For the Love of Lichens

19 January 2024

BY DIANE HAUGHLAND

Have you ever stepped back and looked at your life and thought, “Huh, this is not what I thought I’d be doing?” If so, I can sympathize. I’ve long loved lichens, but I am a generalist and an ecologist by temperament and training. And yet, here I sit, a full-fledged lichen taxonomist, trying to describe the tiny, root-like attachments on the bottom of a recalcitrant pelt lichen. Are they more mullet-like? Bed-head? Bundled or paintbrush-like? At the end of the day, what a privilege — I wouldn’t have it any other way.

Lichens are fundamentally different from plants or animals. A lichen is not a single organism, but rather an amalgam of multiple organisms involved in a transformative relationship. At their most basic, lichens are a symbiosis of two partners: a photosynthetic organism that makes sugar and a fungus that provides structure through the knitting of their thread-like cells. Added to each lichen body are diverse communities of additional fungi, photosynthesizers, and microorganisms. Together, these communities form the crusts, leaves, wefts of hair, and pixie-sized goblets that make up lichens.

Lichens are all around us, yet few of us know and appreciate them. I leaned into my love of lichens while working with the Alberta Biodiversity Monitoring Institute (ABMI), a provincewide program dedicated to tracking changes in biodiversity. Lichens were one of the lucky groups selected by ABMI to “speak” on behalf of other species. Their selective habitat requirements, long life, and slow growth make them sensitive ambassadors for the many species we can’t monitor.

This article is your invitation to join the club — the “enlichened.”1 Your initiation is simple: meet a few of the wondrous lichens that live among you, quiet but colourful, like lovely, long-lived wallflowers. And perhaps learn a few of the lessons they have to teach. My goal is not to overwhelm you with a systematic, scientific review of the lichen groups in Alberta. Instead, we will meet three colorful species our lab has worked on that illustrate key aspects of lichen diversity and ecology.

