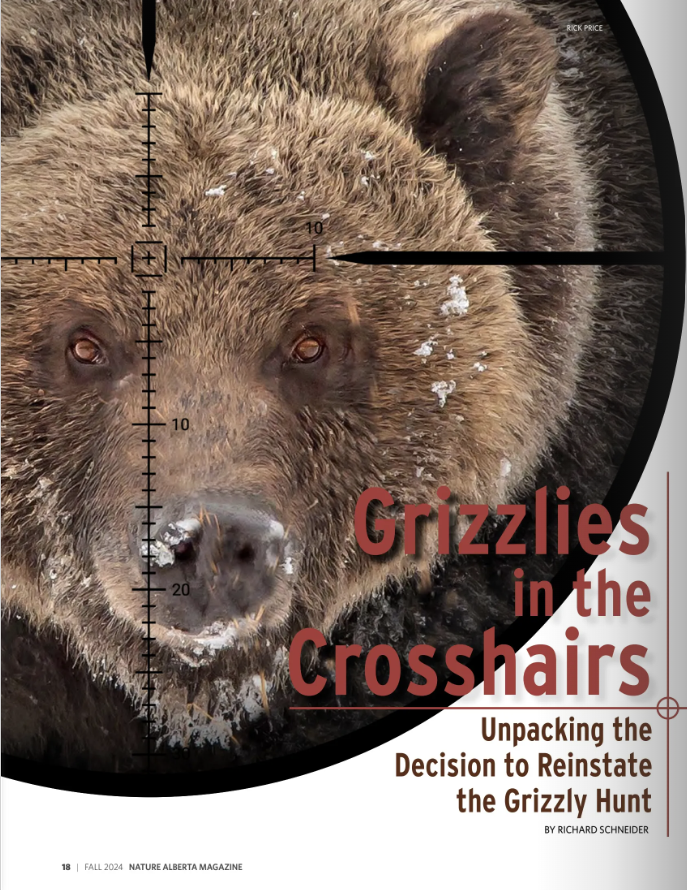

Grizzlies in the Crosshairs: Unpacking the Decision to Reinstate the Grizzly Hunt

18 October 2024

By RICHARD SCHNEIDER

The Alberta government’s recent decision to reinstitute a grizzly bear hunt is highly concerning from a conservation perspective. It’s also puzzling, since the idea seems to have come out of left field. Just four years ago, the province released a comprehensive grizzly bear recovery plan that outlined strategies for achieving a stable and sustainable grizzly population while also dealing with bear conflicts when they arise.1 This plan was the culmination of over six years of effort, involving workshops with experts and consultations with stakeholders and the public. Now, we are being told by the government that the province is being overrun with bears, and consequently a posse of hunters, selected through an online draw, is needed to protect the public from “grizzlies and other problem wildlife.”2 What’s going on?

To unravel these recent developments, we need to step back and examine the causes of the grizzly bear’s decline and the steps that have been taken to recover the population. Grizzly bears are one of the more challenging threatened species to manage because conservation is not the only goal. Managers also need to grapple with the dangers that bears can pose to humans and livestock. The recovery plan makes it very clear that continued public support for grizzly conservation is highly dependent on managing the risks that grizzlies pose. Last, but not least, outfitters and a subset of the hunting community continue to lobby for the reinstatement of a grizzly hunt.

Why Have Grizzly Bears Declined?

Before the days of European settlement, grizzly bears were found throughout most of what is now Alberta, including the southern prairies, where they lived alongside bison and other species of the open grasslands. As settlement brought farms, ranches, cities, and resource extraction, grizzly bears were extirpated from much of their original range. Today, the distribution of grizzlies in Alberta is restricted to the mountains and foothills.

