Mosses of Alberta: A Miniature Leafy World

18 October 2024

By BRITTNEY MILLER

What do you think of when you hear the word “moss”? Amorphous green emerging from the cracks in your driveway? The green blanket of a forest floor? Maybe you picture reindeer moss (a lichen masquerading as moss in craft stores). Or perhaps you think of the peat moss you use in your garden. Maybe you’ve never even considered it! You wouldn’t be alone — moss is often overlooked. Its small size makes it easy to miss and even harder to understand and identify. But these examples are only a small sampling of the complex story of moss. Despite its small stature, it is just as charismatic as other plants and animals in our province. Moreover, there is a wealth of diversity in form and function, fulfilling important ecological roles.

I love moss. I love the gentle hue of their shimmering leaves in the morning dew. I love connecting at eye level with a decaying log or searching the contours of a cliffside to find that next photo-worthy specimen. I love the joy that comes from finally finding the species description that perfectly fits the plant I’m looking at. I love the ever-evolving journey of learning about mosses, how they relate to each other, and how they relate to us and the health of our planet. My aim here is to share my passion and knowledge of moss by addressing some of the most common questions I’m asked about them. Who knows… you may become a moss lover too!

Are mosses and bryophytes the same thing?

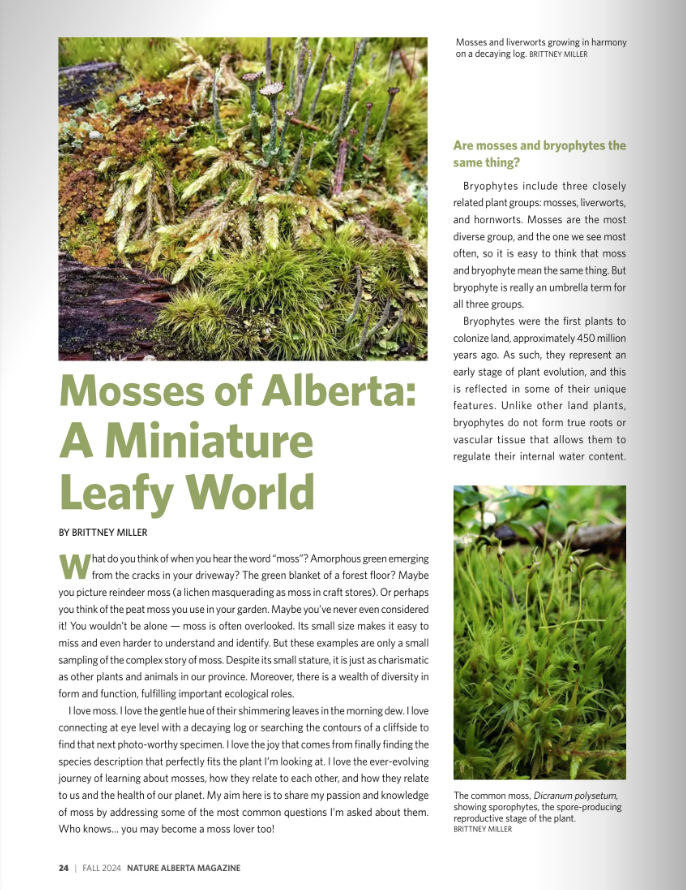

Bryophytes include three closely related plant groups: mosses, liverworts, and hornworts. Mosses are the most diverse group, and the one we see most often, so it is easy to think that moss and bryophyte mean the same thing. But bryophyte is really an umbrella term for all three groups.

Bryophytes were the first plants to colonize land, approximately 450 million years ago. As such, they represent an early stage of plant evolution, and this is reflected in some of their unique features. Unlike other land plants, bryophytes do not form true roots or vascular tissue that allows them to regulate their internal water content. Because of this, they are referred to as non-vascular plants.

