The Birds of Alberta, A Century Ago

5 July 2024

BY JOHN ACORN, FAUVE BLANCHARD, AND MELANIE MULLIN

Have you ever wondered what the birdlife of Alberta was like a century ago? Some published information exists, but there was a period during the early 1900s when very little was being written about the changing status of Alberta birds. Not only that, little or no attempt was being made to merge mainstream science with Indigenous people’s traditional ecological knowledge. So we know a lot less about the so-called original state of local birdlife than perhaps we think we do.

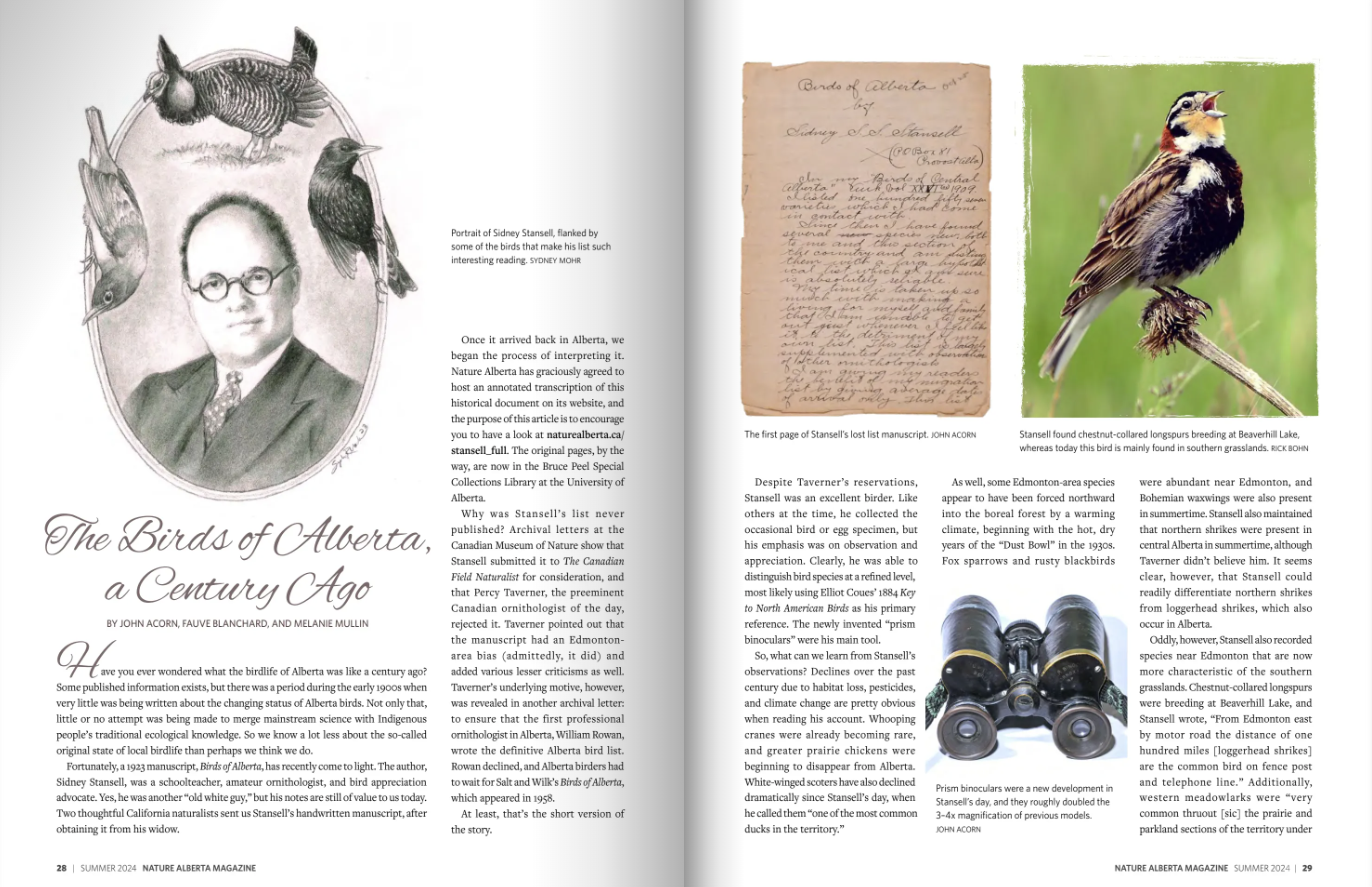

Fortunately, a 1923 manuscript, Birds of Alberta, has recently come to light. The author, Sidney Stansell, was a schoolteacher, amateur ornithologist, and bird appreciation advocate. Yes, he was another “old white guy,” but his notes are still of value to us today. Two thoughtful California naturalists sent us Stansell’s handwritten manuscript, after obtaining it from his widow.

