Badgers With Benefits

11 February 2025

By NIKKI HEIM

One cool spring morning, while crouching amid a few towered boulders on the edge of an open grassy field, I watched dirt fly and heard ground squirrels squealing. A female badger was on the hunt. She moved back and forth between a ground squirrel-laden field and her burrow on the other side of a gravel township road, which she paused at before each crossing as if checking for traffic. Upon each arrival at her burrow, a pair of smaller striped faces would appear. With two hungry mouths to feed, she was no doubt eager to make a kill. I remained quiet and still because badgers are most sensitive to human disturbance in the spring when rearing their young. With no apparent awareness of my presence, she began to move in my direction. I tucked myself low so as not to alarm her. My whole reason for being here was to observe her movements in her natural state.

I was assisting a graduate student with outfitting badgers with GPS backpacks so he could estimate badger population dynamics and monitor their movements, specifically where their habitat was intersected by roads. Little is known about badger population distribution or abundance across Alberta and the Prairie provinces, but biologists have identified road mortality as the leading threat to badger survival. Additional threats include continued loss of native prairie; habitat conversion for agriculture and urban development; and removal of badgers and their primary prey, ground squirrels, via poison or shooting. With much of our remaining grassland habitats bisected by roads, badgers are often struck by vehicles when moving across the landscape. Badgers not only travel across roads but are often found burrowing in friable soils typical of roadsides and cut banks, leaving them increasingly vulnerable to passing traffic. Gaining a better understanding of movement patterns within their home ranges might aid in mitigating the number of badgers being struck by vehicles. Being part of this research afforded me a unique opportunity to observe — and grow fond of — these lesser-known carnivores.

Badgers give birth to an average of one to two kits, which disperse from their mothers by May or June. Juvenile female badgers typically disperse up to 52 km from their birthplace, while males disperse farther, up to 110 km. Similarly, home range sizes for individual badgers vary substantially by sex, ranging from as little as 2 km2 to up to 300 km2, depending upon geographic location and prey availability. Badgers mate between July and August, live up to six years in the wild, and are generally solitary.

The badger continued to advance towards me, each step inciting squirrely alarm bells. Within moments, she was standing just in front of me, sniffing the base of the boulder. I watched her nose lift, presumably picking up my scent. She peered through a break between the boulders. She had found me! With obvious surprise, she quickly turned and retreated, nearly as hastily as the panicky ground squirrels she’d been hunting moments before. Still crouched on my perch, I was thrilled. This brief and close interaction did not fit with the fierce or aggressive attitude I had been warned of before taking the job.