Grizzly bears used to range across most of Alberta, but their core

habitat is now restricted to the Rocky Mountain region. RICK PRICE

Grizzly bear populations have continued to decline in recent decades, mainly because encounters with humans have led to an unsustainably high rate of mortality. Before the grizzly trophy hunt was halted, in 2006, hunting accounted for over 50% of human-caused grizzly deaths and was a major contributor to the population decline.1 The elimination of the hunt helped initially, but other sources of mortality have continued to be a problem. Based on the most recent data, the four highest sources of human-caused mortality now are poaching, accidental collisions with highway vehicles or trains, self-defence kills (usually by hunters), and black bear hunters misidentifying and shooting grizzly bears.

As with most conservation issues, there is also a habitat dimension to the problem. Much of the grizzly’s current range lies within the mountain park system, where the bears benefit from a high level of protection (though road and railway collisions remain a major problem). It’s a different story in the foothills, where parks only cover 1.4% of the region. Since the mid-20th century, the foothills have been subject to intensive development involving forestry, oil and gas extraction, and coal mining. Because of this industrial development, access roads now permeate the foothills. More recently, widespread off-road vehicle use has become a major additional source of disturbance. With a high level of access and activity comes a high level of bear encounters, and inevitable bear mortality.

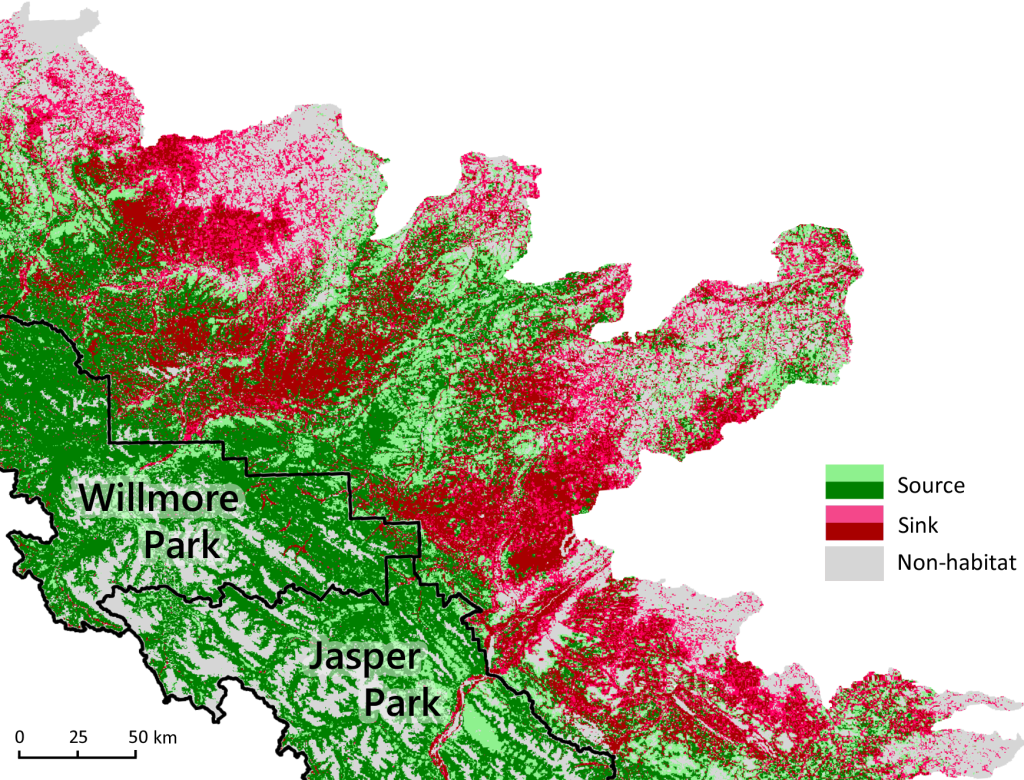

The relatively intact parts of the grizzly bear’s current range in Alberta are referred to as “source” habitat. In these areas, bear mortality and reproduction are relatively balanced, and the population is stable or even increasing. In contrast, areas that have experienced a high level of industrial development have an unsustainable rate of bear mortality. These areas are referred to as “sink” habitat, and the bear populations in these areas rely on the influx of dispersing bears from source habitat to remain viable.

