Action for an Icon

Why Do Alberta’s Caribou Keep Declining, and What Can We Do About It?

BY RICHARD SCHNEIDER

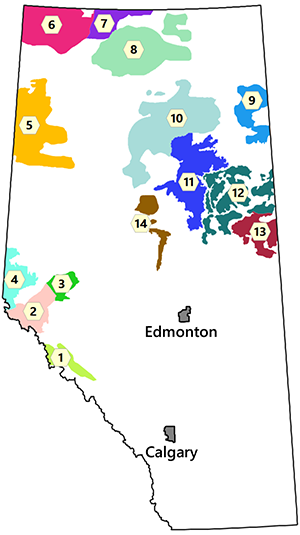

Woodland caribou were once distributed throughout Alberta’s forested lands but today they are restricted to 14 core ranges.

The caribou is one of Canada’s most iconic species; its image is still featured on Canadian quarters. But across the country, the species is not doing well. Despite its high profile and the millions of dollars we’ve poured into research, the caribou’s story is one of progressive decline. As a conservation biologist beginning my career in the early 1990s, I’ve had a front-row seat to the unfolding drama. Here I will explore the key challenges that make caribou conservation so difficult and provide an unvarnished perspective on what needs to change.

Caribou, Wolves, and Moose

The caribou that reside in Alberta are a subspecies referred to as woodland caribou. Unlike the barren-ground caribou of the far north, known for their large migratory herds, woodland caribou only form small groups and do not undertake long-distance migrations. Historically, they were distributed throughout the forested parts of Alberta, but over the last century their range has contracted and become fragmented.

The main limiting factor affecting caribou populations is wolf predation. Caribou are not much larger than deer and are relatively easily killed by wolves. Their strategy is one of avoidance — woodland caribou reside in habitats that wolves generally ignore. To understand how this works we need to look at the system from the wolf’s perspective.

Left: Wolf predation is the main limiting factor on caribou populations. KELTIE MASTERS

Right: Moose form the main prey base for wolves in boreal systems. RICK TALLAS

In boreal forests, moose are ubiquitous, elk are generally absent, and deer are uncommon (at least historically). Therefore, moose form the main prey base for wolves in boreal systems. In the past, wood bison would have been important as well, in localized areas. Wolves also eat rodents, hares, and other animals, but these species cannot support a wolf pack over the course of the year; it’s moose that wolves ultimately depend upon.

Moose are browsers, mainly eating the leaves and twigs of shrubs and young trees. This means moose are usually found in upland forests, especially young forests regenerating after fire. The north’s vast peatlands, comprising more than a third of Alberta’s boreal region, offer little of interest to moose. Most peatlands are either open, with a ground cover of moss and lichen, or covered with scraggly, lichen-covered black spruce and tamarack. Either way, there is not much to eat if you are a moose and so these areas are generally avoided. And without moose, there is little to attract wolves either.

Caribou use peatlands to spatially separate themselves from moose and wolves, which prefer upland forests. R SCHNEIDER

It follows that, if you are a caribou trying to avoid being eaten, peatlands are the place to be. The trouble is, you still need to eat, and peatlands are challenging habitats for most herbivores. But caribou are not like most herbivores. They do just fine on a diet of lichens, mosses, and conifer needles — exactly what’s on the menu within peatlands.

Spatial isolation together with a low natural rate of reproduction provide a winning strategy for caribou survival.1 There are simply not enough caribou present to make it worthwhile for wolves to spend time hunting in peatlands, which are otherwise devoid of prey. The occasional caribou is taken through chance encounters, but wolves spend most of their time in upland areas, where the moose are. This is how caribou have been able to persist in Alberta’s boreal region for thousands of years, despite their inherent vulnerability to wolf predation.

The same basic pattern applies in the mountains. But instead of peatlands, mountain caribou inhabit large areas of old-growth forest. Older coniferous forests offer little in the way of browse for moose, but plenty of arboreal and ground lichen for caribou.

When wolf populations are high, few young caribou survive to their second year. ALAIN CARON

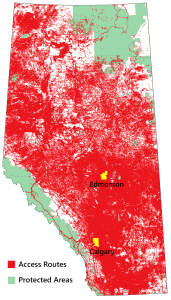

Access routes, shown in red, are extensive in Alberta, mainly because of oil and gas development and forestry operations. Data from Global Forest Watch Canada.

