Canada Jays: Grey Ghosts of the Northern Woods

19 January 2024

BY NICK CARTER

With their harsh calls and iridescent plumage, Alberta’s corvid species tend to stand out. But if there is one corvid that has a special place in our hearts, it must be the Canada jay. Its vocalizations are just as varied as other members of the crow family, but more subtle. The song of the Canada jay is known as a “whisper song,” a soft, babbling melody of warbling chirps. It also makes a variety of gentle squeaks and squawks and is skilled at imitating the calls of birds of prey.

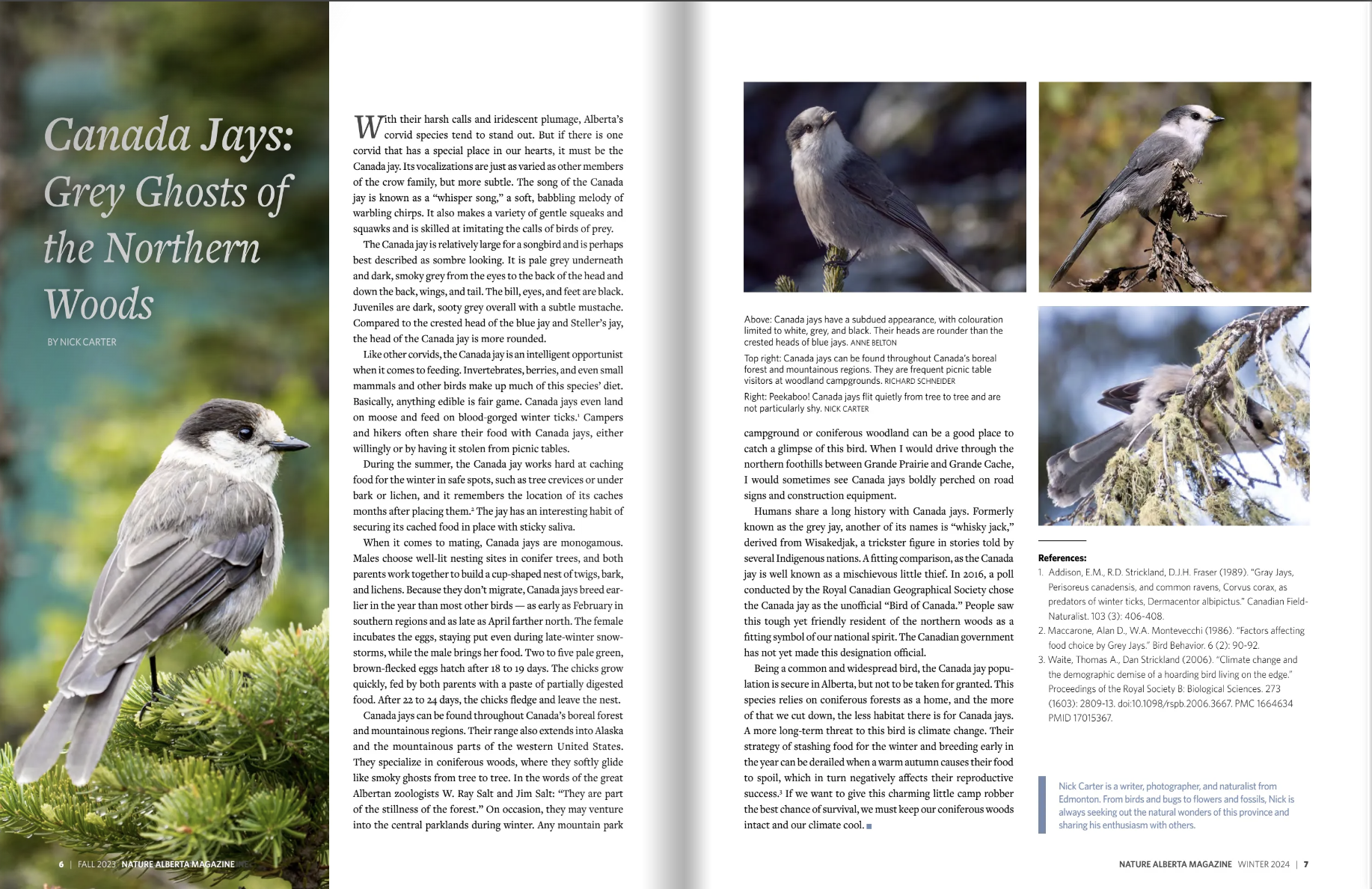

The Canada jay is relatively large for a songbird and is perhaps best described as sombre looking. It is pale grey underneath and dark, smoky grey from the eyes to the back of the head and down the back, wings, and tail. The bill, eyes, and feet are black. Juveniles are dark, sooty grey overall with a subtle mustache. Compared to the crested head of the blue jay and Steller’s jay, the head of the Canada jay is more rounded.

