The Ancient Ritual: Wolves and Bison in Wood Buffalo National Park

11 February 2025

By LU CARBYN

In my 31-year career as a biologist and research scientist with the Canadian Wildlife Service, I had the good fortune to work on wolf-prey systems in Canada and other parts of the world. Some of my most memorable experiences were within Wood Buffalo National Park (WBNP), a huge boreal forest environment with a generally flat topography, interspersed with glacially formed eskers, within a major landlocked delta system (the Peace-Athabasca Delta, which has an area of approximately 5,000 km2). During an official seven-year study, alongside students and wardens, we captured and collared 43 wolves (tracking them from the air). I continued on-ground observational research independently for an additional 14 years, following bison herds in the delta to document wolf-bison interactions.

I was spending weeks at a time in the delta, following bison herds to watch wolves preying on them. I relished the solitude of hiking along a ribbon of water bearing the unlikely name of Lousy Creek. My nearest human neighbours were in Fort Chipewyan, a hamlet six hours away by low-powered motorboat, or two days by canoe!

One particularly momentous mid-October morning, I left my tent early and went exploring on a trail that led to my favourite lookout. As the sun’s rays began to penetrate the mist, I could make out a herd of bison — 30 of them, mostly lying down. Scanning the area with my binoculars, I spotted more bison in the distance. A faint long line of black, possibly 200 bison, were coming to join this smaller herd. Then I noticed a shorter, white line moving briskly towards the herd — wolves!

The wolf-bison predator-prey dynamic is unique to WBNP, an ancient and dramatic struggle between Earth’s largest canid species and the largest land mammal in North America. STEPHANIE WEIZENBACH

The bison began to run, and the wolves picked up their pace. As they closed in, the black line split in two. Calves, the prime targets for wolves, usually move to the centre of the herd when wolves are in pursuit. The wolves had succeeded in exposing the calves. The black and white streaks intermingled. The smaller herd closer to me seemed oblivious to the drama unfolding in the background for a few minutes, until they too became embroiled in the melee.

With wolves pressing hard, the large herd stampeded in my direction. First came the lead cow, thundering at full speed, with the rest following. Then, dashing in and out, came the wolves. Except for the muffled rumble of hooves, predator and prey were so eerily silent that it all seemed surrealistically mechanical. I saw wolves attempting to tear at the hindquarters of bison, bison wheeling about to face the wolves and then running again in panic. I could feel my heart pounding in my throat. The closer the action, the more engrossed I became. There was no escape, no cover if I were to be surrounded. Nothing to do but watch and wait!

The wolves had isolated a large calf. Within minutes they were slashing and tearing at its hind end. In their frenzy, they also attacked its front and middle. Most of the adult bison moved on, but three cows made a vain attempt at rescue. They soon left as well. It seemed the calf’s fate was sealed. The wolves and calf formed a single, moving mass. As the calf’s stomach was ripped open, the heat of the body cavity mingled with the cold air around it, forming a halo of condensation around the wolves and calf. That image was burned into my mind — both the beauty and the cruelty of the sight. A large wolf braced its hind legs firmly on the ground and clawed itself onto the calf, gripping its back with its teeth. Suddenly, the action stopped. The wolves quickly slunk off, abandoning the injured calf, which now lay hunched. I was perplexed, until I was finally able to hear what the wolves’ sharper ears already had: motorboats. Every fall and spring, Indigenous hunters from Fort Chipewyan motor up and down rivers and creeks, shooting ducks and geese.

The wolves dispersed over the meadow, some lying down, others moving about restlessly, but unwilling to finish off the wounded calf. One wolf was licking blood from its front paw, the white fur around its muzzle smeared red. I could count the wolves: 17, all light in color. After some time, four returned to the injured calf, which lay exhausted, abandoned by the herd. The foursome grabbed at the victim, which once more stood to defend itself. But the four attackers moved off again as the drone of the motorboat continued to threaten.

The herd returned and a single cow deliberately and rapidly advanced and sniffed the calf. Then the most heartrending sight unfolded. The mortally wounded calf began to follow the cow. It could only move very slowly, head bent to the ground. A few remaining wolves watched from a distance as the cow and calf moved off into the aspen forest.

I sat in a daze. How tough and stoic the calf was. I tried to master my feelings of pity. I wanted to end its misery, but in a national park, nature must be allowed to run its course unimpeded.

