Alberta’s Peatlands

5 July 2024

BY TINA MCLEAN AND JAY WHITE

Wetlands come in a wide variety of shapes and sizes and support different types of plant communities. They are ecologically important landscape features, collectively covering approximately 20% of the province. A key defining feature of wetlands is that their average depth is less than two metres deep in the central or deepest part. Lakes are water bodies which are greater than two metres deep throughout the majority of the basin.

The wetlands you are most likely familiar with are marshes and sloughs — Alberta has millions of them. These wetlands are mostly found in the southern and central parts of the province. The rate of plant productivity is high, but so is the rate of decomposition, so these wetlands have mucky mineral soils with limited buildup of organic matter.

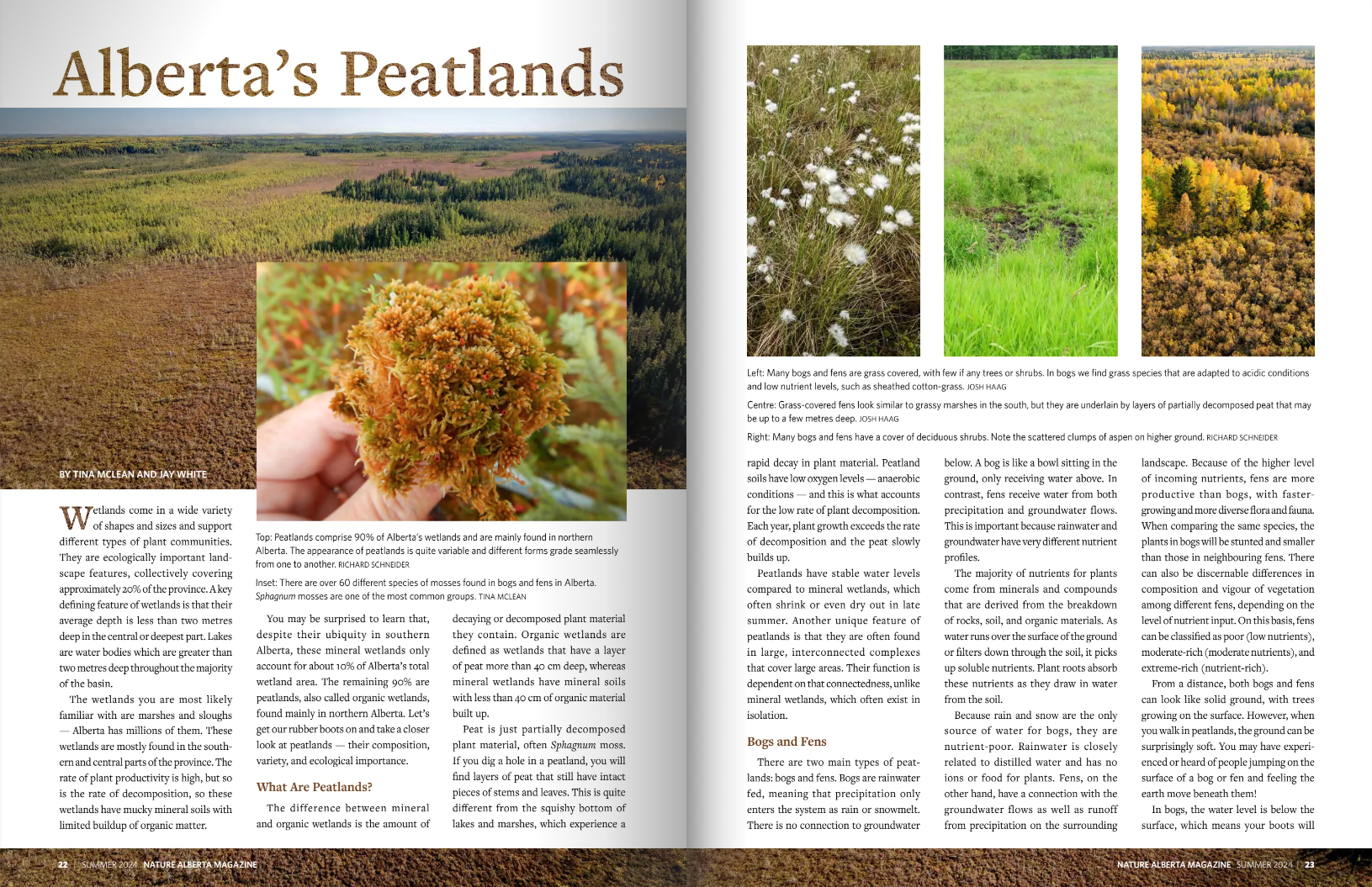

You may be surprised to learn that, despite their ubiquity in southern Alberta, these mineral wetlands only account for about 10% of Alberta’s total wetland area. The remaining 90% are peatlands, also called organic wetlands, found mainly in northern Alberta. Let’s get our rubber boots on and take a closer look at peatlands — their composition, variety, and ecological importance.

What Are Peatlands?

The difference between mineral and organic wetlands is the amount of decaying or decomposed plant material they contain. Organic wetlands are defined as wetlands that have a layer of peat more than 40 cm deep, whereas mineral wetlands have mineral soils with less than 40 cm of organic material built up.

Peat is just partially decomposed plant material, often Sphagnum moss. If you dig a hole in a peatland, you will find layers of peat that still have intact pieces of stems and leaves. This is quite different from the squishy bottom of lakes and marshes, which experience a rapid decay in plant material. Peatland soils have low oxygen levels — anaerobic conditions — and this is what accounts for the low rate of plant decomposition. Each year, plant growth exceeds the rate of decomposition and the peat slowly builds up.

Peatlands have stable water levels compared to mineral wetlands, which often shrink or even dry out in late summer. Another unique feature of peatlands is that they are often found in large, interconnected complexes that cover large areas. Their function is dependent on that connectedness, unlike mineral wetlands, which often exist in isolation.

Bogs and Fens

There are two main types of peatlands: bogs and fens. Bogs are rainwater fed, meaning that precipitation only enters the system as rain or snowmelt. There is no connection to groundwater below. A bog is like a bowl sitting in the ground, only receiving water above. In contrast, fens receive water from both precipitation and groundwater flows. This is important because rainwater and groundwater have very different nutrient profiles.

