Bloodsucking Leeches: More Than Just a Horror Icon

Leeches are capable swimmers and can move quickly to find a suitable surface to hide on, including hip waders, making for easy specimen collection. CHRISTIAN FISCHER

BY CHERYL TEBBY

There are not many creatures in the animal kingdom that invoke more immediate feelings of revulsion and abhorrence than leeches. Squishy and cold, emerging from the watery depths to feed on warm blood… It’s understandable why leeches may inspire nightmares.

Popular depictions of leeches often include concentric rows of sharp, fang-like teeth, or maybe an elongate ventral sucker that enables them to cling to their victim like the sticky-hand toys found in birthday “goody bags.” But in real life, leeches are a little more prosaic, much less horror-movie monster.

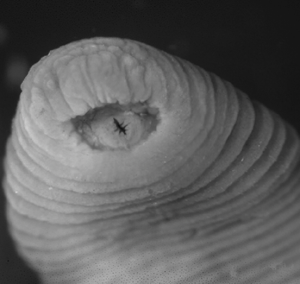

A closeup view of a leech sucker. ANNA PHILLIPS

Leeches belong to the phylum Annelida, the segmented worms, and are in the same taxonomic class as earthworms. Their most notable features are their two suckers. The front sucker may have calcified “teeth” for feeding, whereas the rear sucker functions only as a suction-cup for grip. Oftentimes both suckers are used for locomotion on a solid surface, creating a movement pattern like that of an inchworm. In open water, leeches are graceful swimmers and can be spotted swimming in an undulating motion. In terms of appearance, leeches are usually dully colored but can sport attractive spots and stripes. They have simplistic eyes in multiple pairs or rows.

An Undeserved Reputation

Despite their negative reputation, leeches have done much for humankind. For instance, species of the blood-feeding genus Hirudo were used for centuries for bloodletting in efforts to cure a number of illnesses. Leeches were perfect for this popular medical procedure because their saliva contains multiple proteins that increase blood flow and also prevent blood clotting. Additionally, leech saliva contains an anesthetic, making their bite painless. Bloodletting is no longer considered to be an effective cure-all; however, leeches still have a place in modern medicine because of their ability to stimulate circulation. In particular, leeches are used after microsurgeries such as digit reattachment or tissue transplants to restore blood flow to targeted areas.

Wetlands like this are prime habitat for leeches. CHRISTIAN FISCHER

Leeches are also useful for environmental monitoring. The gut of a leech contains the DNA of fauna in the surrounding area, allowing scientists to track the presence and absence of rare or endangered animals as well as the presence or absence of invasive species.1 What makes them especially useful for this purpose is their ease of collection — if they aren’t plucked off of submerged rocks and vegetation, they’re stuck on the collector themselves!

Leeches in Alberta

In Alberta, there are four families of leeches. Only one of these families, the Hirudinidae, contains true biting leeches, and within this family, only one species is known to regularly bite and take a blood meal from humans. This is Macrobdella decora, commonly called the North American medicinal leech. It possesses muscular ridges or “jaws” in their anterior sucker that allow them to bite their warm-blooded host. It is worth noting that other leech species may opportunistically feed on open wounds or thin or damaged skin if given time to attach.

A medicinal leech, the only leech in Alberta known to regularly bite humans. CLAUDIE B

Members of the Piscicolidae family are seldom seen by anyone but anglers, as they exclusively parasitize fishes. They are perhaps the most distinctive of Alberta’s leeches, as their flattened, circular anterior sucker stands out from their cylindrical body.

Lastly, the Glossiphoniidae and Erpobdellidae families include the leeches you are most likely to scoop up in samples from shallow water bodies. They prey mainly on smaller aquatic invertebrates, which they swallow whole. They are not particularly selective in what they eat — small crustaceans, worms, and fly larvae are all fair game. All species of glossiphoniids possess a piercing proboscis rather than jaws, allowing them to tackle larger invertebrates and to parasitize larger aquatic animals, including turtles and waterfowl. For example, Theromyzon species (otherwise known as “duck leeches”) attach to the eyes and nasal passages of ducks and swans, and in large numbers may even cause the fatality of trumpeter swan cygnets.2 These leeches, when attached to people, are not feeding but instead are mistaking the cool smooth skin of swimmers and waders as submerged rock or wood to rest on.

A duck leech, which parasitizes various waterfowl species. JOE HOLT

If you are unlucky enough to have been found by a hungry medicinal leech, then the easiest course of action is to just let them finish feeding, whereby they will drop off after an hour and leave behind a clean wound. Alternatively, using a fingernail or flat card to quickly break the seal around the narrow anterior sucker works to interrupt the feeding. But stressing a feeding leech using salt or fire will cause it to regurgitate and may subsequently result in an infection.

Leech Diversity

Although Alberta leeches do not deserve their creepy reputation, it’s a different story in tropical areas. For instance, the South American Tyrannobdella rex is a small but aptly named leech with oversized teeth. This tiny T. rex (measuring less than 7 cm) favours the nose and mucous membranes of mammals, including humans, where it remains for weeks following satiation. In Alberta, leeches are more mundane, serving as both predator and prey in aquatic ecosystems.

Leeches are a normal part of wetland ecosystems, and while they parasitize some species, they are food for others, like this sandpiper. JOANE REDWOOD

Currently, both Erpobdellidae and Glossiphoniidae are under taxonomic revision, and certain long-standing species are no longer considered valid in North America.3 Meanwhile, new species have likely been hiding in plain sight.4 A major challenge is that leeches are notoriously difficult to examine and identify when collected by standard aquatic sweep net protocols. Those wishing to perform accurate identifications must take special care to preserve leech colour and eye patterns through specific preservation measures, and should rely on using the most current taxonomic keys — what few there are! Fortunately, DNA barcoding is now helping to fill in the large gaps left by conventional morphological identification.

Love or hate them, fear or ignore them, leeches are cosmopolitan in aquatic habitats. While their feeding methods might evoke primitive fears, leeches are just one of the many invertebrates that make up the ecology of our wetlands. If only for the fun of filling in missing taxonomic pieces, I hope that fellow naturalists learn that leeches don’t suck as much as they once thought, and will instead view them with a bit more curiosity.

Cheryl Tebby is an Alberta Biodiversity Monitoring Institute aquatic taxonomist, and assists with the identification of countless numbers of aquatic invertebrates collected annually by the ABMI.

This article originally ran in Nature Alberta Magazine – Fall 2023.