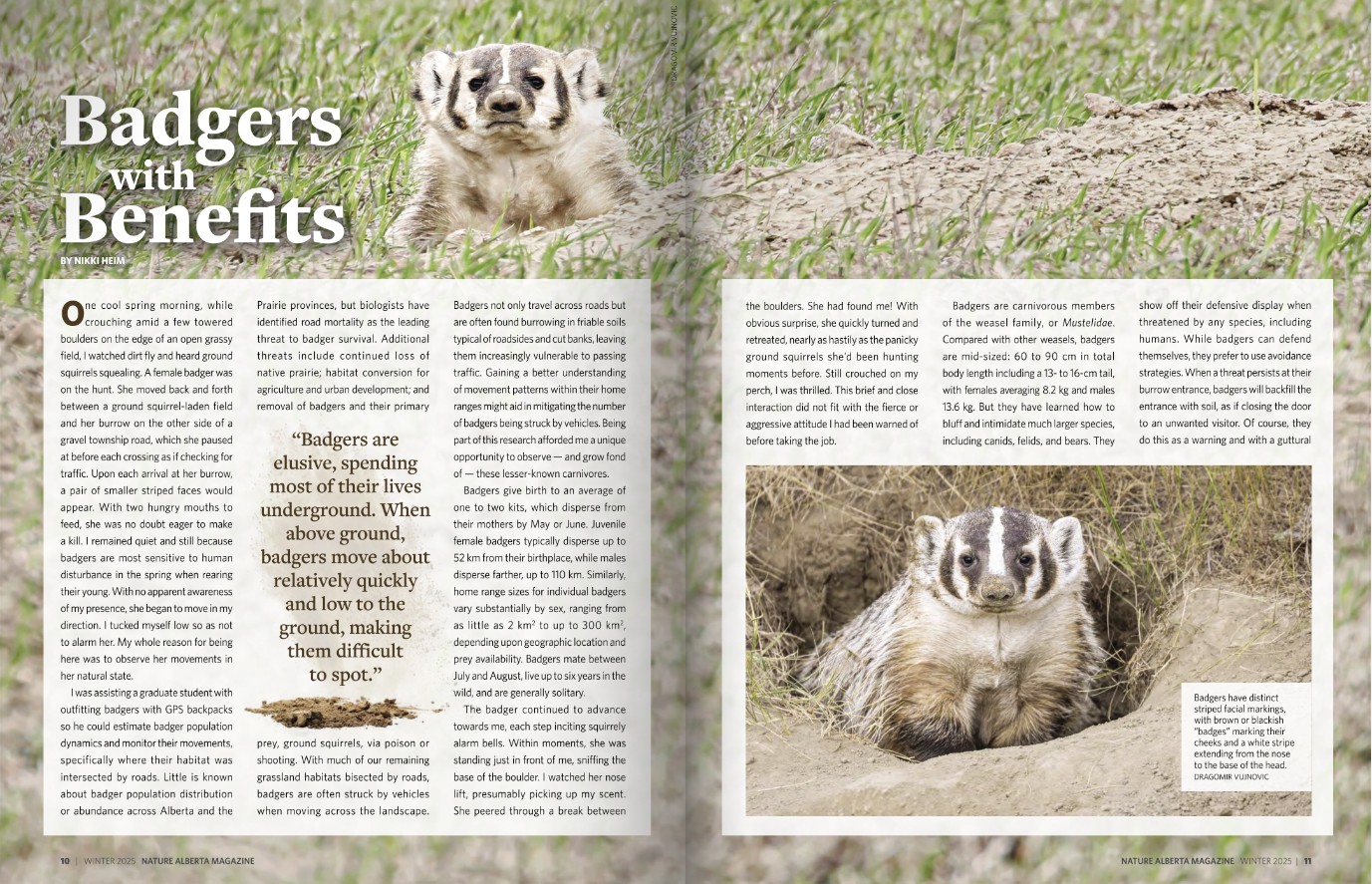

Badgers are carnivorous members of the weasel family, or Mustelidae. Compared with other weasels, badgers are mid-sized (60-90 cm in length, with females averaging 8.16 kg and males 13.6 kg), but have learned how to bluff and intimidate much larger species, including canids, felids, and bears. They show off their defensive display when threatened by any species, including humans. While badgers can defend themselves, they prefer to use avoidance strategies. When a threat persists at their burrow entrance, badgers will backfill the entrance with soil, as if closing the door to an unwanted visitor. Of course, they do this as a warning and with a guttural growl that gives the impression they’re about to turn and bite. It’s not until it is cornered or confronted by a persistent threat that a badger would bite. When asked if badgers are dangerous, I like to suggest refraining from sticking your hand in a burrow should you wish to keep all your fingers. Badgers have very sharp teeth, mainly used for hunting and consuming prey.

Badgers have evolved to dig. Their long, showy claws, more round than sharp, are excellent digging tools that can make quick work of a road cut, open meadow, or pasture, and are highly effective at moving rock and ripping through tree roots. They dig large holes, or burrows, which are an integral part of any badger’s life history. Badgers have flat, oblong bodies, short legs and ears, and loose skin around their necks, allowing them to squeeze into shallow holes and tunnels. Burrows are used for safety, shelter, and resting, for birthing and rearing their young, and for storing food. Badger burrows can have a single entrance or multiple entrances with a series of underground chambers and tunnels, called setts. These extensive networks are used generationally; some are estimated to be over 100 years old.

Badger burrows provide numerous benefits to grassland ecosystems that often go underappreciated or simply unnoticed — as cryptic as the animal itself. DRAGOMIR VUJNOVIC

Badgers are elusive, spending most of their lives underground. When above ground, badgers move about relatively quickly and low to the ground, making them difficult to spot. When met with a human or a wild competitor, badgers quickly retreat to the nearest underground sanctuary, making them even harder to spot. Because they are rarely observed during the day, badgers are often mistakenly assumed to be nocturnal. People living and working in the Alberta foothills and prairies can observe badgers at all times of day; most people, however, will likely never see one, much less have a conversation about them.

