Alberta’s Wrens

16 April 2025

By NICK CARTER

Birders use a nickname to refer to the many small, brownish songbirds that are tricky to distinguish from each other: “little brown jobs,” or LBJs. Perhaps no birds are more deserving of the moniker than the wrens of Alberta.

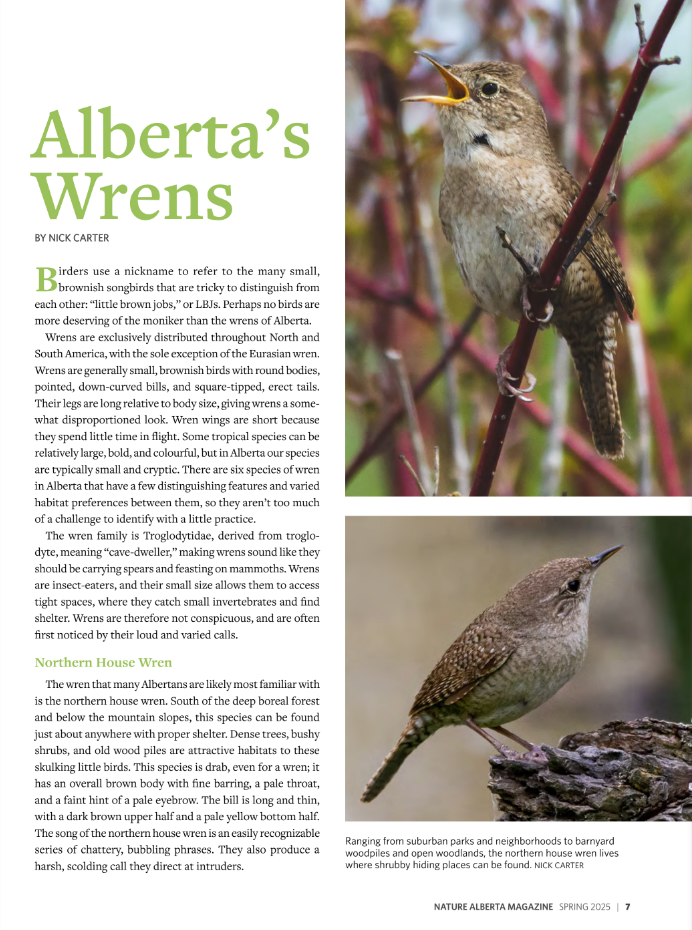

Wrens are exclusively distributed throughout North and South America, with the sole exception of the Eurasian wren. Wrens are generally small, brownish birds with round bodies, pointed, down-curved bills, and square-tipped, erect tails. Their legs are long relative to body size, giving wrens a somewhat disproportioned look. Wren wings are short because they spend little time in flight. Some tropical species can be relatively large, bold, and colourful, but in Alberta our species are typically small and cryptic. There are six species of wren in Alberta that have a few distinguishing features and varied habitat preferences between them, so they aren’t too much of a challenge to identify with a little practice.

The wren family is Troglodytidae, derived from troglodyte, meaning “cave-dweller,” making wrens sound like they should be carrying spears and feasting on mammoths. Wrens are insect-eaters, and their small size allows them to access tight spaces, where they catch small invertebrates and find shelter. Wrens are therefore not conspicuous, and are often first noticed by their loud and varied calls.

Northern House Wren

The wren that many Albertans are likely most familiar with is the northern house wren. South of the deep boreal forest and below the mountain slopes, this species can be found just about anywhere with proper shelter. Dense trees, bushy shrubs, and old wood piles are attractive habitats to these skulking little birds. This species is drab, even for a wren; it has an overall brown body with fine barring, a pale throat, and a faint hint of a pale eyebrow. The bill is long and thin, with a dark brown upper half and a pale yellow bottom half. The song of the northern house wren is an easily recognizable series of chattery, bubbling phrases. They also produce a harsh, scolding call they direct at intruders.

Northern house wrens migrate into the province in May and head down to the southern United States and northern Mexico again by mid-September. Like house sparrows and house finches, northern house wrens are comfortable in close proximity to people. Older suburban neighborhoods and wooded rural properties will often host a pair of them. They are cavity nesters and will readily use bird boxes as well as other human-made nooks and crannies, filling nest cavities with small sticks. As with all wrens, the male makes several different nests within its territory, and the female will choose her preferred nest within which to lay her eggs. This behaviour can annoy people with multiple bird boxes on their property, because a single pair of northern house wrens fill all the boxes with sticks and then leave them vacant but unusable to other birds.

Winter Wren and Pacific Wren

The winter wren is a scampering dweller of the tangled forest undergrowth. This species was given the name winter wren because it winters in the eastern United States, and so it is encountered by American birdwatchers during the winter. In the warmer months, this is a species of the north woods. In Alberta, they breed in the boreal forest, nesting among the roots of fallen logs or abandoned woodpecker holes. People in central and southeastern Alberta can hope to see this species in spruce woodlots as it passes through during its late-summer migration.