A Forest Transformed

Like many large herbivores, caribou were subject to overhunting in the 19th and early 20th centuries. However, the declines were much less extreme than for many other game species, mainly because caribou were difficult to access. There had been some range contraction by the 1950s, but caribou were still widely distributed across Alberta’s forested lands and individual populations remained viable.

Over the past 70 years, the overriding threat to caribou has been habitat transformation resulting from the industrialization of Alberta’s forests.1 First came large-scale logging operations in the foothills, beginning in the 1950s. Then oil and gas extraction expanded from the prairies into the foothills and boreal region. This brought roads, seismic lines, and utility corridors into forested lands and facilitated further expansion of forestry into the north. By the 1980s, there was virtually no part of the province that had not been accessed, other than the far northeast corner.

The effects of these transformations on woodland caribou were understood early on. Biologist Jan Edmonds summarized the process in a paper in 1988, and the basic thesis she put forward has been verified by dozens of research studies since then.2 In a nutshell, forestry cutblocks, oil and gas wells, seismic lines, and access corridors all entail cutting mature forest and resetting the successional clock. At the regional scale, this means more food for moose, leading to growing moose populations. This in turn means more wolf packs and more chance encounters between wolves and caribou. Increased forest access also results in increased poaching and vehicle collisions. The net effect has been a steady decline in caribou populations across the province.3

Understory vegetation flourishes after forest harvesting, providing plenty of browse for moose. ELI SAGOR

Initial Conservation Efforts

Initial caribou conservation efforts were led by provincial wildlife managers. They began by curtailing sport hunting of caribou in 1981, and then designating the species as provincially threatened in 1985. They also recommended habitat protection; however, they had little authority over the decisions that mattered. While wildlife managers were recommending the retention of intact forest for caribou, other branches of government were allocating vast tracks of caribou habitat for new industrial developments.

The 1990s were a period of heightened environmental salience, and all across the country there were high-profile public protests over unsustainable forestry practices.4 Thereafter, stakeholders began to be included in resource decision-making. In Alberta, caribou committees and working groups were established at the provincial, regional, and range levels. The stakeholders within these groups were roughly divided into two camps: those who sought substantive protective measures for caribou (government wildlife managers, conservation groups, and Indigenous communities) and those who favoured the status quo (most resource companies and local communities). Unsurprisingly, these two camps could not find common ground. Elected officials, for their part, remained on the sidelines and made no attempt to resolve the impasse.

The ensuing decades were characterized by relative stasis. Every few years a new strategy or set of management guidelines would be released, but meaningful on-the-ground protection of caribou was not forthcoming. The only area of substantive progress was in research. The resource sector was unwilling to entertain constraints on development, but it was willing to provide funding for caribou field studies. There was a hope that such research would lead to win-win solutions that permitted resource extraction while also maintaining caribou. Research efforts could also be cited as evidence of conservation effort, offsetting the lack of demonstrable change on the ground.

The caribou's story is one of progressive decline. PEUPLELOUP

From the perspective of caribou, this period was disastrous. Industrial development continued to expand and intensify, forests continued to be transformed, and caribou populations continued to decline.4 By the late 2000s, Alberta’s caribou were acknowledged to be among the most threatened in Canada. All the while, poll after poll showed that Albertans placed a high priority on the conservation of biodiversity, including the recovery of caribou, even if it came at the expense of resource jobs. Why the disconnect?

The root of the problem is that caribou conservation demands politically challenging choices between environmental protection and economic development. There are no win-win solutions here: caribou and industry simply don’t mix. Furthermore, caribou are distributed across much of Alberta’s forested lands, which means that substantive efforts to protect caribou will impact the resource sector and rural communities broadly. This has been viewed as politically dangerous ground by successive Conservative governments, whose core voting base resides in rural Alberta. As a result, elected officials have been keen to offload these tough decisions to stakeholder working groups rather than tackle them directly. The trouble is, these working groups were never given the mandate or the authority to resolve broad land-use conflicts. The result was decision by indecision.

The Feds Step in

Canada’s Species at Risk Act was passed in 2002 and the boreal population of woodland caribou was listed as “Threatened” the following year. This prompted the development of a federal caribou recovery strategy in 2012, which marked a turning point in caribou conservation in Alberta.5 Not only was the bar raised for recovery actions, but also, for the first time, these actions were non-discretionary.