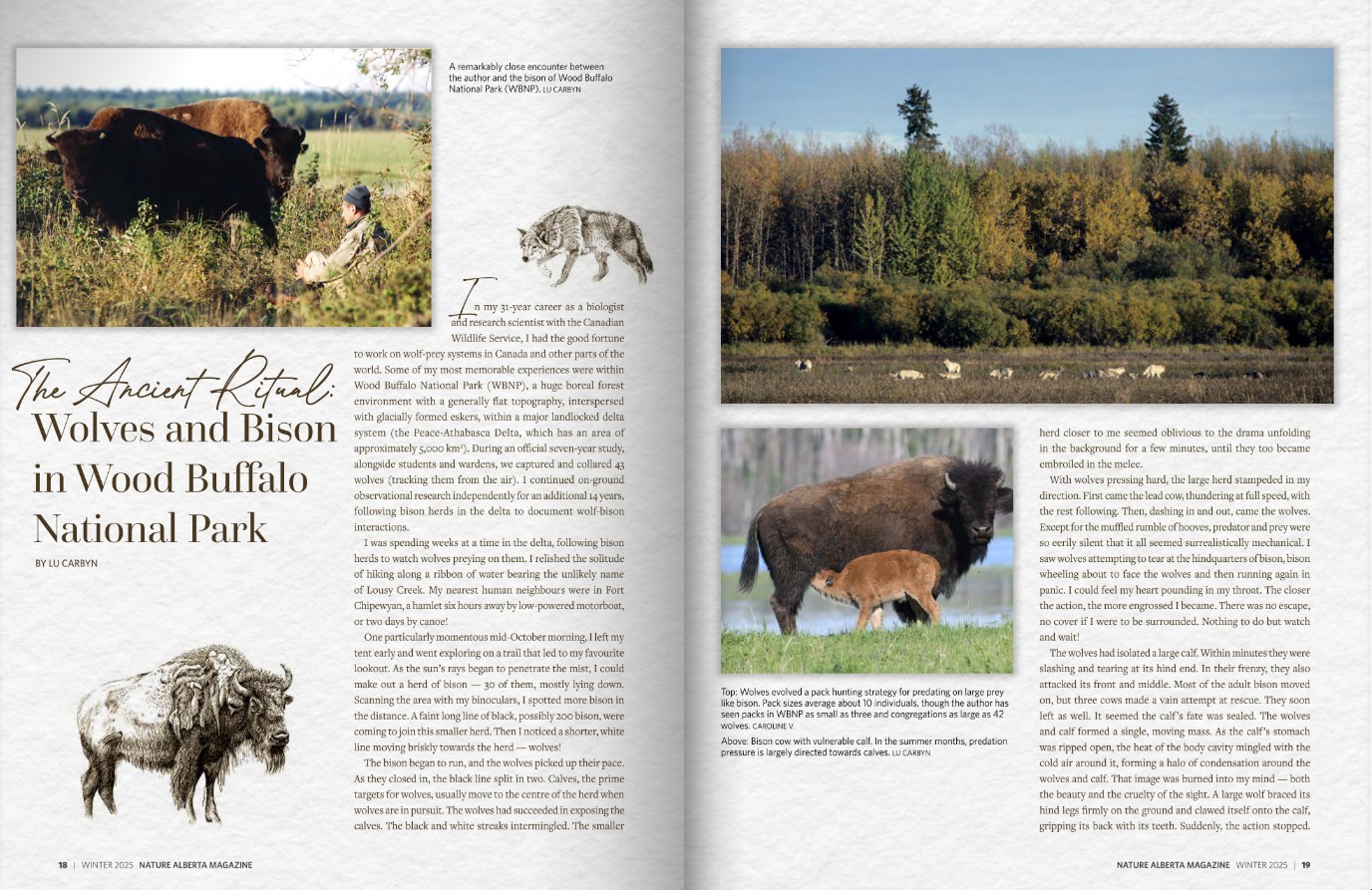

Bison cow with vulnerable calf. In the summer months, predation pressure is largely directed towards calves. LU CARBYN

This codependent wolf-bison relationship is unique to WBNP. Nowhere else do wolves prey primarily on bison; only incidentally. In other multi-predator-and-prey systems, such as Yellowstone and Banff National Parks, wolves are far less likely to prey on bison because smaller hooved mammals, such as elk and deer, are abundant and easier to kill. Wolves prey primarily on hooved prey animals, with rare exceptions, such as along Canada’s west coast, where wolf packs exclusively feed on salmon during the spawning season. WBNP does not have any substantial populations of deer species; therefore, wolves must rely on wood bison for prey. This predator-prey dynamic is doubly unique for also being between the largest canid on Earth and the largest land mammal on the continent.

