A Brave New (Natural) World: How Artificial Intelligence Can Supercharge Your Interactions With Nature

16 April 2025

By RICHARD HEDLEY

Artificial intelligence (AI) is a hot topic these days, its emergence receiving daily media attention for its potential to disrupt many aspects of our day-to-day lives. At the extreme, commentators have warned that AI will usher in widespread job losses — or possibly even the end of society as we know it. Less dramatic predictions contend that AI will amplify social media algorithms to keep us glued to our screens more than ever. Although these predictions may have merit, AI also has the potential to do the opposite: to encourage us to take our eyes off our screens to learn, appreciate, and rekindle lost connections with the natural world. An array of smartphone apps, such as iNaturalist and Merlin, freely available for download, can turn your phone into a pocket nature expert, ready to guide you through your backyard or nearby wilderness and reveal the secrets of the natural world.

Snapshot to ID in 60 Seconds

A recent personal experience opened my eyes to AI’s potential as a powerful learning tool. One morning last summer, as I was vacationing with my family in Ontario, I noticed a mass of more than a hundred of what looked like caterpillars devouring a pine tree. The sheer number of insects caught my eye, their weight causing the small branch to sag. Besides their numbers, it also struck me as unusual that caterpillars would so eagerly feast on an unpalatable pine tree, rather than the more appetizing deciduous foliage nearby.

“Huh,” I thought. “Interesting!” I took out my phone and snapped a photo.

Not so long ago, “Huh, interesting” is where the experience would have started and ended. What else could one do when faced with an unidentified agglomeration of insects? Spend hours in vain on Google Images trying to identify them? Send emails to an entomologist or a nearby natural history club with faint hopes of receiving a response, who knows how many days or weeks later? Perhaps a trip to the nearest library or bookstore to find an invertebrate field guide to search through. All options were tedious and unappealing. Undoubtedly, I would have gone for a swim instead, forgetting all about the insects I had encountered.

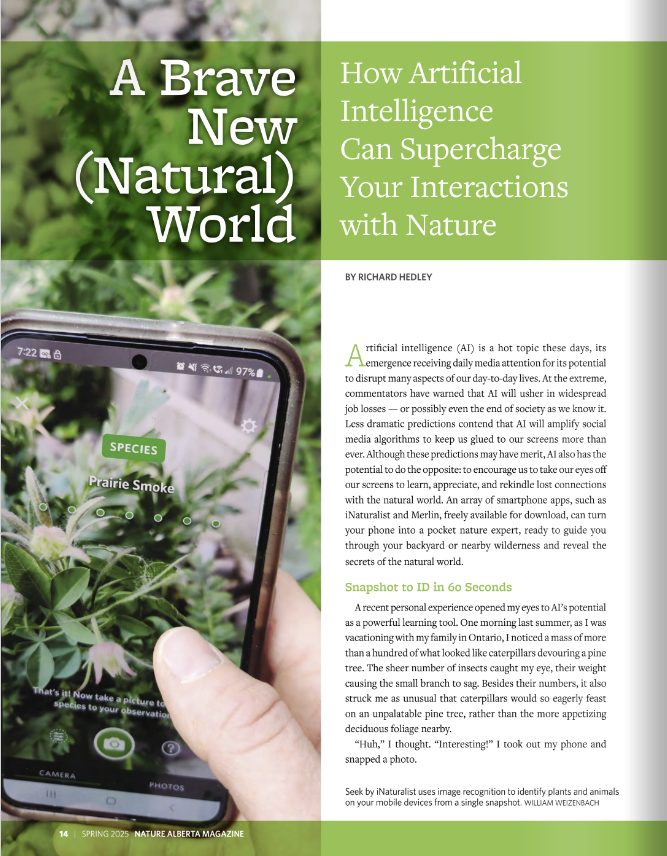

Today, advances in AI have presented us with an incredible new option of automatic identification. After snapping the photo, I uploaded it to the citizen science app iNaturalist. Moments later, the app provided me with a few identification suggestions. Red-headed pine sawfly popped up as the top suggestion. I’m no entomologist, but after perusing a few other photos of the species, I concluded that the suggestion was likely correct. Satisfied, I clicked submit, adding the observation to iNaturalist’s massive database.

Photographing and identifying this insect took about one minute. How long would it have taken me to identify it the old-fashioned way? I can only imagine, especially considering I began with a misguided belief that the insects were caterpillars — entirely the wrong insect order. Most importantly, by pointing out my error, the AI presented me with the opportunity to learn more about insect identification, a topic I have always found intimidating. I have since read (admittedly casually) about the ecology of red-headed pine sawflies, as well as articles explaining how to differentiate between caterpillars and sawfly larvae.

Thus, with very little fanfare, our phones have become personal assistants with specializations in entomology, not to mention botany, ornithology, ichthyology, herpetology, and just about any other “ology” you can imagine. As a biologist, I am surrounded by experienced experts in my professional and social life, and I am not exaggerating when I say my phone can now identify a greater array of species than anyone I know. This development has reduced an enormous historical barrier to entry faced by those newly interested in nature. Identification skills are, after all, the most fundamental skills of a naturalist, and only once they are acquired can one really start to discern patterns in the natural world: which species occur in which habitats, what eats what, which have declined or increased over time, and so on.

