Defending the Dark Sky

5 July 2024

BY GLEN HVENEGAARD

Most people have fond memories of the night sky. As a kid, I was proud to identify the Big Dipper for the first time, and then locate true north. As an adult, I was amazed at seeing Saturn’s rings through a telescope. Of course, seeing the Milky Way galaxy was truly awe-inspiring. Dark skies aren’t just inspirational, they’re important, for both wildlife and humans. In modern nights, our dark skies have been diminished, but there are actions we can take to protect them.

Many species of wildlife have evolved to rely on dark skies. For example, frogs and toads use darkness patterns to plan their nighttime breeding rituals. Many birds migrate or hunt at night, using natural light from the moon and stars. And many prey species require darkness for cover.

Humans also evolved with dark skies. Traditional night travellers depended on dark skies for navigation. The majestic night sky provided inspiration for many creation stories across cultures. Predictable patterns of darkness help maintain a healthy sleep schedule and human well-being.

Unfortunately, our dark skies are being diminished through light pollution: excessive or obtrusive artificial light caused by bad lighting design.1 There are several forms of light pollution:

- Glare includes lights that are excessively bright, such as some car headlights.

- Light trespass occurs when light shines beyond its intended target, such as streetlights that shine beyond streets into backyards or natural areas.

- Skyglow occurs when too much light shines into the atmosphere and is then reflected and scattered back to ground, making the night sky brighter.

The value of wasted energy from light pollution is estimated at $7 billion USD annually.1

All of this light pollution impacts wildlife and humans. Artificial light negatively affects the reproduction, predation, and migration of hundreds of wildlife species. Owls lose their hunting efficiency, hatchling sea turtles are less able to orient themselves to find the ocean, and insects cluster unnaturally around artificial lights. Light pollution also affects human health; artificial light at night can affect our natural circadian rhythms, disrupting our sleep patterns, which can lead to other health issues.

Light pollution also reduces opportunities for people to observe and appreciate the dark sky. Around the globe, about 23% of the land surface between the latitudes of 75°N and 60°S is exposed to some form of light pollution.2 As a result, up to 80% of the world’s population is unable to view dark sky features, such as stars, planets, auroras, meteors, and the Milky Way, our celestial home. Light pollution is projected to increase, and people are increasingly living in urban areas that have higher levels of light pollution. As a result, dark skies will become increasingly rare, and fewer people will be able to experience the grandeur of dark skies.

The good news is that many people, communities, and regions are seeking to reduce light pollution through management actions. This includes placing limits on light brightness, installing timers and sensors on lights, adjusting light hues, reducing the number of lights, creating shields to direct lights, and restricting the lights that people can use. Furthermore, land managers of many kinds are minimizing light pollution and promoting education about the night sky.

At the global level, the International Dark Sky Association (darksky.org) uses education, advocacy, retrofits, and community science to help protect the night sky. They designate international dark sky sanctuaries, dark sky reserves, dark sky parks (including the Waterton-Glacier International Peace Park), dark sky communities, and urban night sky places in order to raise awareness, identify threats, reduce light pollution, provide education, and promote authentic nighttime experiences.

At the national level, the Royal Astronomical Society of Canada has certified 26 dark sky sites, including dark sky preserves, nocturnal preserves, and urban star parks, with varying priorities and limits on artificial lighting (rasc.ca/lpa/dark-sky-site-program). Alberta is home to five dark sky preserves, at Beaver Hills, Cypress Hills, Lakeland, Jasper, and Wood Buffalo. There is also a nocturnal preserve at the Ann and Sandy Cross Conservation Area.

Dark sky initiatives also have the potential to stimulate rural economic development through tourism. This small but growing industry is supported by dark sky preserves, astronomical observatories and organizations, specialty tourism organizations, and dark sky festivals. It is difficult to estimate total participation, but a few examples will help. Yellowknife, NWT has claimed the title of “the aurora capital of the world,” with on average 240 potential nights per year to view this amazing phenomenon; in 2018, about 34,000 visitors spent $57 million. Dark sky tourists spend $500 million each year visiting the Colorado Plateau in the southwest U.S., stimulating creation of 10,000 jobs. Not surprisingly, dark sky tourists want to protect opportunities to view the night sky, and want more programs to help view the night sky.

In 2023, Alberta hosted at least 19 unique dark sky events, including festivals, celebrations, tours, astronomy programs at observatories, star parties, and sky-watching domes for rent. These events happen throughout the year.

The Jasper Dark Sky Preserve, at 11,228 km2, is the second largest in the world behind Wood Buffalo National Park. The Jasper preserve was designated in 2011 to minimize artificial light and educate the public and policy-makers about the importance of dark skies. The annual Jasper Dark Sky Festival is held over two to three weeks in October, a convenient shoulder season between busier summer camping and winter skiing periods, and with good night viewing conditions: longer nighttime hours, warm enough temperatures, and minimal cloud. The festival attracts a wide variety of visitors of all ages, expertise levels, and origins. The festival offers many free and for-purchase activities such as guest speakers, daytime and nighttime sky viewing through scopes, night hikes, and more. Among the many benefits, the festival has attracted up to 10,000 visitors per year, increased local economic impact, raised the profile of dark skies, and engaged the community in education and volunteerism.