Like other corvids, the Canada jay is an intelligent opportunist when it comes to feeding. Invertebrates, berries, and even small mammals and other birds make up much of this species’ diet. Basically, anything edible is fair game. Canada jays even land on moose and feed on blood-gorged winter ticks.1 Campers and hikers often share their food with Canada jays, either willingly or by having it stolen from picnic tables.

During the summer, the Canada jay works hard at caching food for the winter in safe spots, such as tree crevices or under bark or lichen, and it remembers the location of its caches months after placing them.2 The jay has an interesting habit of securing its cached food in place with sticky saliva.

When it comes to mating, Canada jays are monogamous. Males choose well-lit nesting sites in conifer trees, and both parents work together to build a cup-shaped nest of twigs, bark, and lichens. Because they don’t migrate, Canada jays breed earlier in the year than most other birds — as early as February in southern regions and as late as April farther north. The female incubates the eggs, staying put even during late-winter snowstorms, while the male brings her food. Two to five pale green, brown-flecked eggs hatch after 18 to 19 days. The chicks grow quickly, fed by both parents with a paste of partially digested food. After 22 to 24 days, the chicks fledge and leave the nest.

Canada jays can be found throughout Canada’s boreal forest and mountainous regions. Their range also extends into Alaska and the mountainous parts of the western United States. They specialize in coniferous woods, where they softly glide like smoky ghosts from tree to tree. In the words of the great Albertan zoologists W. Ray Salt and Jim Salt: “They are part of the stillness of the forest.” On occasion, they may venture into the central parklands during winter. Any mountain park campground or coniferous woodland can be a good place to catch a glimpse of this bird. When I would drive through the northern foothills between Grande Prairie and Grande Cache,

I would sometimes see Canada jays boldly perched on road signs and construction equipment.

Humans share a long history with Canada jays. Formerly known as the grey jay, another of its names is “whisky jack,” derived from Wisakedjak, a trickster figure in stories told by several Indigenous nations. A fitting comparison, as the Canada jay is well known as a mischievous little thief. In 2016, a poll conducted by the Royal Canadian Geographical Society chose the Canada jay as the unofficial “Bird of Canada.” People saw this tough yet friendly resident of the northern woods as a fitting symbol of our national spirit. The Canadian government has not yet made this designation official.

Being a common and widespread bird, the Canada jay population is secure in Alberta, but not to be taken for granted. This species relies on coniferous forests as a home, and the more of that we cut down, the less habitat there is for Canada jays. A more long-term threat to this bird is climate change. Their strategy of stashing food for the winter and breeding early in the year can be derailed when a warm autumn causes their food to spoil, which in turn negatively affects their reproductive success.3 If we want to give this charming little camp robber the best chance of survival, we must keep our coniferous woods intact and our climate cool.

References:

1. Addison, E.M., R.D. Strickland, D.J.H. Fraser (1989). “Gray Jays, Perisoreus canadensis, and common ravens, Corvus corax, as predators of winter ticks, Dermacentor albipictus.” Canadian Field-Naturalist. 103 (3): 406-408.

2. Maccarone, Alan D., W.A. Montevecchi (1986). “Factors affecting food choice by Grey Jays.” Bird Behavior. 6 (2): 90-92.

3. Waite, Thomas A., Dan Strickland (2006). “Climate change and the demographic demise of a hoarding bird living on the edge.” Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 273 (1603): 2809-13. doi:10.1098/rspb.2006.3667. PMC 1664634 PMID 17015367.

Nick Carter is a writer, photographer, and naturalist from Edmonton. From birds and bugs to flowers and fossils, Nick is always seeking out the natural wonders of this province and sharing his enthusiasm with others.

Read the Original Article for this Post

For a richer reading experience, view this article in the professionally designed online magazine with all images and graphs in place.

This article originally ran in the Winter 2024 issue of Nature Alberta Magazine (Vol. 53 | No. 4).