The distribution of source and sink habitat for grizzly bears

along the eastern slopes of the Rocky Mountains in Alberta near

Jasper National Park. Sink habitats east of the mountain parks have

an unsustainably high rate of mortality associated with high levels

of human access. Adapted from Nielsen et al. 2006.3

Recovery Planning

Formal recovery planning for the Alberta grizzly bear began in the early 2000s, with a draft recovery plan completed in 2005.4 A key recommendation in this initial plan was to eliminate the grizzly hunt, and this was enacted in 2006. Additional recommendations included reducing conflicts between grizzlies and humans, reducing human-caused deaths, improving the scientific understanding of Alberta grizzly populations, and maintaining the integrity of grizzly bear habitat. In 2010, the grizzly was listed as a Threatened species under the provincial Wildlife Act.

The following decade featured intense field research on all aspects of the grizzly bear, including basic bear biology and habitat needs, causes and patterns of mortality, and mitigation options. There were also concerted efforts to better understand human-bear interactions and to identify the best methods for dealing with conflicts. These efforts culminated in the release of an updated grizzly recovery plan in 2020.1

The recovery plan divides bear habitat into three zones: Core, Support, and Habitat Linkage. The Core zone is where the province hopes to achieve and maintain a sustainable population of grizzly bears. A key recommendation is to limit road density within this zone to under 0.6 km/km2. Research has shown that the rate of bear mortality becomes unsustainable when road density exceeds this threshold.5 The Support zone provides an actively managed buffer that helps ensure the viability of the bear population in the Core zone. This buffer is needed because bears do not know where the boundaries of the Core zone lie, and so they often move between the Core zone and adjacent habitat. Without ongoing efforts to minimize human-bear conflict in the Support zone, the bear population in the Core zone would slowly be depleted. The role of the Habitat Linkage zone is to maintain connectivity between habitat zones, which is critical for maintaining gene flow.

Many of Alberta’s grizzly bears reside in the foothills region, which has been heavily impacted by industrial development. The mortality rate of

bears in this region is unsustainably high. RICK PRICE

Another key strategy in the recovery plan is to increase public support for grizzly bear conservation, especially among those living, working, and recreating in bear habitat. Researchers have found that residents and workers in bear country generally (but not exclusively) have positive attitudes to grizzly bears. However, it is important to provide these individuals with the opportunity to participate in local management solutions in order to maintain their support. Promptly dealing with problem bears, either through translocation (where feasible) or euthanasia, is also important, as is providing compensation for economic losses attributable to bears.

Other elements of the recovery plan include education and outreach (delivered through the BearSmart program), managing food attractants that draw bears to human settlements and agricultural areas, reducing accidents that result in bear mortality, minimizing the illegal killing of grizzlies, and ongoing monitoring and research.

Ministerial Monkey Wrench

Given the years of effort and the extensive consultation that went into the 2020 grizzly recovery plan, this new policy that enlists hunters to control grizzly bears — enacted by ministerial order without input or support from wildlife biologists, relevant scientific data, public consultation, or proper legislative review — is both puzzling and concerning. The pieces just don’t add up.

Let’s begin with the rationale given for the policy change. In his press release, Minister Loewen said, “As Alberta’s grizzly bear and elk populations continue to grow in numbers and expand their territories, negative interactions have increased in both severity and frequency.”2 The impression we are given is that the province is suddenly overrun by bears, necessitating urgent and extraordinary control efforts. The reality is that we do not have a good estimate of current grizzly population numbers, mainly because the bears exist at low densities across vast areas, making them difficult to census. According to the best available data, published in the 2020 recovery plan, there has been growth in a couple of localized areas, but no indication that the entire grizzly population is rapidly expanding. The rationale for changing the Wildlife Act and overriding the grizzly recovery plan appears to be contrived.

Next, where did the idea to enlist hunters come from? It’s definitely not part of the bear management toolkit that has been developed through years of research and field testing, both in Alberta and around the world. We know what works: electric fencing, attractant management, acoustic and visual deterrents, livestock guardian dogs, bear spray for individual protection, education and outreach, and collaborative management at the local level. When prevention falls short, bear relocation can be used to address local problems without negatively impacting the bear population.