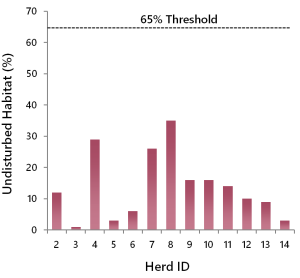

What differentiated the new federal strategy from earlier provincial efforts was the hard line it took concerning the identification and management of critical habitat. The federal recovery team defined critical habitat in functional terms: within each range, a minimum of 65% of the area would have to be maintained in an undisturbed state. The provinces were given until 2017 to develop range plans that would describe how the 65% target would be achieved for each herd.

In all Alberta caribou ranges, the current amount of undisturbed habitat is far below what is needed for caribou viability (range numbers correspond to the range map). Data from the Alberta Caribou Range Plan.6

Alberta failed to complete individual range plans by the 2017 deadline. However, it did release a provincial range plan in 2017, which was meant to serve as a template for future herd-level planning.6 The provincial range plan described how 65% of each range would be maintained in an undisturbed state through an integrated landscape management system. The centrepiece of the proposed system was a multi-use access network that would be developed for each range. According to the plan, it would be possible, using spatial optimization techniques, to design a network that provided access to virtually all resources while still achieving the 65% intact habitat target. The plan also included measures to reduce habitat fragmentation from forestry operations by aggregating harvest blocks.

The provincial range plan acknowledged that achieving the 65% undisturbed target would require substantial restoration efforts because existing levels of disturbance were very high in all ranges. Under the plan, restoration would be applied to industrial features that were no longer in use, particularly seismic lines and well sites. In addition, access routes would gradually be transitioned to the new optimized network. Given the extent of the existing footprint, it was estimated that it could take 50 to 100 years to achieve the 65% undisturbed target in all ranges. The range plan prescribed the use of wolf control to maintain the viability of caribou herds during the extended restoration period.

The Alberta Caribou Range Plan proposed several new protected areas in northwest Alberta.6 Caribou ranges are outlined in black.

Significantly, the range plan also included protected areas as a recovery measure. Three large sites in northwest Alberta were identified as proposed caribou reserves. These three sites provided the best opportunity for full protection because the level of resource conflict was minimal, in contrast to most other caribou ranges.

Though the 2017 range plan had serious deficiencies — chief among them the long period required for restoration and the need for prolonged, widespread wolf control — this was the first caribou management plan with a meaningful chance of success. Moreover, the plan amounted to a cumulative effects management strategy that would benefit many species besides caribou. Such a strategy had been promised under the Alberta Land-Use Framework but was never implemented. The caribou range plan provided a working model for how it could be done.

What Does the Future Hold?

It’s been more than five years since the 2017 range plan was released, providing enough time for us to gauge progress. An optimist would point to several positive developments. First and foremost, most provincial caribou herds have stopped declining (for the first time in decades). Second, range plans are now being developed for individual herds and two have been completed as of this writing. The completed plans reconfirm Alberta’s intention to achieve the objectives and targets in the federal recovery strategy and they incorporate the core strategies outlined in the 2017 provincial range plan. Third, several seismic reclamation projects are now underway.

Unfortunately, there are also reasons for pessimism. To begin, the three large protected areas identified in the 2017 plan were abandoned after the local municipality pushed back. Giving up full protection in exchange for a regional management plan which allows for further industrial development is a serious blow. It’s even more troubling when you consider that the three affected caribou herds had the highest potential for long-term viability of all provincial herds and that the level of resource conflict here was lower than anywhere else.

Woodland caribou. ALAIN CARON

Another reason for pessimism is that, in the five years since the provincial range plan was released, not a single road has been reclaimed. Yet all the while, new forestry cutblocks, new oil and gas wells, and new roads were added to the already excessive levels of disturbance within caribou habitat. And while some seismic lines have been reclaimed, on an ad hoc basis, new lines are still being cut. Add everything up and we are today farther from the target of 65% intact habitat than when the plan was released five years ago. This is hardly encouraging progress.

It gets worse. In late 2021, then-Forestry Minister Devin Dreeshen announced that the government planned to increase the rate of forest harvesting by 30%. This is directly contrary to the needs of caribou and indicates that, at the highest levels, the UCP government has no real commitment to caribou recovery or to sustainable land-use in general. Instead, the government seems intent on turning the clock back to the 1980s, when industrial development trumped all other land uses. Under these circumstances, the prospects for the 2017 range plan are bleak. A plan is like a hot-air balloon; without a flame to provide lift, it isn’t going anywhere. In a planning context, political will is the flame needed for implementation.

