Singing Insects of Alberta

16 April 2025

By KEVIN JUDGE

It’s a warm, early July evening in William A. Switzer Provincial Park. My students and I stand motionless on the soft mat of Sphagnum on the forest floor, lodgepole pine and spruce scattered about us. All is quiet apart from the occasional truck travelling along Highway 40 in the distance, the intermittent drone of mosquitos buzzing about our heads, or the melodious song of a solitary hermit thrush. Then I hear it — a short, harsh trill off to our left. “There!” I exclaim, but I can tell by their excited whispers that the students noticed it too. Then we hear another trill to our right, longer and closer this time. The opening bars of the chorus of great grigs ring out into the darkening mountain air. Soon the sound from these singing insects will fill this leafy cathedral.

Great grigs are just one species of insect that sings. The term “singing” is usually applied to animals that produce sounds that either attract potential mates or deter rivals (or both) over distances. For most people, birds come quickly to mind — their melodic songs brighten the predawn in springtime. Familiar too are the songs of frogs and toads; think of the trilling of chorus frogs from ponds across the prairies. Less familiar are the singing insects. But when the forests, swamps, and plains of primordial Earth first resonated to the chorus of mating songs, the first performers were almost certainly not vertebrates, but insects.

How Insects Sing

It is no wonder that insects evolved song first; their bodies are covered by a hardened cuticle that almost inevitably makes noise during movement (think of a medieval knight walking in a suit of armour). Many insects do indeed produce noises during motion or while feeding, but only two orders have evolved the special ability to produce long-distance song: order Orthoptera, which includes crickets, katydids, grasshoppers, and relatives like the great grig; and the order Hemiptera, which includes cicadas.

Orthopterans produce sound by rubbing parts of their chitinous exoskeleton together in a process called stridulation. Crickets, katydids, and great grigs rub their forewings together, whereas grasshoppers rub their legs against their bodies and wings or snap their hind wings together during crepitation flights. Cicadas sing by rapidly popping flexible parts of their exoskeleton in and out, a process called tymbalation; think of the clicking sound when you press the button on the lid of a juice bottle, only at thousands of times per second. The fields, wetlands, forests, and urban areas of Alberta are alive with the songs of these insects from soon after the snow clears until the first hard frost in the fall.

Musical vs. Noisy Songs

Cricket songs are musical, and grasshopper sounds are noisy. This isn’t a matter of subjective taste; these two terms have specific meanings in the context of insect song.

Musical refers to the dominance of one frequency or a narrow band of frequencies in a sound. Musical insect songs are ones where you can hear a distinct note in the song and, provided you have the range, you would be able to whistle or sing along with it. Crickets and grigs sing musical songs, and we often use words like chirp and trill to describe them.

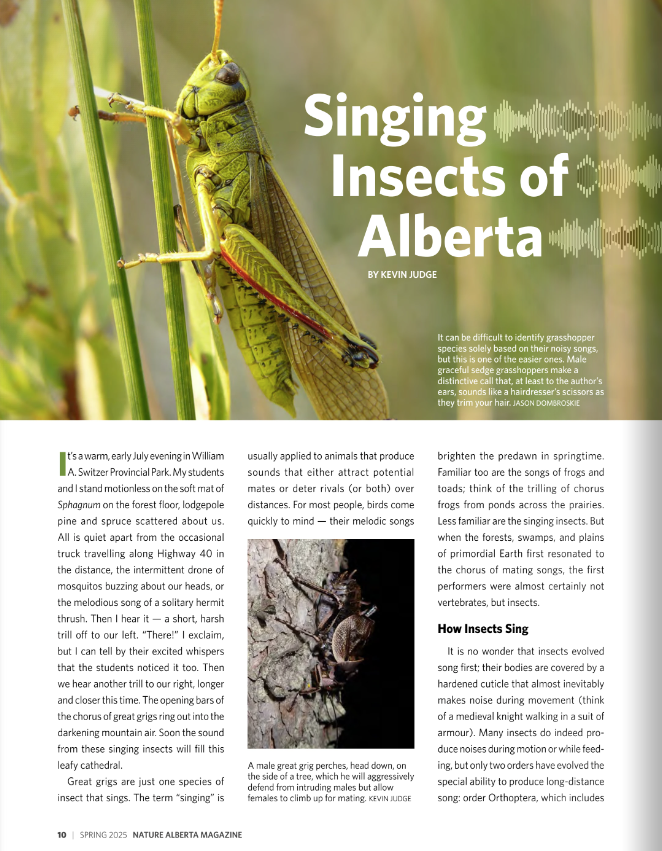

Noisy insect songs, on the other hand, have a broad range of frequencies present with none dominating. In this context, noisy does not equate with loud; many grasshopper songs are quite soft. Instead of distinct notes, you hear sibilant sounds like “sss” or “sh” or “ch” — we describe these sounds with words like buzz, rattle, hiss, and tick. Grasshoppers, cicadas, and katydids sing noisy songs.

Whether a song is musical or noisy can be used in combination with the location of the singer to help you identify what kind of singing insect you are hearing. For example, a musical song coming from the ground is likely a field or ground cricket, but if it’s coming from shrubs, it is likely a tree cricket, and from the trees in the mountains, it is a grig. A noisy song coming from the trees is almost certainly a cicada, from shrubs or tall grasses is likely a katydid, and from the ground or while flying is often a grasshopper.

