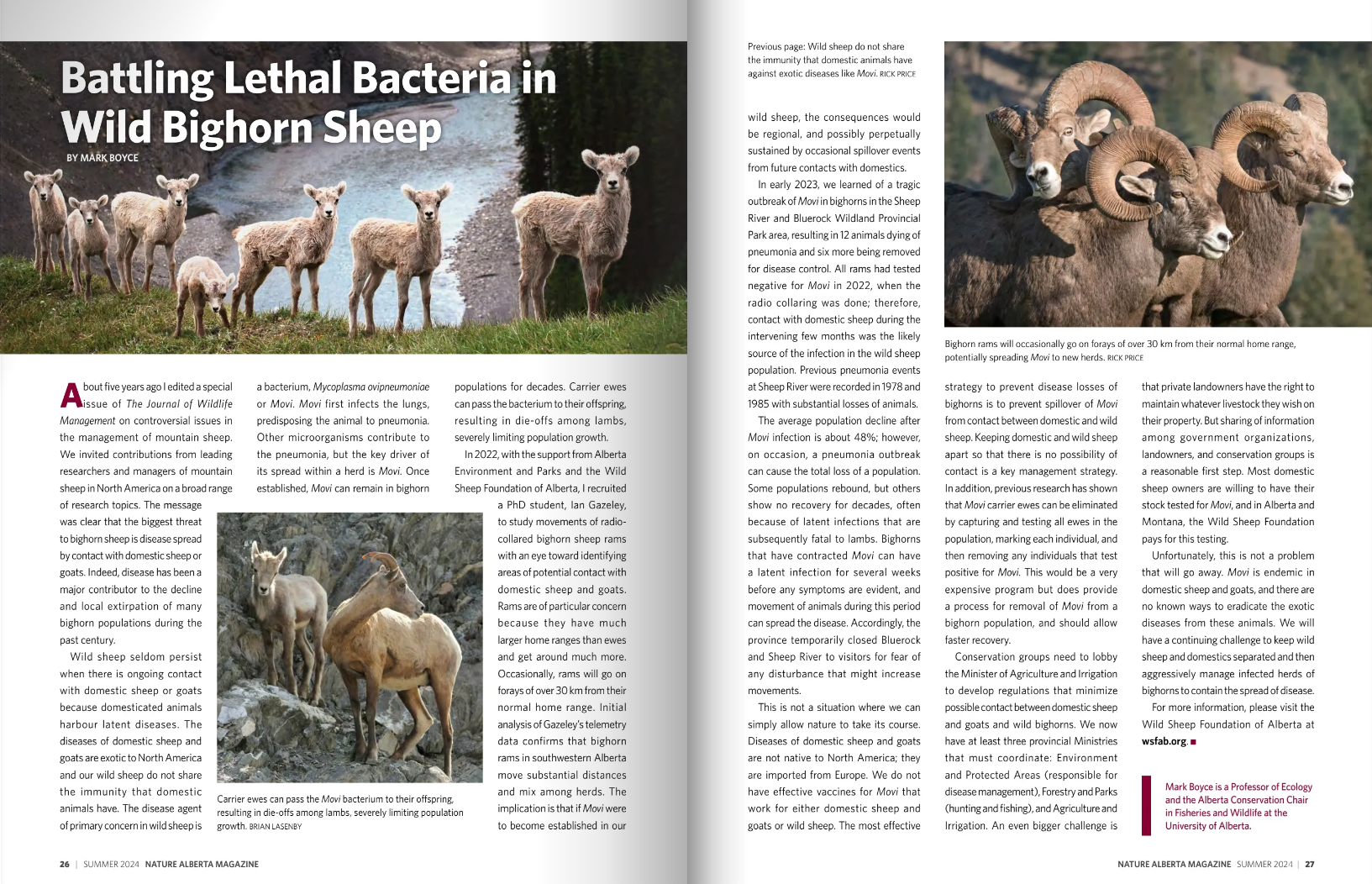

Wild sheep seldom persist when there is ongoing contact with domestic sheep or goats because domesticated animals harbour latent diseases. The diseases of domestic sheep and goats are exotic to North America and our wild sheep do not share the immunity that domestic animals have. The disease agent of primary concern in wild sheep is a bacterium, Mycoplasma ovipneumoniae or Movi. Movi first infects the lungs, predisposing the animal to pneumonia. Other microorganisms contribute to the pneumonia, but the key driver of its spread within a herd is Movi. Once established, Movi can remain in bighorn populations for decades. Carrier ewes can pass the bacterium to their offspring, resulting in die-offs among lambs, severely limiting population growth.