For landowners and operators, large badger holes with large soil mounds are sometimes perceived as hazards to machinery, horses, and cattle. To reduce this risk, direct or indirect persecution via shooting or secondary poisoning of their prey is the most common management action. Though badgers pose some known risks, the benefits they may provide are greater and act as a good indicator of range health.

Badgers are generalist predators that hunt everything from bird eggs to reptiles to slightly larger mammals, such as muskrats, but small mammals make up most of their diet. Their preferred prey are rodents, such as ground squirrels and prairie dogs. Badgers are estimated to consume two to three ground squirrels per day and can knock a population of squirrels down by 50% while in the area. A healthy badger can have disproportionate impacts on foraging small mammals. As such, some contend that badgers are keystone predators in grassland systems. For a landowner, the reduction in ground squirrels could mean fewer ground squirrel holes as well as the retention of rangeland vegetation. For example, a few badgers capable of preying on over 300 ground squirrels in a summer season equates to 1 Animal Unit Measure (AUM) of feed for one cow-calf pair.

While a single badger is an effective hunter on its own, their success has been observed to be enhanced alongside a cooperative coyote. These two grassland predators coexist to improve each other’s hunting success, further regulating small mammal populations. Badgers and coyotes hunt differently — badgers dig and coyotes pounce. On the hunt, they take advantage of each other’s strategies. When a ground squirrel retreats from a badger and exits another hole, the coyote waits, ready to pounce. Conversely, a ground squirrel will retreat from a coyote by fleeing into a nearby burrow, where a badger can quickly dig it up. Coyotes and badgers have been observed travelling together, exhibiting behaviour towards each other that suggests a relationship that may be more than simply tolerance, but perhaps even friendship. With or without the company of a coyote, the badger’s ability to regulate small mammal numbers is highly beneficial in supporting healthy grassland systems.

Badger excavations and burrow networks can function as a natural disturbance, enhancing soil structure and composition, increasing water infiltration, soil aeration, nutrient cycling, and organic decomposition rates, as well as supporting vascular plant and soil invertebrate diversity. Badgers will move across the landscape, occupying areas for various periods of time. Vacant burrows become habitat for a wide variety of secondary users, such as western rattlesnakes, Great Basin spadefoot toads, and western tiger salamanders. Recovery strategies for endangered swift fox and burrowing owl also include supporting the presence of badgers.

Watch footage of a badger and coyote hunting together: bit.ly/badger-coyote-hunt. For more information about Alberta’s badgers, educational material, and to report observations, visit prairiebadger.ca.

Researcher Sheri Monk of the organization Snakes on a Plain, in Redcliff, Alberta, recently shared: “I’ve studied snakes for 20 years, and the more time I spend in snake habitat, the more I see the badger’s signature all around and throughout it. Snakes need badgers to secure access to suitable denning opportunities. Many snake hibernacula are in unstable ground, which can collapse. A healthy badger population ensures new potential den entrances are being created. Habitat is dynamic on the prairies, and badgers are the driving force behind that.”

Canada’s prairie grasslands, home to badgers and many obligate grassland species, are listed as one of the world’s most endangered ecosystems, with an estimated 74% already lost. At a time of climatic and ecological uncertainty, retaining healthy populations of species such as badgers may improve grassland resiliency and support habitat for fellow grassland species. Given the long list of beneficial contributions badgers provide, perhaps we can learn a little something from coyotes and explore ways to coexist for our mutual benefit. It’s not always easy to do, but it’s something I have thought about a lot since that morning when I watched that female badger hunt with utmost persistence to feed her two hungry kits.

Nikki Heim is a Wildlife Ecologist based in Canmore, Alberta who has spent the past 20 years focusing on better understanding medium- to large-sized carnivores across western Canada and the United States.

Read the Original Article for this Post

For a richer reading experience, view this article in the professionally designed online magazine with all images and graphs in place.

This article originally ran in the Winter 2025 issue of Nature Alberta Magazine (Vol. 54 | No. 4).