Beneath the Buzz: Alberta’s Native Bees as Nature’s Unsung Heroes

22 April 2024

BY MEGAN EVANS

While honey bees often steal the spotlight, it is our native bee species that quietly work as the unsung heroes of pollination across Alberta’s diverse landscapes. With 370 bee species native to our province, these small yet mighty insects play a vital role in the reproduction of flowering plants, including many of our agricultural crops and wildflowers.

Bee Diversity: Social and Solitary

You’re likely familiar with bumble bees — big, fuzzy, loud attention-grabbers! The life cycle of a bumble bee begins in early spring when a mated queen emerges from hibernation. She searches for a suitable nest site, often in underground burrows or abandoned rodent nests (or sometimes in your home’s insulation or under a step!). The queen then begins laying eggs, which emerge as adults in a few weeks. The newly emerged worker bumble bees take on various roles within the nest, such as foraging for nectar and pollen, constructing and expanding the nest, and caring for the brood. The queen continues to lay eggs, and the colony grows, ranging from a few dozen to several hundred individuals. Toward the end of the summer, the queen produces males and new queens, which leave the nest to mate with bees from other colonies. After mating, the males die, as do the founding queen and workers, and the newly mated queen finds a hibernation site to overwinter.

Despite their high profile, bumble bees aren’t the most common type of bee. There are only about 30 bumble bee species in Alberta and they account for less than 10% of Alberta’s total bee diversity. The other bees (340 species from six families and 38 genera) come in all shapes, sizes, and colours of the rainbow! We often refer to these bees as “solitary bees,” because the majority are truly solitary. But mixed in are some species that are social and live like bumble bees, with a queen and workers and so on, and others that nest in aggregations.

The life cycle of a typical solitary bee begins with the female bee finding a suitable nesting site. This can be a hollow plant stem, a hole in wood, or a tunnel she has excavated in the ground. Once the nesting site is chosen, the female bee collects pollen and nectar and creates a small provision mass. She lays a single egg on top of the provision mass and then seals it off with a partition made of mud, leaves, or other materials. This process is then repeated, with each provisioned cell containing a single egg. The female bee may construct several cells within her chosen nesting site. Each egg transitions from larvae to pupa within its nesting cell and the adult bee typically emerges the following year by chewing through the cell partition and exiting the nest. Adult females search for suitable nesting sites to continue the life cycle, while males focus on finding mates.

How Are Our Bees Doing?

We often hear about bee declines in the news, so you might wonder how our native bees are doing. In Alberta, about 30% of our native bees are secure or apparently secure, 10% are rare or declining, and, alarmingly, a whopping 60% are unrankable because we simply don’t have enough information to assess their status. Two species, the yellow-banded bumble bee (Bombus terricola) and gypsy cuckoo bumble bee (Bombus bohemicus), have been formally listed under the federal Species at Risk Act (as Special Concern and Endangered, respectfully).

The decline of native bees is attributed to several factors acting in combination, including habitat loss, pesticide exposure, climate change, and disease. As natural landscapes are converted into farmlands, cities, roads, and other modified habitats, native bee nesting sites and food resources are destroyed or become limited. Pesticides, even at low levels of exposure, can impair bee foraging abilities, navigation skills, and overall health. Neonicotinoids are a particular concern because they are typically applied as a seed coating prior to planting, which has led to widespread overuse. A more appropriate means of using these pesticides would be to monitor crops for signs of pests and apply them when early signs are detected. Climate-associated risks include rising temperatures, altered precipitation patterns, forest fires, and other extreme weather events. Such events impact bees directly and can also result in a mismatch between the emergence of bees and the availability of flowers for foraging. Existing and novel diseases (including those transmitted by honey bees) contribute to bee decline as well.

The decline of bees is part of a larger problem of insect declines, which are occurring across the world. Conservation efforts are crucial to halt and reverse these declines. Key measures include preserving and restoring habitats, reducing pesticide usage, promoting climate resilience, developing more stringent regulations pertaining to managed bees, and raising awareness about the importance of native bees.

Honey Bees

Honey bees are not native to North America. They were introduced to the continent by beekeepers, essentially as a managed livestock species. In addition to producing honey (and who doesn’t love honey!), they also play a crucial role in pollinating agricultural crops, and farmers rent hives for this purpose. Overwintering losses can be high — an estimated 50% loss was reported in 2022. However, the number of commercial honey bee colonies in Alberta has remained relatively stable (at over 300,000) despite these losses. In fact, through the import of expansion colonies, the number of honey bee hives in Alberta has doubled since the 1980s.

Unfortunately, the relationship between honey bees and native bees is not a positive one. Honey bees can compete for limited food resources and spread diseases. More research needs to be done to better understand these impacts and to implement mitigation measures, develop best practices, and limit the placement of honey bee colonies, particularly in areas where at-risk native bee species are present.

Long-horned bee (Melissodes) male on gumweed. SYDNEY WORTHY

Bee Conservation

The Alberta Native Bee Council (ANBC) was established in 2017 to address gaps in native bee conservation. We work to achieve healthy and resilient native bees and their habitats in Alberta. An initial step was to launch a collaborative, provincewide program to monitor native bees to better understand which species are present and how they’re doing. We’ve also developed some identification resources, created a citizen science bumble bee box monitoring program (read on for details on how to participate), developed best management practices to help protect our native bees, contributed to research on the status of native bees in Alberta, and contributed to recovery strategies for bees of concern in Alberta.

You can help make important contributions in conserving native bees. Here are some steps you can take:

- The best thing you can do for native bees is plant native flowers. Visit the ANBC website, albertanativebeecouncil.ca, for a list of native flower species that support native bees. If you can’t plant native flowers, plant ornamental varieties.