In some cases, problem bears do need to be killed, especially repeat offenders and bears exhibiting dangerous behaviour. Until now, this has been done by trained fish and wildlife officers. Transferring this task to private citizens with no ties to the grizzly bear recovery program is not wildlife management. It is simply bear hunting in disguise.

The inescapable conclusion is that the government's claim about instituting a new policy to protect the public is a ruse. If he was serious about managing bear conflicts, he would be directing more resources to implementing the conflict mitigation measures in the 2020 grizzly recovery plan. In particular, there is much more that should be done in terms of expanding the BearSmart program, improving landowner compensation, and advancing local-level management planning. We should also be filling the Human-Wildlife Conflict Specialist staff position, which has been vacant for the past couple of years. As for killing problem bears, fish and wildlife officers are more than capable of handling this task without the aid of hunters, as they have for decades. We are left to speculate as to the real reason for the new policy, but the cui bono (who benefits) rule suggests that lobby efforts by outfitters and grizzly hunters are likely involved.

We Need to Do Better

The deeper problem here is bad decision-making, on at least two levels. Minister Loewen has done an end-run around his own government’s planning process for grizzly bears. Planning provides a structured process for obtaining public input, clarifying objectives, identifying trade-offs, and applying science to craft workable solutions. Informed by this process, elected officials sometimes have to make difficult political decisions about intractable trade-offs. But this is not the same as crafting policy by winging it, which is what this ministerial order has done.

We also see here the prioritization of special interests — outfitters and grizzly hunters — over the broad public interest. Most Albertans place a priority on grizzly bear recovery rather than reinstituting grizzly bear trophy hunting. It’s likely this applies to the general hunting community as well, as most hunters are conservation oriented. Indeed, hunting groups like Ducks Unlimited have been instrumental in advancing conservation in Alberta and other parts of Canada.

Grizzly bears are a keystone species; they serve as an important

indicator of ecosystem health. It is vital that they remain protected.

RICK PRICE

Unfortunately, the decision to revive the grizzly hunt seems to be part of a general deterioration in natural resource decision-making by the current government. The list of decisions favouring special interests has been growing, sidelining the work of professional wildlife managers and the interests of the general public. For example, we have seen the same type of political intervention occur with the hunting of cougars, which is now permissible within some provincial parks.

If these developments are of concern to you, please take a few minutes to write to Minister of Forestry and Parks Todd Loewen and let him know your views: fp.minister@gov.ab.ca. Be sure to cc your local MLA as well. A letter template is available at naturealberta.ca/grizzly-hunt-action, which you can use as-is or modify. As we have seen in the past, change is possible if enough concerned citizens push back and demand more of their government.

References

- Alberta Environment and Parks (2020). Alberta Grizzly Bear Recovery Plan. Alberta Species at Risk Recovery Plan No. 37. Edmonton, AB.

- Alberta Government. July 9, 2024 News Release. Available at: https://www.alberta.ca/release.cfm?xID=90627FA92D516-F852-9BAF-A462F6C3D44224AC

- Nielsen, S., G. Stenhouse and M. Boyce (2006). A habitat-based framework for grizzly bear conservation in Alberta. Biological Conservation 1230:217-229.

- Alberta Sustainable Resource Development (2008). Alberta Grizzly Bear Recovery Plan 2008-2013. Alberta Species at Risk Recovery Plan No. 15. Edmonton, AB.

- Proctor, M. et al. (2019). Effects of roads and motorized human access on grizzly bear populations in British Columbia and Alberta, Canada. Ursus 30: e2.

Richard Schneider is a conservation biologist who has

worked on species at risk and land-use planning in Alberta

for the past 30 years.

Read the Original Article for this Post

For a richer reading experience, view this article in the professionally designed online magazine with all images and graphs in place.

This article originally ran in the Fall 2024 issue of Nature Alberta Magazine (Vol. 54 | No. 3).