The “buffalo wolf” is an apex predator that has evolved a strategy for hunting bison. Though efficient predators, it is a very difficult task for wolves to kill a prey species as large as bison. Consider the odds: wood bison can weigh up to 1,200 kg and wolves average 45 kg. Wolves bring down this large prey by using their dagger-like canine teeth to slash and maim an intended victim on the run. Wolves have strong jaw muscles and once clenched, exert severe bite pressures — among the strongest in the animal kingdom. The wolf’s muscular body, long legs, and physiology allow wolf packs to travel over large areas to track and run down prey. An individual wolf can maintain a steady trot of about 8 km/h, resulting in long-distance movements recorded as far as from northern Canada to the western United States. Such movements, however, render the species vulnerable to human-caused mortality. The top running speed of a wolf is around 60 km/h, while that of bison is around 45 km/h. It would seem at first consideration that, based on speed alone, it would be easy for a wolf to outrun, slash, and kill its victim. But that is not the case. Bison have thick hides, deadly horns and, above all, are persistent and agile in defending themselves. Wolves cooperatively hunt in packs, making it possible for them to kill a bison, although I have witnessed incidents where a single wolf was able to kill an adult bison that was in a very weak state. Wolves are known for their social pack structure. Pack sizes can be as small as three wolves but usually average about 10 individuals. In WBNP, I have encountered aggregations of as many as 42 wolves on a single lake near large bison herds. I was not sure whether these represented large single packs or several packs that had given up on territorial strife to access a limited food supply.

Observations in WBNP have shown bison staying in proximity of wolves for hours on end without much in the way of visible signs of fear or agitation. Once wolves show intent of predation, bison behaviour can quickly change from tolerance to alarm. Initially, adult bison may act with aggressive defensive behaviour, particularly to protect wounded or even dead calves. Bison defences can seriously injure wolves. Ultimately, bison will adopt a flight response. Attack by wolves places a constant pressure on movements by bison in their home ranges. One such displacement recorded one herd moving 82 km within a 24-hour period.1

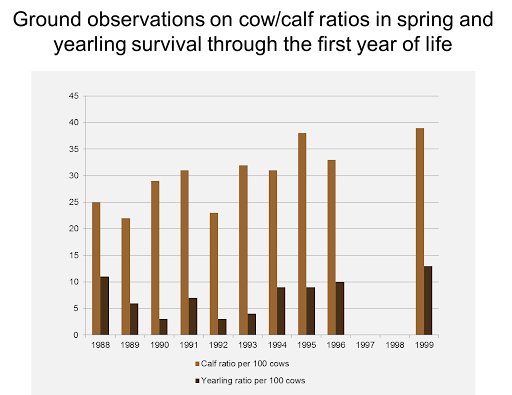

An important part of my research in WBNP was conducting cow-calf counts to determine the number of calves born in spring and what percentage survived the first year and got recruited into the herd the following year. My study at the time had shown that predation pressure in summer is largely directed towards bison calves.2,3 Ground observation on calves born in spring was about 30 calves per 100 cows. These are well below maximum potential birth rates in bison, as determined from calf production seen in captive animals on game ranches. Wolves live in a world of feast or famine. Individuals have been known to survive for several weeks without much, if any, food intake. However, when available, 3.5 kg of meat per wolf per day is optimal for survival. After making a fresh kill, a single wolf can consume 15–20% of its own body weight. I have had close encounters with wolves after such events and saw their bellies swaying back and forth as they tried to run away. In winter, there was a marked shift of predation to all age and sex classes.3 Survival of calves to the yearling stage in WBNP was so low that it was undoubtedly a significant factor in the decline of bison numbers in WBNP. Much of that was because of wolf predation.

Which brings us back to the tragic fate of our calf. Nature can seem cruel, but it forces the dynamics of change, driving ecosystems to adjust and evolve. Without the wolves, the bison would populate beyond the capacity of the park; without the bison, the wolves would not have a sustainable food source. Hard as it is to watch, death is the companion of life, and the natural cycle continues in WBNP. After all that wolves and bison have endured in the past couple of centuries, we are fortunate to still be able to witness this ancient ritual of death and survival in the wilds of our province.

References

- Carbyn, L.N. (1997). Unusual movement by bison, Bison bison, in response to wolf, Canis lupus, predation. Canadian Field Naturalist, 111(3):461-462.

- Carbyn, L.N. and T. Trottier (1987). Responses of bison on their calving grounds to predation by wolves in Wood Buffalo National Park. Canadian Journal of Zoology, 65(8): 2072-2078.

- Carbyn, L.N., S.M. Oosenbrug and D.W. Anions (1993). Wolves, Bison and the Dynamics Related to the Peace-Athabasca Delta in Canada’s Wood Buffalo National Park. Circumpolar Research Institute. University of Alberta, Edmonton.

Lu Carbyn is an adjunct professor at the University of Alberta, a retired Canadian Wildlife Service biologist, and a Provincial Regional Representative of Nature Alberta.

Read the Original Article for this Post

For a richer reading experience, view this article in the professionally designed online magazine with all images and graphs in place.

This article originally ran in the Winter 2025 issue of Nature Alberta Magazine (Vol. 54 | No. 4).