Lake Sturgeon – From the Depths of Time

5 July 2024

BY LORNE FITCH

A monster prowls the depths of Alberta’s prairie rivers. Not a malevolent one, but one of leviathan size and ancient origins. If you want to talk about big, old fish, you need look no further than lake sturgeon. While these fish are indeed lake dwelling, including the Great Lakes, in Alberta they are only found in rivers.

Lake sturgeon have been swimming the waters of North America for about 136 million years. They swam while dinosaurs roamed, and then watched those “terrible lizards” disappear. If they had kept diaries, they could have recorded the mountain building, multiple glaciation events, and finally the erosion that created the landscapes of Alberta, including the river courses of their current residence. Only on the last page, maybe the last line, would there be a record of people appearing.

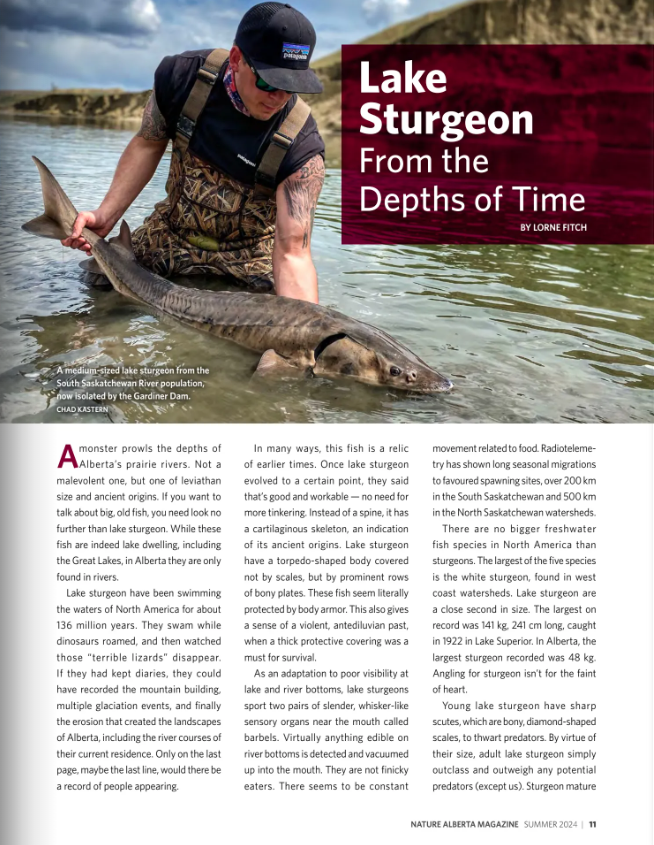

In many ways, this fish is a relic of earlier times. Once lake sturgeon evolved to a certain point, they said that’s good and workable — no need for more tinkering. Instead of a spine, it has a cartilaginous skeleton, an indication of its ancient origins. Lake sturgeon have a torpedo-shaped body covered not by scales, but prominent rows of bony plates. These fish seem literally protected by body armor. This also gives a sense of a violent, antediluvian past, when a thick protective covering was a must for survival.

As an adaptation to poor visibility at lake and river bottoms, lake sturgeons sport two pairs of slender, whisker-like sensory organs near the mouth called barbels. Virtually anything edible on river bottoms is detected and vacuumed up into the mouth. They are not finicky eaters. There seems to be constant movement related to food. Radiotelemetry has shown long seasonal migrations to favoured spawning sites, over 200 km in the South Saskatchewan and 500 km in the North Saskatchewan watersheds.

There are no bigger freshwater fish species in North America than sturgeons. The largest of the five species is the white sturgeon, found in west coast watersheds. Lake sturgeon are a close second in size. The largest on record was 141 kg, 241 cm long, caught in 1922 in Lake Superior. In Alberta, the largest sturgeon recorded was 48 kg. Angling for sturgeon isn’t for the faint of heart.

Young lake sturgeon have sharp scutes, which are bony, diamond-shaped scales, to thwart predators. By virtue of their size, adult lake sturgeon simply outclass and outweigh any potential predators (except us). Sturgeon mature even later than humans — 15 to 20 years for males and 20 to 25 for females. (I should point out this is sexual maturity, since tangible evidence of other forms of maturity is still lacking in humans at this age.) They can outlive us, with records of specimens up to 150 years old; the oldest recorded in Alberta was 62.

In a way, their body form and their ecology have served lake sturgeon well, from their origins in the primordial soup of a tropical Cretaceous world, through several ice ages, and into modern times. It’s actually these modern times that severely test them. In Alberta, the population is now truncated into two, one in the North Saskatchewan River, the other in the South Saskatchewan. Gardiner Dam on the South Saskatchewan River divides and isolates one population from the other. The E.B. Campbell Dam in eastern Saskatchewan isolates the North Saskatchewan population from downstream ones.