Opening Act: Springtime Singers

Spring field crickets are among the earliest songsters to make themselves known in the grasslands of southern Alberta. These large, shiny-black crickets sing from burrows or cracks in the ground. But not just one song! Male spring field crickets, like several other singing insects, produce distinct types of song depending on the context. First, they produce a rhythmic, musical chirp that attracts females and repels rival males; this is the calling or advertisement song. Second, when a potential mate approaches closely, they switch to a courtship song: a softer, more raspy and continuous song punctuated by sharp “ticks” and the occasional chirp. Third, if a rival male intrudes, they will aggressively defend their territories, and the two males will often fight for supremacy. During the battle, one or both males may sing an aggressive song, which is a longer, drawn-out musical chirp that precedes all-out wrestling if neither male is intimidated enough to back off. Spring field crickets provide an example of how listening to song gives us a window into the complexities of insect social life.

The other early-season musicians are all grasshoppers, which are distinct from crickets in several important ways. Grasshoppers are from a different branch of the Orthoptera family tree, one that is characterized by having relatively short antennae, as opposed to the long, thin antennae of crickets and their closer relatives, the katydids and grigs. Grasshoppers are active during the daytime, whereas crickets and their kin are active in the dark, making vision much more important for the former than the latter. Perhaps because of the combination of these traits, grasshopper mating displays are often colourful affairs paired with acoustic signals.

The aptly named club horned grasshopper. Locating stridulating males can be frustrating as they seem to be constantly on the move and will stop singing when you get close, only to start up again a meter or two away. JASON HEADLEY

The speckle-winged rangeland grasshopper, perhaps the most common of the early-season breeders, offers an excellent example of the combined visual and acoustic mating display. At first glance it is the opposite of showy; its textured brown body blends in almost perfectly with the bare ground and dead grass of the spring. But this is a ruse. On a hot, sunny spring day, males leap into the air, snapping their brightly coloured yellow or reddish hind wings together — crepitation — to produce a noisy buzz that announces, “Here I am!” to the audience of receptive females and rival males. Males make long crepitation flights when alone, and short ones when approaching a female. Once a male has approached a female, he stridulates by rubbing his hind legs up and down against the outside of his forewings, simultaneously producing a noisy acoustic display and showing off a distinctive contrasting banding pattern on the inside of those hind legs. Grasshopper mating displays are often complex, varied, and, unfortunately, poorly studied in most species because of the difficulty of observing a highly visual and mobile insect in the wild.

Warming Up

Because singing is a metabolically demanding activity and insect metabolism varies with body temperature, which is largely determined by the surrounding environment, some species’ rate of singing has a strong relationship with environmental temperature. For example, the prairie tree cricket’s song tends to be faster in warmer temperatures and slower when it’s cool. It’s possible to analyze recordings of prairie tree cricket song and accurately calculate the temperature at the time of recording. So if the crickets are singing adagio, grab a jacket!

Songs of Summer

In between the spring-singing breeders and late-summer singers lie two groups that take advantage of the midsummer to engage in their mating season: the great grigs that you met in the introduction and cicadas, whose noisy, buzzing song is the soundtrack of hot, sunny midsummer days across Canada. Rarely seen because they usually sing from high in the trees, they nevertheless are widespread and relatively common. I’ve recorded males in the middle of downtown Edmonton, singing from the canopy of boulevard trees. Then, as the summer marches on, the last and largest cohort of singing insects takes centre stage.

Late summer days and warm evenings ring out with the trills and chirps of ground crickets, tree crickets, and the fall field cricket. This is also the season when we first encounter the persistent, noisy songs of katydids. How many of us have driven down a range road with the windows down and heard a constant rattling buzz from the grassy verge? This is the song of the gladiator meadow katydid. Males are spaced out by territorial aggression so that their individual loud calls appear to be constant as we drive past. More common, but less noticeable, are the calls of the slender meadow katydid — barely perceptible to adult ears because their noisy songs occupy frequencies in the upper range of human hearing — and the cautious, staccato calls of the broad-winged bush katydid, our only representative of the leaf-mimicking katydids. Common too, and possibly spreading, are the fascinating but confusingly named Mormon cricket and the non-native Roesel’s katydid. Finally, there are the myriad songs and displays of grasshoppers, such as the ubiquitous, soft churring of the marsh meadow grasshopper, the scissor-like rasping of the graceful sedge grasshopper, and the loud clacking crepitation flights of bandwing grasshoppers (wrangler, crackling forest, and Carolina bandwings, among others).

At this time of year, the air is truly filled with the music of an insect choir, each species singing its part. My fervent hope is that you will take some time to slow down, tarry a little on the walk, and listen to the insect symphony unfolding around us.

Concert Schedule:

Find a list of Alberta’s common singing insects, and when you can hear them, at naturealberta.ca/singing-insects-of-albertaInsect Playlist:

Give several species of singing insects a listen at youtube.com/@singinginsectsalberta5556

Kevin Judge, PhD, is an Associate Professor and the Resident Bug Guy in the Department of Biological Sciences at MacEwan University.

Read the Original Article for this Post

For a richer reading experience, view this article in the professionally designed online magazine with all images and graphs in place.

This article originally ran in the Spring 2025 issue of Nature Alberta Magazine (Vol. 55 | No. 1).