Winter wrens are small and round, even by wren standards. The bill is dark, thin, and straight. The tail is short and stubby and upheld in characteristic wren posture. Winter wrens are darker brown than house wrens, with barring on the belly, wings, and tail. The face and throat are pale in colour, and there’s a noticeable white eyebrow. The male produces a tumbling, whistling call that can last for up to 10 seconds. Males and females both give chirping, sparrow-like calls when agitated. Their vocalizations are often the only way of knowing that one is nearby; thankfully, winter wrens are loud. Patient birdwatchers must hold still and watch for a little brown flash of movement among the jumbled vegetation.

The winter wren is closely related to the extremely similar Pacific wren, a species of the coniferous forests between the Rocky Mountains and the Pacific coast. The best way to tell these two species apart where their ranges overlap is differences in voice, which also prevent them from interbreeding. Pacific and winter wrens, along with the Eurasian wren, look so similar that they were formerly considered to be the same species until studies of their DNA and vocalizations proved otherwise.1

Not only is the secretive winter wren nearly identical to the Pacific wren, but it’s also very similar to the Eurasian wren, the only wren species found outside the Americas. NICK CARTER

Marsh Wren and Sedge Wren

Not all wrens lurk in nooks and undergrowth. Two Alberta species prefer open meadows and wetlands. The far more common species is the marsh wren. True to its name, this is a bird of cattail marshes. From about late May to early October, most of Alberta east of the Rockies is home to this wren, which is best seen at any sizable wetland in the prairies and parkland.

In true wren fashion, the marsh wren is much easier to hear than it is to see. The body is rusty brown on top, paler below, with a white throat and breast. The bill is relatively long and down-curved. Noticeable streaks of black and white down the back and distinct white eyebrows make the marsh wren easy to tell apart from the species covered here so far, but it disappears remarkably well amidst dense, brown and green wetland plants.

The song of the marsh wren is a trilling, gurgling chatter. By keeping a patient watch on the source of this song, wetland birdwatchers can hope to catch a look at this pugnacious little wren as it confidently flits through the cattails or perches with legs splayed wide between two bulrush stems. The nest is a hollow ball of vegetation woven among the plant stems, and the marsh wren is so territorial that it will destroy the eggs and nestlings of other marsh wrens that breed nearby.

Similar in appearance and lifestyle to the marsh wren is the sedge wren. While it can be found in wetlands, the sedge wren favours long-grass fields and wet meadows. From a cursory glance in the field, a sedge wren can be hard to tell apart from a marsh wren. The sedge wren has a completely barred back as opposed to the plain rusty shoulders of the marsh wren. The brown stripe on the crown of the sedge wren’s head is streaked as opposed to solid, and the bill of the sedge wren is shorter than that of the marsh wren. The sedge wren differs in voice as well, giving off a few dry chirps followed by a short trill.

Sedge wrens are also more geographically restricted than marsh wrens, with the western extent of their range falling within east-central Alberta. They don’t stick around as late as marsh wrens, generally moving south in August.

Like so many other wetland birds, the marsh wren is much easier to hear than it is to see. It takes some patience to get a good look at this little acrobat among the cattails. NICK CARTER

Rock Wren

The rock wren makes its home in the dry prairie badlands and mountain cliffs of southern Alberta and nests in stony crooks and crevices. With its greyish-brown upper side and pale, finely streaked underside, this species blends in well with the rock exposures it lives on. The bill is long and downturned, well suited to prying insects and spiders out of their hiding places. The song of the rock wren, delivered with gusto from a stony perch, is a varied series of dry chirps and trills.

Rock wrens spend May through August in Alberta, but their specific habitat requirements make them relatively uncommon. The badlands of Dinosaur and Writing-on-Stone Provincial Parks are among the more reliable places to see this species.

Like an Alberta cowboy, the dusty little rock wren is at home in the prairie badlands and mountain slopes. NICK CARTER

Wren Wrap-Up

So that’s the rundown on wrens for you. While they might lack the majesty of larger birds like raptors or waterfowl, for those who appreciate the smaller things in nature, watching wrens brings no end of joy. These small, energetic songbirds are worth listening and watching for. Whether it be in the tangled forest brambles, an endless cattail maze, or the arid badlands, when the time is right, the wrens will be out there.

References

- Toews, D.P. and D.E. Irwin (2008). Cryptic speciation in a Holarctic passerine revealed by genetic and bioacoustic analyses. Molecular Ecology, 17(11), 2691–2705. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-294X.2008.03769.x

Nick Carter is a naturalist and science communicator from Edmonton and is Nature Alberta’s Nature Kids Coordinator. He studied biology at the University of Alberta and has had a lifelong fascination for all things in the natural world.

Read the Original Article for this Post

For a richer reading experience, view this article in the professionally designed online magazine with all images and graphs in place.

This article originally ran in the Spring 2025 issue of Nature Alberta Magazine (Vol. 55 | No. 1).