Once it arrived back in Alberta, we began the process of interpreting it. Nature Alberta has graciously agreed to host an annotated transcription of this historical document on its website, and the purpose of this article is to encourage you to have a look at naturealberta.ca/stansell_full. The original pages, by the way, are now in the Bruce Peel Special Collections Library at the University of Alberta.

Why was Stansell’s list never published? Archival letters at the Canadian Museum of Nature show that Stansell submitted it to The Canadian Field Naturalist for consideration, and that Percy Taverner, the preeminent Canadian ornithologist of the day, rejected it. Taverner pointed out that the manuscript had an Edmonton-area bias (admittedly, it did) and added various lesser criticisms as well. Taverner’s underlying motive, however, was revealed in another archival letter: to ensure that the first professional ornithologist in Alberta, William Rowan, wrote the definitive Alberta bird list. Rowan declined, and Alberta birders had to wait for Salt and Wilk’s Birds of Alberta, which appeared in 1958.

At least that’s the short version of the story.

Despite Taverner’s reservations, Stansell was an excellent birder. Like others at the time, he collected the occasional bird or egg specimen, but his emphasis was on observation and appreciation. Clearly, he was able to distinguish bird species at a refined level, most likely using Elliot Coues’ 1884 Key to North American Birds as his primary reference. The newly invented “prism binoculars” were his main tool.

So, what can we learn from Stansell’s observations? Declines over the past century, due to habitat loss, pesticides, and climate change, are pretty obvious when reading his account. Whooping cranes were already becoming rare, and greater prairie chickens were beginning to disappear from Alberta. White-winged scoters have also declined dramatically since Stansell’s day, when he called them “one of the most common ducks in the territory.”

As well, some Edmonton-area species appear to have been forced northward into the boreal forest by a warming climate, beginning with the hot, dry years of the “Dust Bowl” in the 1930s. Fox sparrows and rusty blackbirds were abundant near Edmonton, and Bohemian waxwings were also present in summertime. Stansell also maintained that northern shrikes were present in central Alberta in summertime, although Taverner didn’t believe him. It seems clear, however, that Stansell could readily differentiate northern shrikes from loggerhead shrikes, which also occur in Alberta.