The majority of nutrients for plants come from minerals and compounds that are derived from the breakdown of rocks, soil, and organic materials. As water runs over the surface of the ground or filters down through the soil, it picks up soluble nutrients. Plant roots absorb these nutrients as they draw in water from the soil.

Because rain and snow are the only source of water for bogs, they are nutrient-poor. Rainwater is closely related to distilled water and has no ions or food for plants. Fens, on the other hand, have a connection with the groundwater flows as well as runoff from precipitation on the surrounding landscape. Because of the higher level of incoming nutrients, fens are more productive than bogs, with faster-growing and more diverse flora and fauna. When comparing the same species, the plants in bogs will be stunted and smaller than those in neighbouring fens. There can also be discernable differences in composition and vigour of vegetation among different fens, depending on the level of nutrient input. On this basis, fens can be classified as poor (low nutrients), moderate-rich (moderate nutrients), and extreme-rich (nutrient-rich).

From a distance, both bogs and fens can look like solid ground, with trees growing on the surface. However, when you walk in peatlands, the ground can be surprisingly soft. You may have experienced or heard of people jumping on the surface of a bog or fen and feeling the earth move beneath them!

In bogs, the water level is below the surface, which means your boots will get damp, but you usually will not see water pooling on the surface unless it’s springtime after the snowmelt or there has been a recent rain. Fens have visible water at or near the surface and flowing water may be noticeable. Take care when walking in fens as you may get more than your boots wet!

Did you know that bogs and fens are acidic? The Sphagnum moss species that grow in peatlands, especially bogs, purposefully acidify their surroundings, which allows them to out-compete many other plant species. Also, the process of bacteria and fungi breaking down the layers of dead organic matter produces acids.

Just how acidic are peatlands? Well, distilled water is neutral, with a pH of 7.0, and white vinegar (5% acetic acid) typically has a pH of around 2.5. Bogs are roughly as acidic as orange juice, with a pH typically ranging from 3.0 to 4.5. Fens are less acidic than bogs, with pH measurements ranging from 4.5 to 7.0. Fens have fewer Sphagnum moss species and more brown moss species, more nutrients, and more biodiversity.

