Environmental Advocacy: The Anatomy of a Campaign

By Richard Schneider

Environmental protection efforts occur across a range of scales, from small community programs to large provincial or national campaigns. The types of issues addressed and the approaches used are also highly varied. Despite this variability, there is a basic set of principles that contribute to a positive outcome, and in this article we will work through these principles. The focus will be on biodiversity conservation because this is where my 31 years of experience have been centred. However, the basic concepts are fully applicable to other forms of environmental protection.

How Are Land-Use Decisions Made?

It is tempting to think of environmental problems as arising from a lack of knowledge or awareness, leading to calls for more research and better communication. “If people only understood what was happening, things would surely change!” While science and awareness are certainly parts of the puzzle, there is usually more to it. In most cases, there is a conflict between competing social objectives that underlies the issue. Therefore, it is best to approach environmental problems within the context of land-use decision making.

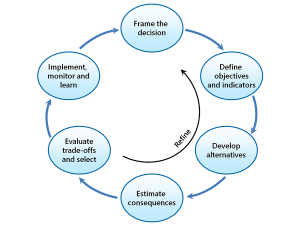

The state-of-the-art approach to land-use decision making is referred to as structured decision making, which comprises a defined sequence of steps (see the diagram below). The basic idea is to reveal trade-offs among competing objectives and to identify a management approach that best balances those objectives. The role of science is to generate potential approaches and to predict how these approaches are likely to perform against each of the selected objectives. Note that science can only inform decisions, it cannot make decisions. The choice of how best to balance implicit trade-offs is ultimately a social/political one.

In practice, structured decision making has mainly been applied to well-defined problems of limited scope. For example, it has been used to set limits on water withdrawals related to oilsands mining along the Athabasca River. A structured approach to planning is also used to guide development within urban centres. Planning at broader scales has been much less successful.

A case in point is the Alberta Land-Use Framework, completed in 2008 after several years of extensive public and technical input. The Land-Use Framework explicitly recognized the finite capacity of the land and the need to grapple with trade-offs through regional planning. It also proposed the establishment of a unified land-use manager that would be responsible for regional planning and would coordinate the activities of individual government departments. Unfortunately, when political priorities changed in the 2010s, the initiative lost steam. Only two of the seven regional plans were completed, and the entire process was eventually abandoned.

In the absence of a formal planning process, governments make ad hoc decisions, partially dictated by party ideology and partially driven by external pressure. There is also a substantial amount of decision by indecision. This is the context that environmental advocates often operate in — essentially a wrestling match among stakeholders pursuing conflicting goals, officiated by a referee that is far from neutral.

Campaign Planning

In a structured planning system, environmental advocates serve several roles:

- Help define the scope of the process so that relevant environmental processes are included.

- Ensure that environmental objectives are properly articulated, with appropriate indicators.

- Contribute to the suite of management actions that are considered as options.

- Advocate for the environment when trade-off decisions are being made

In the absence of a formal planning process, environmental advocates have to advance their goals within the public sphere through some form of campaign, large or small. In other words, we have to get in the wrestling ring with other stakeholders and battle it out. And since we are not the largest or strongest player, success depends on sound strategy and tactics.

The first step is to define the desired outcome; it is important to begin with the end in mind. Advocacy is more than simply expressing outrage over a development proposal or government policy. It is about achieving meaningful change on the ground. So you begin by setting a destination and then crafting a plan to get you there.

Next, determine whether a campaign is actually warranted. Is the issue important enough to justify the time and energy needed to have a meaningful impact? Is there a realistic path to success given the available human and financial resources? This is not an easy decision. As a general rule, smaller localized issues are easier to resolve than issues with broader scope. But sometimes it is worth taking on a broad issue with a high level of conflict because the overall impact is much greater.

If the decision is to proceed, the next step is to frame the issue. What core values are at stake? What are the competing objectives and what is the nature of the trade-offs among them? The aim is to understand the fundamental conflicts from a range of perspectives, not just your own. It’s also important to consider the spatial scope of the issue and to identify the relevant decision maker. In many cases, what seems like a local problem is really a symptom of a policy failure at a higher level.

A few additional questions to consider when framing the issue are:

- Who has the authority to make the necessary decisions?

- What is the decision-making process?

- Whose voices are decision makers listening to?

- Does public opinion matter?

- What else is motivating decision makers?

- Does a window of political opportunity exist?

Campaign planning also needs to consider allies and opponents. The odds of success are greatly increased if your group is not the lone voice advocating for a particular outcome. For example, in the campaign against expanded coal mining in Alberta's East Slopes, conservation groups led the charge, but it was the addition of other voices, including local landowners, municipalities, and outspoken country singer Corb Lund that arguably tipped the balance in favour of protection. It is also worth exploring the level of public support for the position you are advancing and as well as the level of government support. Even if high-level political support is lacking, there may be managers within specific departments willing to champion the issue.

It is also important to understand who your opponents are and what their objectives are. By clarifying the key points of conflict, you can begin to develop workable solutions. The idea is not to engage in preemptive compromise, but to articulate a realistic path forward that addresses the concerns of your opponents to the extent possible. This approach will receive greater support by government and the public than forcing them to make a hard choice between opposing positions.

Lastly, a campaign requires resources. The foundation of any campaign is a group of individuals willing to put time and effort into the initiative. For local issues, a small volunteer group may suffice. But for larger campaigns, particularly if public outreach is required, financial resources may be needed for contracted staff and communications.

Taking Action

Once the planning is done, it’s time to take action. In most cases, this will entail some form of communication. The aim is to raise awareness and to persuade various target audiences to support your position. Begin by introducing the problem and explaining why your audience should care. If you can’t make a connection with your listeners they’re unlikely to support you. Next, articulate your “ask.” What change or action are you looking for?

A detailed discussion of persuasive argument is beyond the scope of this article, but some key points to consider include:

- A simple, clear, and achievable proposal is best.

- Articulating a workable alternative vision is more powerful than simply opposing something.

- Provide sound arguments that support your position and highlight the weaknesses in the opposing position (tailored to your audience).

- For public audiences, strong visuals help to create an emotional connection — vital for public engagement

Taking action also entails developing partnerships with allies and encouraging them to engage. The broader the issue and the higher the level of conflict, the more partners are needed. Note that formal coordinated alliances are not that common. Rather, groups cooperate where their common interests align, with each group playing the role it's best suited to. Once the campaign achieves visibility and profile, it will often stimulate vocal opposition, and this should be addressed through respectful counterarguments.

At some point, not necessarily at the outset, you will need to engage directly with the relevant decision makers. Sometimes, a successful campaign will lead to a formal decision-making process where trade-offs can be explored and fairly dealt with. In other cases, your relationship with the government will remain adversarial and change will only come through the application of sufficient political pressure. A few points to consider include:

- At an early stage, ensure that decision makers are aware of your concerns and the changes you are looking for.

- Come at the issue from the land manager’s perspective and, if possible, offer them a workable path forward.

- Be sure to position yourself as representatives of a broader constituency (which conservation groups usually are).

Lastly, patience is often required. In many cases, the existing political climate may be unfavourable for the kinds of changes you are advocating for, making progress difficult. The campaign may need to focus on foundational efforts during this period, raising awareness and building allies until a window of opportunity arises. This is also a good time to refine tactics and strategies and to try new approaches.

A more detailed treatment of the information in this article, including two case studies, is available in an associated YouTube presentation. A broader treatment of biodiversity conservation is available in my book Biodiversity Conservation in Canada: From Theory to Practice, published as a free open text by the University of Alberta.