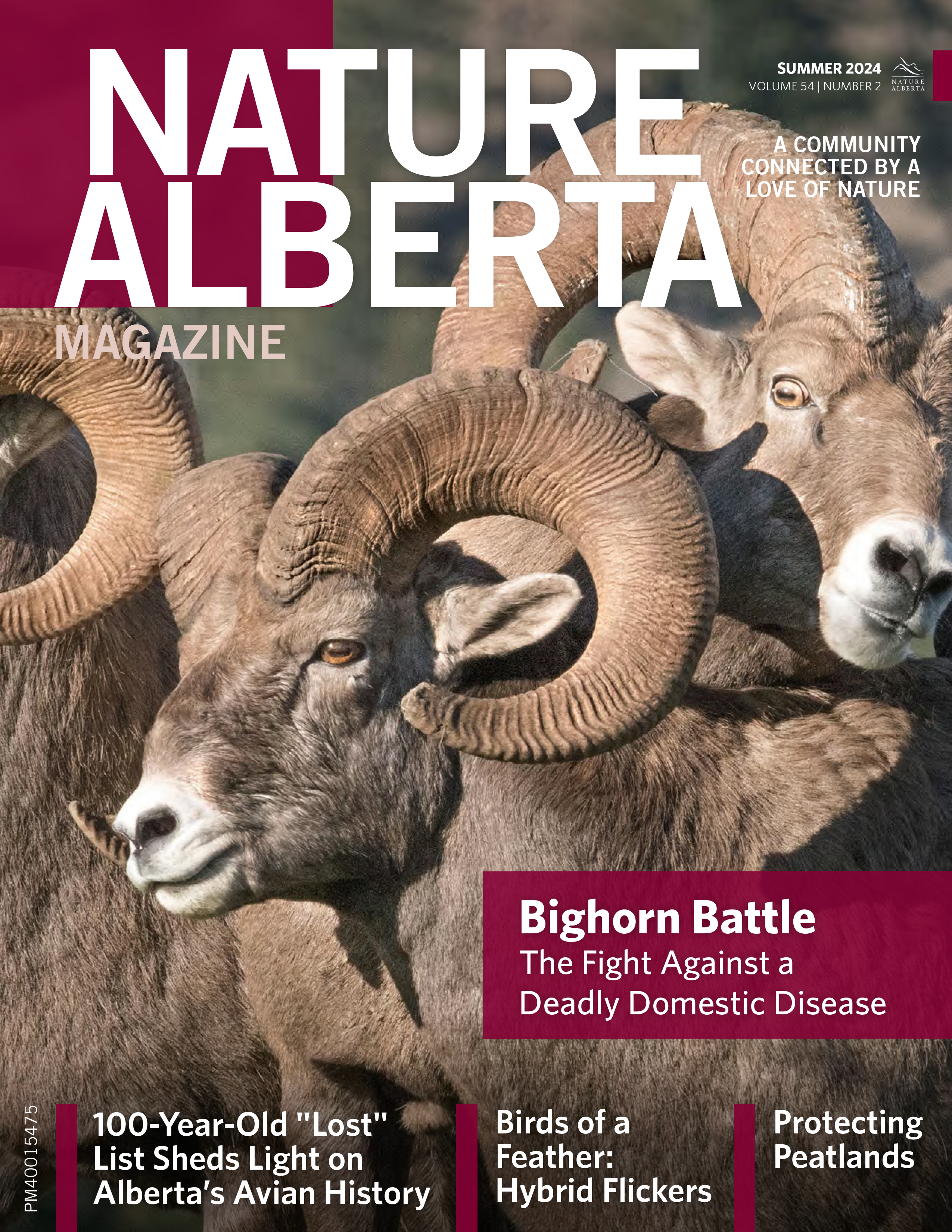

In 2022, with the support from Alberta Environment and Parks and the Wild Sheep Foundation of Alberta, I recruited a PhD student, Ian Gazeley, to study movements of radio-collared bighorn sheep rams with an eye toward identifying areas of potential contact with domestic sheep and goats. Rams are of particular concern because they have much larger home ranges than ewes and get around much more. Occasionally rams will go on forays of over 30 km from their normal home range. Initial analysis of Gazeley’s telemetry data confirms that bighorn rams in southwestern Alberta move substantial distances and mix among herds. The implication is that if Movi were to become established in our wild sheep, the consequences will be regional, and possibly perpetually sustained by occasional spillover events from future contacts with domestics.

Carrier ewes can pass the Movi bacterium to their offspring, resulting in die-offs among lambs, severely limiting population growth. RICK PRICE

In early 2023, we learned of a tragic outbreak of Movi in bighorns in the Sheep River and Bluerock Wildland Provincial Park area, resulting in 12 animals dying of pneumonia and six more being removed for disease control. All rams had tested negative for Movi in 2022, when the radio collaring was done; therefore, contact with domestic sheep during the intervening few months was the likely source of the infection in the wild sheep population. Previous pneumonia events at Sheep River were recorded in 1978 and 1985 with substantial losses of animals.

The average population decline after Movi infection is about 48%; however, on occasion, a pneumonia outbreak can cause the total loss of a population. Some populations rebound, but others show no recovery for decades, often because of latent infections that are subsequently fatal to lambs. Bighorns that have contracted Movi can have a latent infection for several weeks before any symptoms are evident, and movement of animals during this period can spread the disease. Accordingly, the province temporarily closed Bluerock and Sheep River to visitors for fear of any disturbance that might increase movements.

