A Nod to the Long-tailed Weasel

16 April 2025

By MYRNA PEARMAN

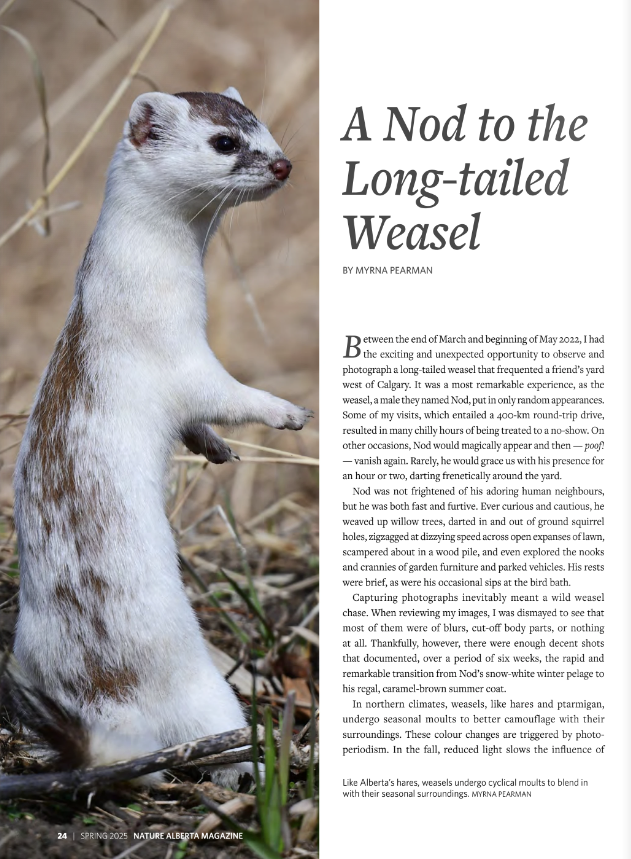

Between the end of March and beginning of May 2022, I had the exciting and unexpected opportunity to observe and photograph a long-tailed weasel that frequented a friend’s yard west of Calgary. It was a most remarkable experience, as the weasel, a male they named Nod, put in only random appearances. Some of my visits, which entailed a 400-km round-trip drive, resulted in many chilly hours of being treated to a no-show. On other occasions, Nod would magically appear and then — poof! — vanish again. Rarely, he would grace us with his presence for an hour or two, darting frenetically around the yard.

Nod was not frightened of his adoring human neighbours, but he was both fast and furtive. Ever curious and cautious, he weaved up willow trees, darted in and out of ground squirrel holes, zigzagged at dizzying speed across open expanses of lawn, scampered about in a wood pile, and even explored the nooks and crannies of garden furniture and parked vehicles. His rests were brief, as were his occasional sips at the bird bath.

Capturing photographs inevitably meant a wild weasel chase. When reviewing my images, I was dismayed to see that most of them were of blurs, cut-off body parts, or nothing at all. Thankfully, however, there were enough decent shots that documented, over a period of six weeks, the rapid and remarkable transition from Nod’s snow-white winter pelage to his regal, caramel-brown summer coat.

In northern climates, weasels, like hares and ptarmigan, undergo seasonal moults to better camouflage with their surroundings. These colour changes are triggered by photoperiodism. In the fall, reduced light slows the influence of melanocyte-stimulating hormone (MSH), which in turn reduces the production of melanin, a pigment produced by specialized melanocyte cells found in the hair follicle. It is thought that an inhibitor either prevents the pituitary gland from producing MSH or prevents the follicles from responding to it. Come spring, the opposite process occurs. In addition to affording camouflage, it is thought that their white winter pelage might provide some thermoregulatory advantage, since white hair has air, not pigment, trapped within its structure. White hair, which is also thinner, may also be denser and thus warmer.

The long-tailed weasel’s winter pelage may help keep it warm as the

white hair has air, not pigment, trapped within its structure. MYRNA PEARMAN

There are three species of weasels in Alberta: the long-tailed, short-tailed, and least weasel. All are ferocious carnivores. Streamlined in shape, they are thin, remarkably flexible, and move at astonishing speeds. Dependent on maintaining their svelte bodies to easily enter small holes and burrows in pursuit of prey, they do not, like other northern mammals, put on an insulating layer of fat. Not only must they compensate for this lack of fat, but their high metabolic rates, sustained high levels of activity, and large surface area to body volume (which results in excess heat loss) mean that they must consume large quantities of food each day. And, since they have relatively small stomachs, they must eat often; it is estimated that they consume about one third of their body weight every 24 hours. Excess food is sometimes cached and then accessed up to months later, thanks to their excellent olfactory abilities and impressive spatial memories. During the spring and summer, weasels consume eggs, nestlings, and small mammals. During the winter, mice, voles, and red squirrels become their main prey items. Interestingly, weasels will sometimes usurp the burrows of their prey and will even line their new homes with their victims’ skins. Nod didn’t capture any prey while I was observing him, but other observers often saw him race around with dead voles and mice in his jaws.

Out in the winter woods, the characteristic two-by-two footprints make weasel tracks easy to identify. I have often followed the meandering trail of a weasel in the snow, just to see where it leads. It sometimes ends at a small hole where the weasel has darted down through the snowpack to terrorize the mice and voles that remain active all winter in the pukak layer, the interface between the ground and the snow.

Long-tailed weasels have an interesting reproductive strategy. Sexes are solitary for most of the year, but when breeding season arrives, males must locate the females. Their male parts also enlarge at this time, a process we observed with Nod. Males will often travel long distances, using their keen sense of smell to follow the odour of female urine. Females come into estrous once a year, and then only for three to four days. Mating, which induces ovulation, is aggressive and can take up to four hours. The eggs, once fertilized, pass down the fallopian tubes to the uterus. They divide into a blastocyst that, due to low levels of progesterone, floats within the uterus for up to nine months. As the daylight hours lengthen in the spring, progesterone levels increase, causing the blastocyst to implant. This process of delayed implantation ensures that the young are born in the late spring/early summer, when food is plentiful.

The remarkable transition from snow-white winter pelage to caramel-

brown summer pelage takes about six weeks. MYRNA PEARMAN

While my friends were fortunate to also observe both a female and another male weasel in their yard, I was grateful to have witnessed and photographed Nod over the course of his remarkable transformation.

Myrna Pearman is a retired biologist as well as a best-selling author, enthusiastic nature photographer and writer, kayaker, and backroads rambler.

Read the Original Article for this Post

For a richer reading experience, view this article in the professionally designed online magazine with all images and graphs in place.

This article originally ran in the Spring 2025 issue of Nature Alberta Magazine (Vol. 55 | No. 1).