Pelt Lichens Reveal Overlooked Diversity

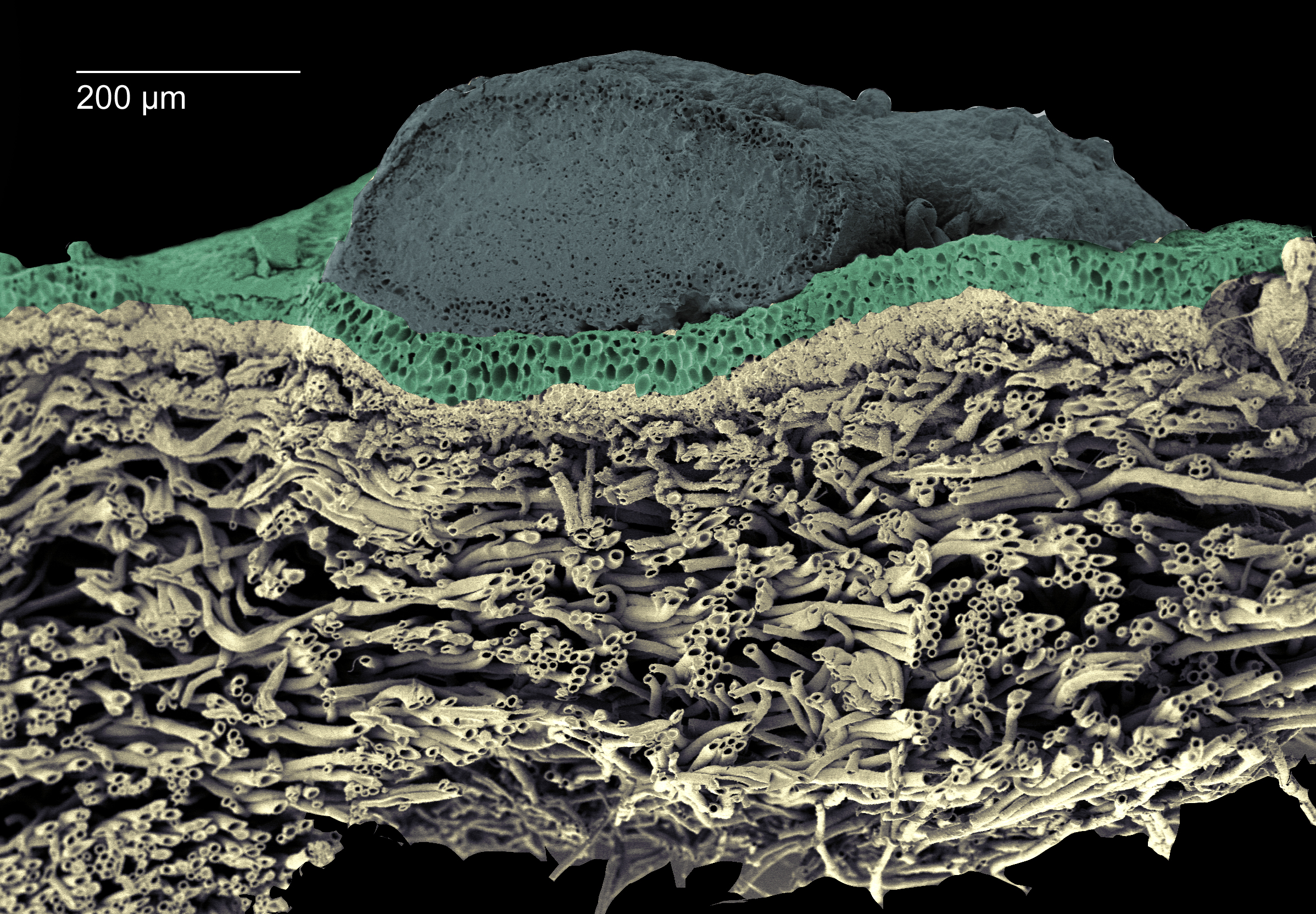

To begin, let’s meet the pelt lichens. Frog pelts and dog pelts catch the eye; they form palm-sized, leaf-like bodies, and they can create large, carpet-like colonies. They live in most terrestrial ecosystems in Alberta, from urban river valleys to remote mountaintops. They help retain soil, help the soil retain water, and provide a home and a meal for many a hungry invertebrate. Pelts are also the largest and most common lichens in Alberta with a cyanobacterium partner. Cyanobacteria are an evolutionary unicorn. They can do something few others can do — take nitrogen directly from the atmosphere and turn it into compounds the rest of us need. By hosting sheets or colonies of cyanobacteria, pelts are nitrogen-fixing phenomes.

There are many reasons to love pelts, but ease of identification is not one of them. Early on, our ABMI lichenology team realized that many of the pelt lichens we collected did not nicely fit the descriptions of existing species. As a taxonomist, this is a significant source of self-doubt. Were we seeing variation within a species? Or were there new species mixed in? To address our doubts, we reached out to an amazing team of lichenologists at Duke University, who have worked for over two decades to answer these very questions.2 By combining boots-on-the-ground field work around the globe with modern molecular methods, they are redefining what we thought was a well-known genus.

Recoloured scanning electron microscope section of a frog pelt. The blueish top layer is a colony of cyanobacteria, and below that lies a layer of green algae. The bulk of the pelt is made of fungal threads. DIANE HAUGHLAND

When we started, there were 28 pelt lichens known in Alberta. After six years and thousands of sequenced collections, we are struggling to understand more than 60 species, many of which are not formally described. Which brings me to my main preoccupation these days: trying to differentiate species that I thought were old friends from outwardly similar but distantly related species. For example, we’ve found that specimens thought to be members of a single, widely distributed, generalist species actually belong to a mix of species, some of which are very specialized and restricted in range. Unrelated species that appear identical are rampant in lichenology. It seems many lichens come to similar conclusions on how best to knit their symbiotic bodies in response to similar environments.

Hooded Sunburst: A Brilliant and Resilient Urbanite

You don’t have to travel to remote areas to find fascinating lichens. Urban lichens, such as hooded sunburst, are worth meeting too. Like many orange lichens, hooded sunburst thrives in the elevated atmospheric nitrogen typical of urban environments. This brilliant beauty grows on trees across Alberta’s urban centres. Its orange, leafy body forms crescent-shaped openings (hoods) that produce tiny, tennis ball-like clones (each ball is made of a few fungal threads and algal cells). It hugs the bark, where it finds shelter from the wind as well as water from rain running down the trunk of the tree.

The origin of this lichen’s orange colour is fascinating. Lichens produce a plethora of chemicals with many different functions. Some make the lichen taste bad (so that herbivores don’t eat them) whereas others regulate the amount of light entering their bodies. Some chemicals have antibacterial and even antifungal properties! In the case of hooded sunburst, the brilliant orange comes from crystals of anthraquinones, chemicals within the lichen that absorb potentially harmful ultraviolet rays. This protects the green algae within the lichen from being overstimulated or damaged, critical when living in open, exposed urban habitats. As lichen taxonomists, we use chemicals like these to help us identify otherwise similar species.