Identifying flora and fauna just got a whole lot easier. But how did this happen?

A Brief History of Automated Classification of Plants and Animals

Most media coverage of AI focuses on its applications in buzz-worthy fields such as self-driving vehicles, facial recognition, workflow automation, and chatbots like ChatGPT. Diverse as these applications may be, many AI tools are just high-performing image recognizers. It is in this realm — image classification — that AI saw its first major success in 2012, when an AI model named AlexNet crushed its competitors in a computer image recognition competition, transforming the field forever. The AlexNet model was based on a method called deep learning, a method that was first proposed decades prior, but was viewed as impractical and unwieldy. However, with sufficient computing power and access to enough data, AlexNet turned out to be far superior to the other competing algorithms. This success spurred intense research interest in the subsequent years, which in turn has led to the resurgent hype around AI that we see today.

The 2012 image recognition competition won by AlexNet focused on classifying photographs into 1,000 eclectic categories, everything from guitars to sundials. Identifying these objects may seem a far cry from identifying a bird, a plant, or my red-headed pine sawfly, which clearly requires significant attention to detail and memorization of field marks. Fortunately, computer scientists and biologists had been holding competitions of their own to automatically classify flora and fauna, and just a few years later, in 2015, the AI revolution spilled over into these competitions and dramatically improved the performance of the state-of-the-art algorithms. It turned out that, to a computer, pixels on a screen are pixels on a screen, regardless of whether they depict a plant, an animal, or a human-created object.

Around this time, the prospect of producing useful, real-world tools became tractable. Several such tools have since emerged. Popular nature-based apps include iNaturalist and Merlin. iNaturalist, the app that helped me identify the sawfly, has a truly impressive ability to identify photographs of a mind-boggling number of plants and animals. A related app called Seek turns nature enjoyment into a game by issuing challenges to users (for example, the insect challenge: find 10 different insects). Merlin, created by the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, is equally impressive in its ability to identify bird songs. To use it, simply press record and hold your phone up to the bird in question, and the app will suggest an identification. Despite my 15 years as a working ornithologist, this app has humbled me on at least a few occasions by identifying a bird song I was struggling with.

These apps are by no means perfect. In many cases, iNaturalist only suggests an identification to the family or genus level, which may not satisfy a diehard nature lover. That may not always be the algorithm’s fault; some photos may simply lack the detail needed to go further. In other instances, the suggested identification may not be correct, in which case expert reviewers may correct it. And if for some reason today’s AI doesn’t impress you, you can always wait a while. It has often been noted that the AI tools we use today are the worst we will ever use, so rapid is the development of the technology. What the next iterations may be capable of is anybody’s guess.

A Win-Win-Win for Biologists, Nature Lovers, and Conservation

Whether you are employed as a career biologist, enjoy nature with a casual curiosity on weekends, or simply care about the conservation of nature, the advent of AI-based identification tools is a watershed moment in the centuries-long history of the natural sciences. It is now possible to go outside and learn without cumbersome reference material or experts (possibly even more cumbersome) in tow.

For biologists, these tools can help collect more accurate data sets, for example by reducing the number of species that are written on datasheets simply as “unknown.” I know I’ve had my share of unknowns over the years. Less time flipping through field guides means more time doing the work that matters. AI also promises to dramatically increase the amount of data that biologists can collect, such as automatically processing images from camera traps or identifying sounds from acoustic recording devices placed in remote locations.

For nature lovers, apps can increase your enjoyment by opening your eyes to plants and animals you never knew existed. Your backyard, local green space, or favourite campsite contains a riot of diversity to be discovered. With patience and dedication, you can begin to disentangle a drama of predation, herbivory, pollination, and who knows what else, right under your nose.

From a conservation perspective, AI has transformative potential. Many species, especially species of conservation concern, can be difficult to find, in some cases known from just a few locations in the province. Their elusive nature means information on their distribution and abundance is often lacking. Filling in these basic data gaps can greatly facilitate efforts to conserve rare species, since you can only conserve something if you know where to find it. Fortunately, the best AI tools are designed to not only identify photos and sounds, but also add the records to public databases for use by researchers, government agencies, and other interested parties. Observations made by citizen scientists can help reveal new populations or monitor trends over time. Many species, notably plants and invertebrates, also suffer from a small and dwindling pool of experts with the skills needed to identify them. With AI helping you tackle the learning curve, the next expert might be you!

The technology is free to use, so you can head outside and start snapping photos or making recordings at any time. Or, if you want to participate in something bigger and more targeted, there are also several citizen science programs operating in the province, many of which are increasingly leveraging this technology. (See Nature Alberta News on page 3 for some upcoming citizen science initiatives.)

So, in an era when time on screens is vilified and time in nature revered, maybe it’s time to combine them to get the best of both worlds. Open one of these apps and see what they have to say about the plants and animals around you. You might just realize that modern technology is not so incompatible with the enjoyment of nature after all. Indeed, you might start to view your phone as a valued companion: the expert sidekick you never knew you needed.

Richard Hedley is a biologist and nature enthusiast who lives and works in Edmonton.

Read the Original Article for this Post

For a richer reading experience, view this article in the professionally designed online magazine with all images and graphs in place.

This article originally ran in the Spring 2025 issue of Nature Alberta Magazine (Vol. 55 | No. 1).