The Beaver Hills Dark Sky Preserve (304 km2) was created in 2006, and includes Elk Island National Park, Miquelon Lake Provincial Park, Cooking Lake-Blackfoot Provincial Recreation Area, the Strathcona Wilderness Centre, and a Sherwood Park Fish and Game Association property. Many organizations offer dark sky events here. Miquelon regularly profiles the dark sky in its interpretive outdoor theatre program or guided hikes. Miquelon’s Hesje Observatory offers drop-in and bookable programs that include telescope viewing. Elk Island hosts a guided snowshoeing and stargazing excursion. Even spontaneous dark sky viewing is popular. For example, on some nights, after specialized apps and organizations announce the high likelihood of seeing auroras, Elk Island parking lots fill up at midnight — the nighttime traffic exceeding the daytime traffic!

Dark sky sites in their various forms help protect our dark skies by raising the profile of their value and providing opportunities to interact with the night sky in all its glory. Engagement encourages decision-makers to develop new policies to protect dark skies. I would encourage you to find a dark sky site in your area, venture out into the night, direct your gaze skyward, and reconnect with this wonderful aspect of our natural world.

References

- Gallaway, T., R.N. Olsen and D.M. Mitchell (2010). The economics of global light pollution. Ecological Economics, 69(3), 658–665.

- Falchi, F. et al. (2016). The new world atlas of artificial night sky brightness. Science Advances, 2(6)

Glen Hvenegaard is a Professor of Environmental Science at the University of Alberta, Augustana Campus. He and colleague Clark Banack are investigating how dark sky tourism can benefit rural communities and dark sky protection.

Read the Original Article for this Post

For a richer reading experience, view this article in the professionally designed online magazine with all images and graphs in place.

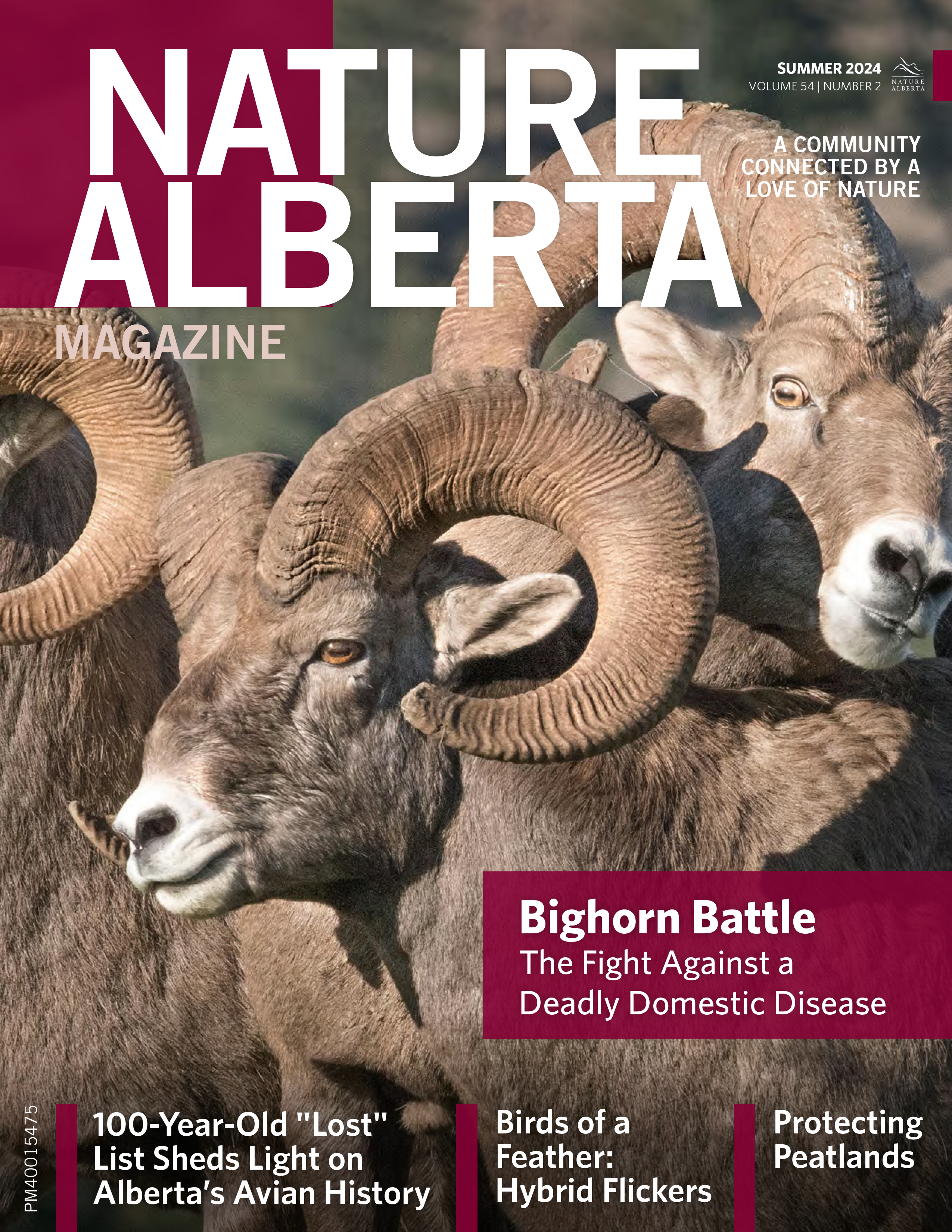

This article originally ran in the Summer 2024 issue of Nature Alberta Magazine (Vol. 54 | No. 2).