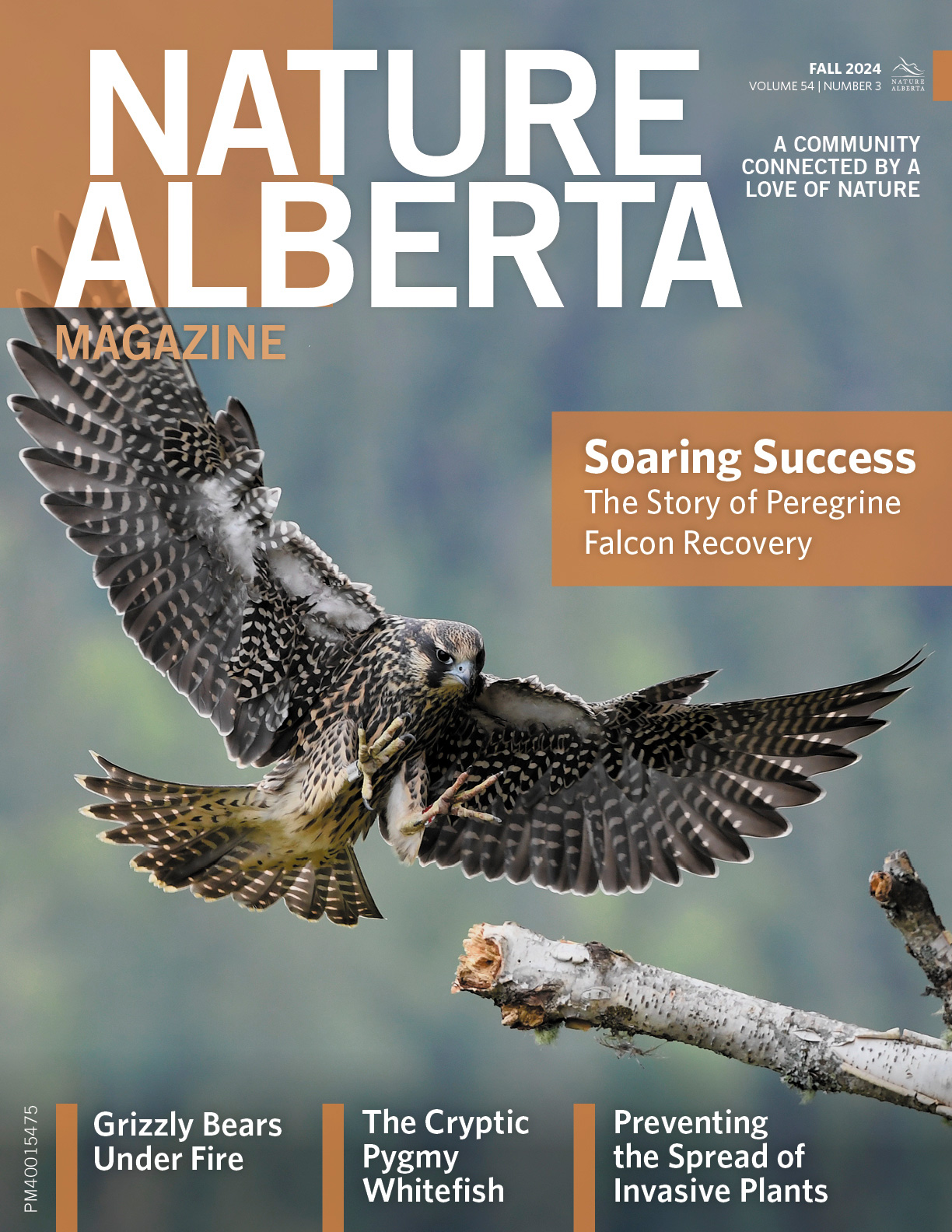

Another distinctive feature of bryophytes is their life cycle. In most plants, a female egg is combined with male pollen to produce a seed that has two sets of chromosomes, one from each parent. Not bryophytes. Instead of seeds, they release spores, which have only a single set of chromosomes. These spores grow into male or female plants (or both), with just a single set of chromosomes in each cell. To reproduce, the males release sperm into the environment, which has to make its way to the female eggs. There the egg and sperm fuse to produce an embryo, which eventually undergoes a special type of division to form the spore-producing structures (kind of like a bryophyte version of a flower). The spores are tiny (less than 0.05 mm wide) and can travel hundreds of kilometres via wind.

Bryophytes also commonly reproduce by cloning themselves. Specialized structures form on leaf tips or roots or other parts of the plant to do this. Sometimes it’s simply leaf tip fragments themselves. When these structures fall off, they can form an entirely new plant genetically identical to its parent.

No roots? No vascular tissue? How does it survive?

Bryophytes have adaptations that allow them to survive even without having roots to draw in nutrients and water, or vascular tissue for water retention. On a hot, dry day you may notice that all the moss you see looks… well… dead. But go back after a rain shower you will see that all the moss has seemingly come back to life, looking green and luscious.