This is not a situation where we can simply allow nature to take its course. Diseases of domestic sheep and goats are not native to North America, they are imported from Europe. We do not have effective vaccines for Movi that work for either domestic sheep and goats or wild sheep. The most effective strategy to prevent disease losses of bighorns is to prevent spillover of Movi from contact between domestic and wild sheep. Keeping domestic and wild sheep apart so that there is no possibility of contact is a key management strategy. In addition, previous research has shown that Movi carrier ewes can be eliminated by capturing and testing all ewes in the population, marking each individual, and then removing any individuals that test positive for Movi. This would be a very expensive program but does provide a process for removal of Movi from a bighorn population, and should allow faster recovery.

Conservation groups need to lobby the Minister of Agriculture and Irrigation to develop regulations that minimize possible contact between domestic sheep and goats and wild bighorns. We now have at least three provincial Ministries that must coordinate: Environment and Protected Areas (responsible for disease management), Forestry and Parks (hunting and fishing), and Agriculture and Irrigation. An even bigger challenge is that private landowners have the right to maintain whatever livestock they wish on their property. But sharing of information among government organizations, landowners, and conservation groups is a reasonable first step. Most domestic sheep owners are willing to have their stock tested for Movi, and in Alberta and Montana, the Wild Sheep Foundation pays for this testing.

Unfortunately, this is not a problem that will go away. Movi is endemic in domestic sheep and goats, and there are no known ways to eradicate the exotic diseases from these animals. We will have a continuing challenge to keep wild sheep and domestics separated and then aggressively manage infected herds of bighorns to contain the spread of disease.

For more information, please visit the Wild Sheep Foundation of Alberta at wsfab.org

Mark Boyce is a Professor of Ecology and the Alberta Conservation Chair in Fisheries and Wildlife at the University of Alberta.

Read the Original Article for this Post

For a richer reading experience, view this article in the professionally designed online magazine with all images and graphs in place.

This article originally ran in the Summer 2024 issue of Nature Alberta Magazine (Vol. 54 | No. 2).