- Reduce or eliminate the use of pesticides and herbicides in your garden or property to protect bees from potentially harmful exposure.

- Incorporate diversity in your landscaping and gardening. Native bees can nest in decaying stumps, under piles of branches, in sandy spots, and in hollow stems. Providing nesting habitat for native bees is just as important as providing food!

- Build a bumble bee box and participate in our citizen science bumble bee box monitoring program. You’ll find instructions for building a bumble bee box on our website. You can also build a solitary bee hotel, but be sure to check out ANBC’s online guide before deciding on a design.

- Take up bee watching! You can watch bees right in your own backyard. If you’re keen, you can send pictures of bees to iNaturalist or bumblebeewatch.org.

- Raise awareness about the importance of native bees by sharing information with friends, family, and community members through social media and conversations.

- Get kids excited about bees and encourage learning by using ANBC’s downloadable resources for children.

- Understand that keeping honey bees does not support native bee conservation and may even harm native bees.

- Support the Alberta Native Bee Council, the Alberta Native Plant Council, or other grassroots non-profit organizations doing great work in Alberta by becoming a member or purchasing merchandise!

Identifying Bees

Bees come in all colours of the rainbow and vary from large, fuzzy bumble bees to teeny, relatively hairless sweat bees (see photos). It can sometimes be challenging to differentiate bees from other insects, but everyone can learn. A good first step is to learn to differentiate bees from flies, which can be tricky, especially when it comes to bee mimics. The key characteristics to look for are the eyes — fly eyes are much larger than bee eyes — and antennae — bees have long, jointed antennae whereas flies usually have short, stubby antennae. Also, all bees (and sometimes wasps and ants) have two sets of wings (four total). One set of wings are large forewings, and the other is a smaller set of hind wings. Flies only have a single set of wings.

In addition to physical differences, you can use behaviour to determine what kind of critter you’re looking at. Female bees will almost always be observed actively foraging for pollen and/or nectar on flowers. Some flies mimic bee colour patterns and are often confused with bees, but they exhibit very different behaviours. For example, robber flies won’t be found foraging for pollen and nectar, and hoverflies have a distinct hovering flight pattern.

You can learn more about bees on the Alberta Native Bee Council website, albertanativebeecouncil.ca. Start your journey into the world of native bees today by planning a bee safari anywhere that flowers are blooming!

Megan Evans is a terrestrial ecologist with over ten years in the field. She is passionate about protecting biodiversity, especially our native plants and pollinators. She contributes to those efforts through her work as the Executive Director of the Alberta Invasive Species Council and President of the Alberta Native Bee Council.

Read the Original Article for this Post

For a richer reading experience, view this article in the professionally designed online magazine with all images and graphs in place.

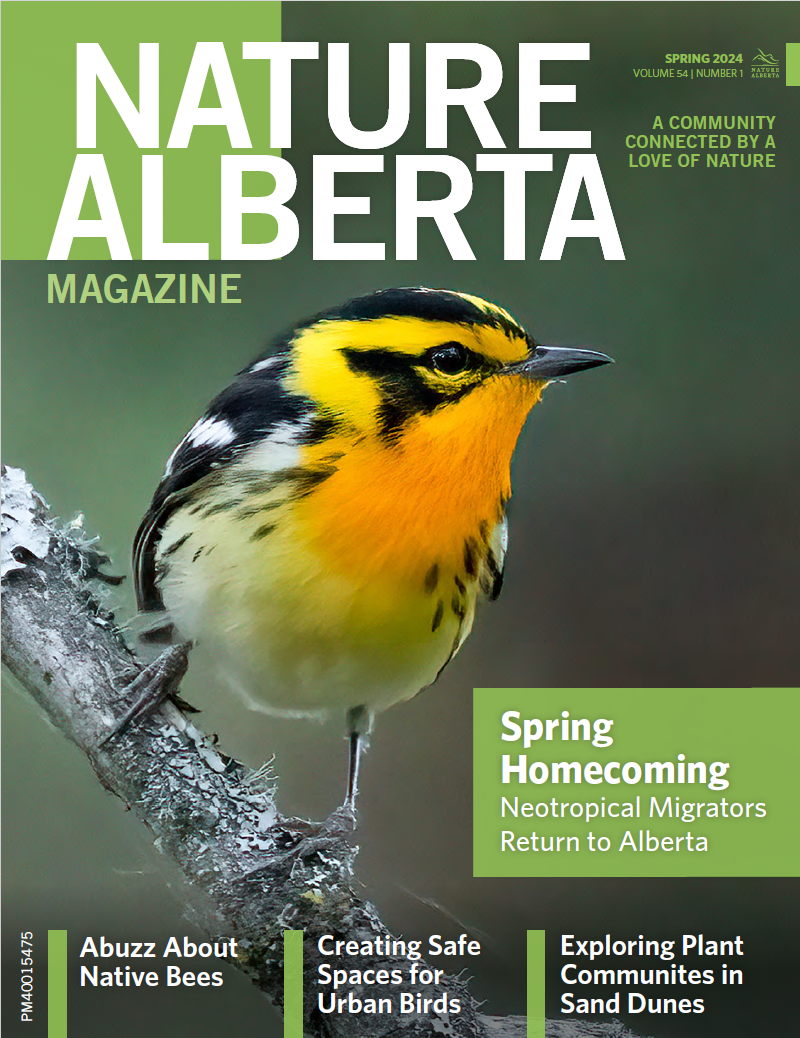

This article originally ran in the Spring 2024 issue of Nature Alberta Magazine (Vol. 54 | No. 1).