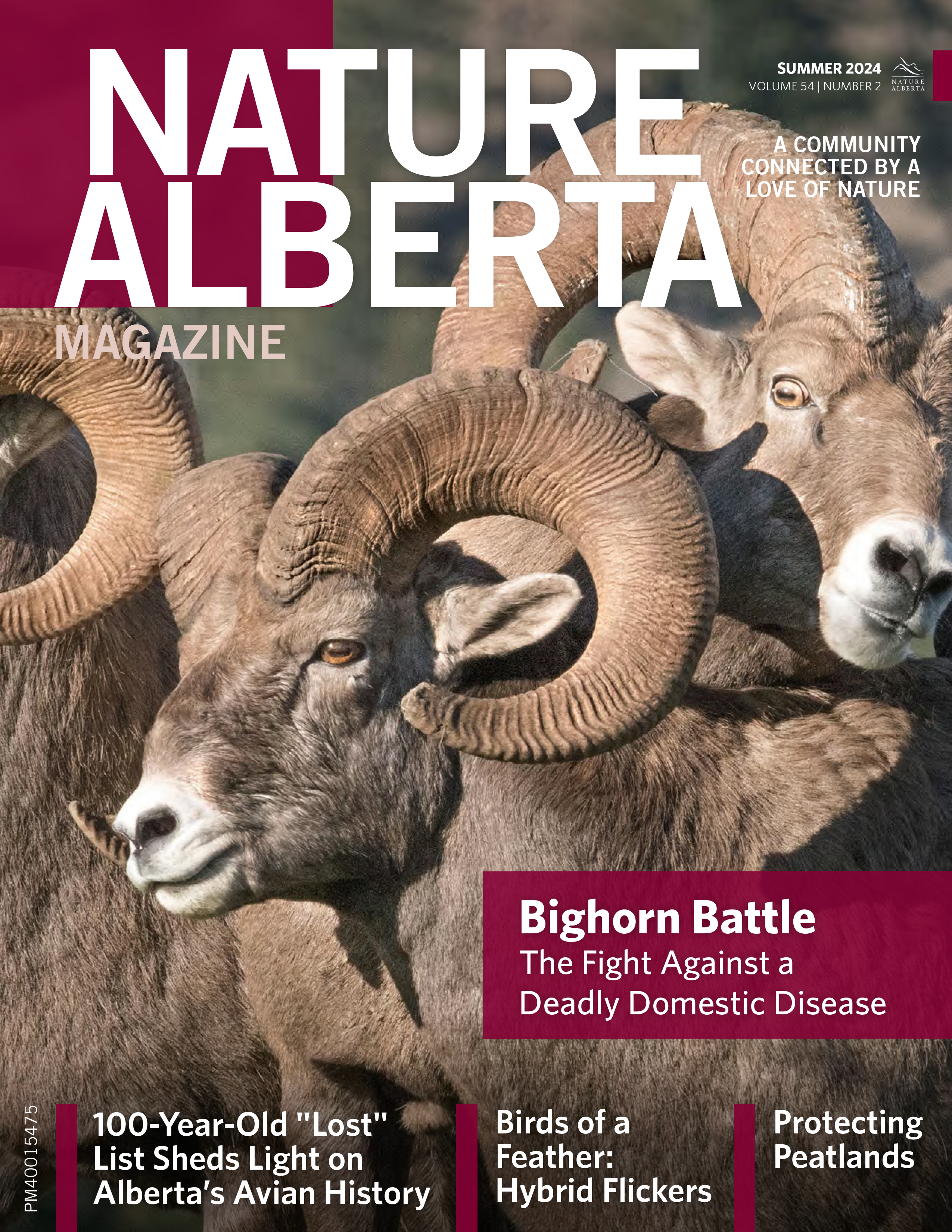

Oddly, however, Stansell also recorded species near Edmonton that are now more characteristic of the southern grasslands. Chestnut-collared longspurs were breeding at Beaverhill Lake, and Stansell wrote, “From Edmonton east by motor road the distance of one hundred miles [loggerhead shrikes] are the common bird on fence post and telephone line.” Additionally, western meadowlarks were “very common thruout [sic] the prairie and parkland sections of the territory under consideration and often met within the timbered sections.”

What to make of this? Frequent fires and a more open landscape might be the explanation, but really, who knows?

Surprisingly, Stansell’s list also includes many species that have subsequently increased in number. In 16 years of observation, he encountered no swans, no greater white-fronted geese, and no semipalmated plovers, and neither prairie nor peregrine falcons. Of course, one person’s observations can easily miss particular species, and every birder has had their “jinx birds.” But still...

In Stansell’s account, there are no white-breasted nuthatches, and red-breasted nuthatches had only recently become “fairly common.” Purple martins were uncommon before martin houses became popular, and Stansell lamented, “After looking over a large part of Alberta for this species year after year, I finally located a colony in the spring of 1915 about one hundred miles northwest of Edmonton in a semi-open woodland.”

Perhaps most puzzling is the magpie hiatus. During the first two decades of the 20th century there were apparently no magpies at all in central Alberta, despite evidence that they had been abundant here in the 1800s. Why the gap? The disappearance of the bison? An epidemic such as avian flu? Perhaps we will never know, or perhaps we haven’t yet tried to answer the question.

We find Stansell’s account both believable and ecologically humbling. Ornithologists have developed a pretty good understanding of recent trends in bird distributions and abundances, but the situation a century ago doesn’t seem like a perfect fit for our current narratives.

The point of this article is not, however, to solve these riddles, or to provide definitive interpretations of Stansell’s observations. Stansell’s manuscript gives additional clues, and we hope that our annotations add a few more. Ultimately, though, the Stansell manuscript is just one of many sources of information about historical changes in the birdlife of our province.

Stansell’s legacy extends beyond his manuscript. In 1923, he left Alberta for California, where he continued teaching, earned a master’s degree in education, and became a public speaker, delivering over 400 talks illustrated by his own photographs, presented as “lantern slides.” These talks highlighted the birds of Alberta, providing a captivating glimpse into a world that many Californians could only imagine. A summary of Stansell’s published contributions to Alberta ornithology can be found in a 1996 article in Alberta Naturalist written by Holroyd and Palaschuk.1

The avian history of Alberta is complicated, blending themes of resilience, loss, adaptation, and mystery. The rediscovery of Stansell’s manuscript invites us to reevaluate our understanding of Alberta birdlife, reminding us that the past holds valuable lessons for the future. Stansell’s work invites all bird enthusiasts to explore and appreciate new details in the still-unfolding story of Alberta's avian past.

Sidney Stansell’s Lost List: The Birds of Alberta, as of 1923

Read this remarkable look into Alberta’s natural history, introduced and annotated by John Acorn, Fauve Blanchard, and Melanie Mullin, online at naturealberta.ca/stansell_full

References

- Holroyd, G.L. and C. Palaschuk (1996). Sidney S.S. Stansell, Alberta’s First Christmas Bird Counter. Alberta Naturalist, Volume 26, Number 2. Available at edmontonchristmasbirdcount.ca/library.html

John Acorn is a naturalist and conservation biologist. He teaches at the University of Alberta and proudly serves as Patron of Nature Alberta.

Fauve Blanchard studied at the University of Alberta and currently works as a government wildlife biologist out of Whitecourt, Alberta.

Melanie Mullin was born in Quebec, completed B.Sc. and M.Sc. degrees at the University of Alberta, and currently works as a physical scientist for Environment and Climate Change out of Ottawa, Ontario.

Read the Original Article for this Post

For a richer reading experience, view this article in the professionally designed online magazine with all images and graphs in place.

This article originally ran in the Summer 2024 issue of Nature Alberta Magazine (Vol. 54 | No. 2).