Flora and Fauna

Alberta’s peatlands provide habitat for over 400 different species of plants, including trees, shrubs, forbs, and mosses, many of which prefer acidic conditions. Trees such as tamarack, black spruce, and bog birch are primarily found in peatlands, along with shrub species such as bog cranberry, willows, blueberries, and currants. Other plant species include brown mosses, Sphagnum mosses, water sedge, meadow horsetail, and dwarf bog rosemary.

Because of the poor nutrient levels and acidic conditions in bogs, unique plant species have adapted to live in this environment. Did you know that there are carnivorous plants in Alberta? An example is the round-leaved sundew — a tiny carnivorous plant that can be found growing amongst the mossy hummocks in bogs and poor fens. Small insects are the typical prey attracted to the tiny white flowers of this plant. Its leaves are covered in tiny hairs coated in a sticky substance that traps mosquitoes, flies, and gnats, which provide the plant with necessary nutrients that are not available from the surrounding soil and water. When an insect lands on one of the hairs, their struggling triggers more of the surrounding hairs to bend towards the victim, holding it tighter. It can take up to 20 minutes for an insect to be fully trapped and up to a week to be fully digested. Once done, the hairs straighten out and wait for their next opportunity.

A wide range of wildlife species utilize peatlands for foraging, nesting, denning, and breeding. Whooping cranes, which are endangered, rely heavily on fens and bogs in northern Alberta for breeding habitat. Peatlands are also the primary habitat for woodland caribou in northern Alberta, another species at risk. Many other species of birds, mammals, and insects rely on peatlands for their needs.

Why Are Peatlands Important?

Wetlands are “natural infrastructure” that provide a variety of ecosystem services. Healthy plant communities in wetlands filter sediments out of flowing water. Bacteria, fungi, and wetland plants use nutrients for growth and break down contaminants into less harmful compounds. This cleans and purifies water that flows downstream in our rivers and into our lakes.

Wetlands also serve as large sponges across the landscape, catching water during runoff events that is slowly released over time. A landscape that is plentiful in wetlands will be resilient in years of drought as they slowly release water into the surrounding soils, supporting natural vegetation and crops.

Wetlands, and peatlands in particular, store more carbon per hectare than tropical forests. It is estimated that peatlands cover only 3% of the Earth’s surface, yet contain one-third of the Earth’s stored carbon!1 In our current world situation, where large amounts of carbon are released into the atmosphere from vehicles, the burning of coal and other fossil fuels, and industrial processes, it is extremely important that we protect our peatlands!

The Future of Peatlands

Unfortunately, peatlands in Alberta and around the world face many threats. Degradation of these wetlands occurs through climate change, drainage, conversion for agricultural purposes, burning, and mining of peat for fuel and soil amendments (peat moss for gardening).

Wetland drainage can have far-reaching effects on the surrounding environment. Disturbance of the hydrology and organic matter in peatlands can affect the stability of local temperatures and influence rain patterns. Think of how the temperature near the ocean in British Columbia is much more stable than the hot and cold temperature extremes experienced in the drier prairies. Releasing large amounts of carbon into the atmosphere also affects climate around the world.

While mineral wetlands are fairly resilient, peatlands are more difficult to replace or recreate. It has taken thousands of years for the peat in northern Alberta to accumulate.1 The best protection we can provide for this valuable resource is to prevent their disturbance and drainage in the first place.

References

- Ducks Unlimited Canada (2017). Boreal Wetlands and Climate Change. Available at https://abnawmp.ca/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/Boreal-Science-Summary-Final_web.pdf

Tina Mclean is an aquatic biologist who studied Environmental Science at Mount Royal University. She has a keen interest in wetlands, water quality, and watershed management.

Jay White is a professional biologist and owner of Aquality Environmental Consulting in Edmonton. He has been working in Alberta wetlands for the past 30 years.

Read the Original Article for this Post

For a richer reading experience, view this article in the professionally designed online magazine with all images and graphs in place.

This article originally ran in the Summer 2024 issue of Nature Alberta Magazine (Vol. 54 | No. 2).