Finally, the only reason that caribou populations have stabilized is because we are now killing wolves on a massive scale. Wolves are being shot, trapped, and poisoned in seven caribou ranges across the province. The ecological disruption arising from the removal of an apex predator is a serious concern, as are ethics of wolf control. Most (though not all) conservationists have reluctantly accepted wolf control as a temporary measure needed to keep caribou viable until their habitat has been restored. However, it is increasingly apparent that wolf control is being used as an alternative to meaningful and timely restoration. Support for wolf control is likely to vanish under these circumstances.

In summary, caribou present an extremely challenging case because they are widely distributed and require large areas of intact habitat to survive. This pits caribou against the resource sector and the rural communities that depend on this sector for their livelihood. As such, this is a political problem that will not be resolved through the development of range plans. These plans are a necessary component of caribou recovery, but without a change in political will there is little hope of meaningful implementation.

Caribou mom with baby. PEUPLELOUP

Presented with competing values and societal divisions, we face a difficult question: who gets to decide how public lands are managed? Roughly three-quarters of Albertans reside in urban centres and most of these individuals would protect caribou in a heartbeat, even if it meant some job losses. But would it be fair to allow urbanites to unilaterally force through land-use decisions that could disrupt the lives of rural Albertans? Arguably not. On the other hand, should individuals who live in remote areas have a veto over decisions concerning public lands? Even if it means that species such as caribou would disappear? This doesn’t seem right either. Yet this is exactly what happened in northwest Alberta in 2018. Even though there are over 4.5 million people in Alberta, a petition led by County of Mackenzie, with a population of around 11,000 people, was enough to squash the proposed creation of caribou reserves in that area.4

Clearly, an approach is needed that balances the values and needs of rural Albertans with those of broader society. This presents a political challenge for Alberta’s Conservatives, whose core supporters are mostly rural. But it’s not an impossible challenge. A decade ago, the Stelmach government managed to find a way forward through the Land-Use Framework. Unfortunately, Stelmach’s balanced approach was abandoned by the Kenney government, which instead emphasized industrial development over other values. The policy agenda being advanced by Premier Smith is even more extreme and disconnected from broad public concerns and priorities. The future for caribou is exceedingly bleak if Danielle Smith is elected Premier in the spring of 2023.

Other than a change in government, the main hope for caribou is the Species at Risk Act. Alberta has until 2024 to complete its range planning for all herds. If these plans are deemed inadequate for caribou recovery, the province may be compelled to do better through the “safety net” provisions of the Species at Risk Act. However, it is unclear whether the federal government will choose to get into a fight with Alberta over this issue. Moreover, we are moving into a legal gray area, so it is very hard to predict how things will play out.

If you can't bear to stand by while Alberta’s caribou slowly disappear and you can’t tolerate the idea of killing wolves indefinitely, I urge you to take action. We have an election coming up, providing all of us an opportunity to hold our government to account and to ensure that environmental values are not disregarded. Over the past four years, in addition to the neglect of species at risk, we have seen proposals to delist provincial parks, proposals to expand coal mining in the Eastern Slopes, and proposals to increase forestry beyond sustainable limits. It’s time for a change in direction, and your vote can make it happen.

References

- Peters, W., M. Hebblewhite, N. DeCesare et al. (2012). Resource separation analysis with moose indicates threats to caribou in human altered landscapes. Ecography, Vol. 35.

- Edmonds, J (1988). Population status, distribution, and movements of woodland caribou in west central Alberta. Canadian Journal of Zoology, Vol. 66.

- Stewart, F., J. Nowak, T. Micheletti et al. (2020). Boreal caribou can coexist with natural but not industrial disturbances. Journal of Wildlife Management, Vol. 84.

- Schneider, R. (2019). Biodiversity Conservation in Canada: From Theory to Practice. Canadian Centre for Translational Ecology, Edmonton, AB.

- Environment Canada (2012). Recovery Strategy for the Woodland Caribou (Rangifer tarandus caribou), Boreal population, in Canada. Environment Canada, Ottawa, ON.

- Government of Alberta (2017). Draft Provincial Woodland Caribou Range Plan. Government of Alberta, Edmonton, AB.

Richard Schneider is a conservation biologist who has worked on species at risk and land management in Alberta for the past 30 years. His recent book, Biodiversity Conservation in Canada: From Theory to Practice, includes a detailed case study on Alberta’s caribou.

This article originally ran in Nature Alberta Magazine - Winter 2023.