Because lichens vary in their ability to adapt to urban life, the distribution of lichens within a city can tell us about environmental conditions that otherwise are difficult and costly to measure. The range and abundance of each species depends on its tolerance to air- and dust-borne pollutants, as well as its preferred climate. To look at these patterns in Edmonton, teams of students and volunteers braved –30° C weather in 2019 to get up close and personal with tree-dwelling lichens across the city. We received some curious looks. We also found 114 species, an impressive 10% of the known lichen flora of Alberta (including 14 species not previously documented in the province).3 The richest lichen flora is in our ravines and river valley, where cool, moist air can be filtered through the forest canopy, creating conditions that many lichens can enjoy. We also found veritable lichen “deserts,” where lichens were largely absent or restricted to a few hardy species, such as our hooded sunburst. Tracking future changes in these patterns should help us document environmental shifts that also affect human health.

Candy Dot and the Power of Small

While the lichens we have met so far are easily observed, about half of Alberta’s approximately 1,100 lichens are true introverts. These are the crust lichens, many of which hide their bodies within the rock, trees, or soil they grow on. We know them from the limited features they show us, typically small plaques, powdery propagules, or tiny, button-like reproductive structures.

A few crust lichens are more approachable. Meet candy dot, also less elegantly known as fairy puke. Candy dot grows on mosses and logs, visible as a mint-green stain studded with cotton-candy pink “buttons” that produce fungal spores. What a beauty! Recently, Canadians from coast to coast chose lichens to represent their respective provinces or territories. Alberta is a geographically diverse province, home to many lovely lichens, so the competition was stiff, but in the end, candy dot won the nomination. It thrives in the bogs that make boreal Alberta a critical area for caribou, carbon capture, and water cycling. And it likes the mountains too — how very Albertan.

The diversity of tiny lichens like candy dot can be an indicator of ecologically important forests. And some tiny lichens play an outsized role in early successional environments, literally breaking down the substrate they grow on slowly and relentlessly, creating habitat for other species along the way.

Lessons Learned

I have learned so much through working on lichens. It has reinforced the importance of good taxonomy; we shouldn’t overlook the small or get complacent about old friends we think we know. We have a responsibility to the species living in our own backyards and an opportunity to learn from them. The bedrock of biodiversity monitoring is knowing what occurs where, and how each species responds to the bewildering array of natural and anthropogenic forces to which they are exposed. Get the basics wrong and our understanding of species’ niches and conservation needs are muddied. We may mistakenly conclude that rare species are secure, or assess biologically rich sites as just ho-hum.

There are many more lichens to meet, and no doubt you will find your own meaning as you get to know them. A magnifying glass, a camera, and a few resources can get you started. Curiosity, tenacity, and a willingness to get close to the trunk of a tree and turn your eyes earthward will take you even further. I wish you slower but more rewarding walks, and many beautiful future lichen friendships. Welcome to the club — welcome to enlichenment.

Please visit the ABMI lichen website at bit.ly/abmi-lichens for more information. Additional sources of information are provided in the references below.

References

- Trevor Goward coined the term enlichenment. Visit waysofenlichenment.net for an eloquent introduction to lichens and many useful resources.

- Information on the Duke University Peltigera Team and their projects is available at lutzonilab.org/peltigera/project

- Keys, images, and full descriptions of the 114 species known from Edmonton are available at bit.ly/urban-lichens-edmonton

- A short booklet with images of common Edmonton lichens is available on the Nature Alberta website: naturealberta.ca/edmonton-lichens

Diane Haughland is a lichenologist with the Alberta Biodiversity Monitoring Institute, working alongside fellow lichen nerds, er, lichenologists Darcie Thauvette and Jose Maloles. She is also an Adjunct Professor at the University of Alberta in the Department of Renewable Resources. She pinches herself daily to ensure her career in learning, teaching, and applying lichen-related research is not just a dream.

Read the Original Article for this Post

For a richer reading experience, view this article in the professionally designed online magazine with all images and graphs in place.

This article originally ran in the Winter 2024 issue of Nature Alberta Magazine (Vol. 53 | No. 4).