In Alberta, lake sturgeon historically swam in the Oldman River up to the confluence with the Castle River, in the Bow River up to near Bassano, up the Red Deer River to the confluence with the Medicine River, and throughout the South Saskatchewan River. They were common in the North Saskatchewan River upstream to Drayton Valley. Strangely, the only record of them in the Sturgeon River is the harvest of 682 kilograms over the winter of 1916–1917. At one time the oil rendered from sturgeon was used to fuel lamps. Hopefully we are more enlightened now about the value of sturgeon!

Although the population has inched up from critically low numbers of the past century, which precipitated an angling closure from 1940 to 1968, they are by no means abundant today. Currently, the province’s fish sustainability index ranks sturgeon as “low” in the South Saskatchewan; “very low” in the Oldman, Bow, Red Deer, and North Saskatchewan rivers; and functionally extirpated in the upper portions of the Oldman and Red Deer rivers.

Not surprisingly, lake sturgeon are ranked as Threatened in Alberta and Endangered federally by the Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada (COSEWIC). The viability of lake sturgeon remains at risk, for a variety of reasons.

Very few people have ever seen a live lake sturgeon or, for that matter, realize they exist in our prairie rivers. Sequestered in pools several metres deep, with water opaque with sediment, so much so your hand disappears from view only a few centimetres into the water, sturgeon are not part of routine fish watching. Angling for them would test the patience of Job. Moreover, because of their “at risk” status, fishing for sturgeon is strictly catch and release.

To be protected, a critter first has to be acknowledged, which is a challenge for biologists in an ecologically ignorant world. Biologically, any species that takes a long time to mature is at risk (except, it seems, us humans), since the Grim Reaper has a lengthy time period to exercise his scythe before reproduction occurs. Isolating the Alberta population into two separate groups hampers the genetic exchange and movement necessary to bolster population sizes. Declines in water quality and quantity have influenced, and will continue to have an effect on, the ability of lake sturgeon to move, spawn, rear, feed, and overwinter. The more pressure we put on prairie rivers to meet our needs, the less able they are to provide for sturgeon.

As climate change results in hydrologic shifts — less river flow, more variability in flow, and greater flood frequency — we respond with more water diversions, especially for irrigation agriculture. Not only is there less remaining water to keep rivers healthy, we have also built dams and diversions —like Bassano Dam, Dickson Dam, and the Lethbridge Weir — that block upstream movement.

New dams on the South Saskatchewan River (Meridian Dam) and lower Bow River, plus new diversions from the lower Red Deer River (Special Areas Water Supply Project) have been proposed. In Saskatchewan there is a proposal for a dam on the North Saskatchewan River near North Battleford (Highgate Dam). If built, these would further fragment sturgeon populations, putting the Alberta population at even greater risk.

The Alberta Lake Sturgeon Recovery Team laid out a rather frank appraisal of key concerns and issues in the Alberta Lake Sturgeon Recovery Plan 2011–2016. In so many words, perhaps not couched as bluntly, their advice for retaining and allowing the recovery of lake sturgeon populations included: 1) stop over-allocating water, which exacerbates many other issues for the species; 2) don’t build any more dams or diversions that impede movement; 3) clean up the water in our rivers; and 4) deal with some of the unanswered questions about sturgeon biology and ecology.

Terry Clayton, retired provincial fisheries biologist and chair of the Sturgeon Recovery Team, stated, “I worry most about the increasing water demands, especially for irrigation in the south and the cumulative effect on water quality of urban and industrial development in the North Saskatchewan. Failure to address these issues will undermine recovery efforts and our ability to retain viable sturgeon populations.” Serious commitment to recovery would start with the government setting and adhering to ecologically relevant river flow that puts water back into rivers and keeps it there.

Lake sturgeon remind us of the past, a past of deep time, a fossilized past. That they have endured so much, for so long, should fill us with admiration for their persistence. Instead, we have whittled down their opportunities to survive into the future, out of neglect, ignorance, and to a degree, greed.

If we saw sturgeon differently, not as impediments to further development but as a testament to healthy, intact rivers, we might be inclined to treat them and the rivers they exist in better. There is a reality we consistently ignore: Even though lake sturgeon have been on the path longer, it is the same path as ours.

Lorne Fitch is a Professional Biologist, a retired Fish and Wildlife Biologist and a former Adjunct Professor with the University of Calgary.

Read the Original Article for this Post

For a richer reading experience, view this article in the professionally designed online magazine with all images and graphs in place.

This article originally ran in the Summer 2024 issue of Nature Alberta Magazine (Vol. 54 | No. 2).