Bryophytes have developed a tolerance to drying out. When their environment is dry, they can slow their metabolic function to the lowest possible level, going into dormancy and taking on that shrivelled-up appearance while they wait for moisture to become available again. When that rain shower comes, they turn their metabolism back on and get right back to growing. Furthermore, their leaves are typically only one cell thick, allowing water and nutrients to be passively absorbed. Some mosses are better at tolerating dehydration than others. You may have noticed lovely boulders in the mountains that are fully exposed to the sun and heat and yet are still covered in moss. These are species that excel at being dormant. Conversely, not far away, you may come across a creek hidden in the trees, where an abundance of entirely different moss species exists. These are species that prefer constant exposure to water.

Adaptable spores are another important strategy for dealing with environmental variability. Spores can sit in the soil and wait for conditions to be just right, and once they are, they will grow into a healthy little plant. Incredibly, spores have been shown to survive 4,000 years of being trapped in ice! These spores patiently waited for millennia and then, when given the right conditions, grew!

What does moss “do”?

Mosses (and all bryophytes) have many important ecological roles. They provide habitat for many invertebrates — I’ve often discovered little rotifers and nematodes when dissecting bryophyte samples, and even the occasional water bear (more formally known as tardigrades). They also provide soft nesting material for small mammals, amphibians, and birds. They are one of the first organisms to colonize after a disturbance, stabilizing the soil and facilitating nutrient cycling, which then allows vascular plants to grow.

One of their most newsworthy roles is carbon storage. Peatlands, which are wetlands with organic material accumulations over 40 cm thick, are mainly composed of mosses such as Sphagnum. The moss in peatlands decays slowly because of the waterlogged, acidic environment, and as a result the mosses in peatlands can be hundreds of years old and still identifiable. This slow decaying process is also why peatlands are so proficient in carbon storage. As the mosses grow, they take in carbon from the atmosphere, and that carbon is retained in the peatland. (For more information on peatlands, see the Summer 2024 issue of Nature Alberta Magazine).

Can you eat moss?

I love this question, and I actually get it a lot. The answer is, yes, you can, but there is little to no point. Moss has almost no nutritional value and the crude-fibre texture is rather unpalatable. Yes, I’ve tried! I marinated and fried up Scorpidium scorpioides, a rather juicy and turgid moss occurring in nutrient-rich water, during a field season at Alexandra Fiord, Ellesmere Island. Our field crew all tried it out of sheer curiosity (and maybe a little bit of insanity after having been up there for months). We regret nothing, but would not do it again… Probably not, anyway.

Does anything eat moss?

Although not fit for humans, many small creatures love to feast on mosses. Invertebrates such as isopods and mites have been documented chomping away at various parts of mosses, the developing spore-producing structures offering the juiciest morsels. Slugs, snails, and even lemmings happily munch away at mosses as well.

Do mosses compete like vascular plants do?

Mosses may seem like the mild-mannered version of flowering plants, but some studies have found that they do indeed compete with each other. If the environment changes and is less favorable for one species, another species more suited to this change is happy to take its place.

Where do I find moss?

Everywhere! If you’re looking, you can find bryophytes growing on trees in your neighborhood, on wet soil in river valleys, even in your backyard if the conditions are right. Bryophytes occur all across our province, forming peatlands in our boreal forests and covering and stabilizing soil in prairie grasslands. Although they occur everywhere, if you want to see the most diversity in one place, then moist, protected, rocky nooks in the mountains are your best bet.

How do I learn more about mosses?

There are over 800 species of bryophytes in Alberta. In my recent book, A Guide to the Common Mosses and Liverworts of Alberta, I provide an introduction to 170 of the most common species. Each species in this book has a field-based description in non-technical and technical terms, a large field photo, a macro photo of leaves, a watercolor illustration, habitat information, a map showing where the plant can be found in Alberta, and a list of species that it could be commonly confused with. There is also an illustrated key and a guide to species by features to help with identification. The goal of my book, akin to this article, is to share my love and knowledge of the miniature leafy world of mosses. It is a beautiful and intriguing part of our province’s natural world!

Brittney Miller first fell in love with moss after taking a field botany course during her B.Sc. at the University of Alberta. She completed M.Sc. research on ancient bryophytes emerging from retreating ice patches in the southwest Yukon. Her passion for bryophytes has taken her to glaciers in Canada’s Arctic (Ellesmere Island, Nunavut) as a researcher, and throughout the province of Alberta as a consultant. She has previously worked for the Alberta Biodiversity Monitoring Institute (ABMI) doing bryophyte taxonomy and currently works as a vegetation scientist for Vertex Professional Services.

Read the Original Article for this Post

For a richer reading experience, view this article in the professionally designed online magazine with all images and graphs in place.

This article originally ran in the Fall 2024 issue of Nature Alberta Magazine (Vol. 54 | No. 3).