Dark Secrets: Discovering the Unusual Habits of the Black Swift

18 October 2024

By GEOFF HOLROYD

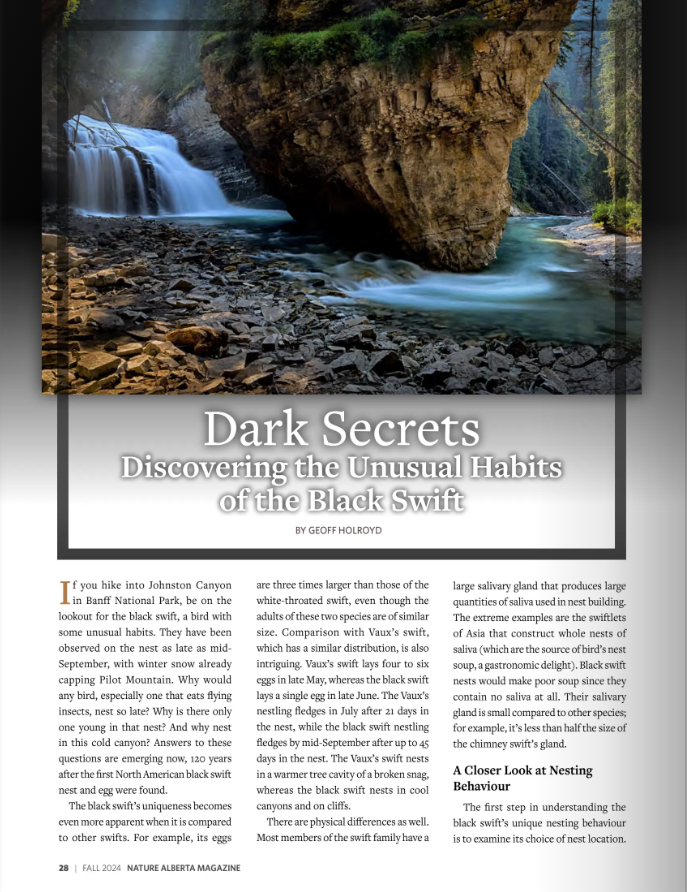

If you hike into Johnston Canyon in Banff National Park, be on the lookout for the black swift, a bird with some unusual habits. They have been observed on the nest as late as mid-September, with winter snow already capping Pilot Mountain. Why would any bird, especially one that eats flying insects, nest so late? Why is there only one young in that nest? And why nest in this cold canyon? Answers to these questions are emerging now, 120 years after the first North American black swift nest and egg were found.

The black swift’s uniqueness becomes even more apparent when it is compared to other swifts. For example, its eggs are three times larger than those of the white-throated swift, even though the adults of these two species are of similar size. Comparison with Vaux’s swift, which has a similar distribution, is also intriguing. Vaux’s swift lays four to six eggs in late May, whereas the black swift lays a single egg in late June. The Vaux’s nestling fledges in July after 21 days in the nest, while the black swift nestling fledges by mid-September after up to 45 days in the nest. The Vaux’s swift nests in a warmer tree cavity of a broken snag, whereas the black swift nests in cool canyons and on cliffs.

There are physical differences as well. Most members of the swift family have a large salivary gland that produces large quantities of saliva used in nest building. The extreme examples are the swiftlets of Asia that construct whole nests of saliva (which are the source of bird’s nest soup, a gastronomic delight). Black swift nests would make poor soup since they contain no saliva at all. Their salivary gland is small compared to other species; for example, it’s less than half the size of the chimney swift’s gland.

A Closer Look at Nesting Behaviour

The first step in understanding the black swift’s unique nesting behaviour is to examine its choice of nest location. A top priority is keeping the nest contents safe from terrestrial predators. All nests discovered to date have been on sea or mountain cliffs, in canyons, and in caves — places inaccessible to mammals.

Swifts select nest sites that are high above the local terrain with an unobstructed flight path. This is necessary because swifts fly at relatively high speeds and are not adept at manoeuvring through forests. They also benefit from the flight advantage that comes with nesting on cliffs, where the drop from their nest allows them to gain flight speed, compensating for their relatively small chest muscles.

Black swift nests are located near moving water. All the documented nests are over a stream, beneath a waterfall, or above the sea. The advantage here is not as clear. Does the water noise drown out any begging noise from the young that might attract a predator? In Johnston and Maligne Canyons in the Alberta Rockies, the nest ledges are near waterfalls, so close to the spray zone that green moss grows below the nest, fertilized by the droppings of the young and adults. Photographer Tom Ulrich observed the young reaching for drops of water. Do wet sites help keep the young hydrated?

Most curious, though, is the requirement that the nest be located so that the sun does not shine on it! Warm, south-facing, sunny cliffs are shunned in favor of cool, north-facing cliffs. Why would the swifts not choose a warm nest site for their young, especially in the mountains where warmer locations are still relatively cool?

Young black swifts are well equipped to deal with their cold, wet environments. Although they hatch naked, the young quickly develop an extensive downy plumage before growing their adult plumage. These new feathers erupt from their sheaths by the eighth or ninth day and cover the nestling by day 19. Downy plumage is not found in other swifts, except for some closely related species in the genus Cypseloides.

A young black swift, right, eagerly receiving its meal after waiting as long as a full day since its last one. TOM ULRICH

Investigating the Mysteries

My interest in black swifts began in 1975, when two friends showed me a nest in Johnston Canyon. I returned annually for 43 years to count the nests on the accessible cliffs that are visible from the nature trail. The number of swifts varied from seven to 13 pairs until 1993. But the next year, the number of occupied nests dropped significantly and there have been only two to four nests since then. Why the number dropped so dramatically is still unknown.

In 1982 and 1983, I visited the canyon weekly to collect droppings beneath a few nests that were not built directly over the stream. Droppings from these nests fell on rocks where I could scoop up the fecal matter. These droppings contained digested but identifiable insect parts that provided clues to explain the strange breeding behavior of the black swift.

In early summer, the black swifts eat flies, beetles, and other insects, similar to the diet of swallows. There are no young until later July, so these droppings are all from the adults. In August and early September, when most droppings are from juvenile swifts, carpenter ants dominate the diet. These ants disperse in swarms in late summer to establish new colonies. Flying ants are a very desirable food since they are 40% fat and 7% glycogen — approximately six times the energy content per gram of flies. Although ants are a highly energy-rich food source, they are widely dispersed. This requires long searches, but the swifts are suited for such long flights.

Observations from Vancouver provide evidence of the long-distance flying ability of black swifts in the breeding season. While nesting in mountains to the east, up to 1,000 black swifts have been observed on the southern British Columbia coast. They make this journey to avoid cool, wet weather, which occurs when low pressure systems from the Pacific Ocean pull cool air from the north behind them. The black swifts leave the mountains and fly south into the warm air, where insects are likely to be more abundant. Once the cool front passes, they return north. In Europe, such flights extend up to 1,600 km over three days before the cool weather passes and the European swifts return to their nests.

Because the parents must forage widely for dispersed food, the chick is only fed infrequently, typically daily in the evening when both parents return. Occasionally the adults will return during the day to feed the young chick, but most days the youngster is left alone. The relative inaccessibility of the nest site provides some security, though the chick may still be vulnerable to aerial predators. While the chick waits for this infrequent feeding, it must conserve valuable nutrients and energy. This explains why the nestling takes 45 days to grow and fledge, considerably longer than other similar-sized birds. It may also explain why black swifts raise a single young rather than many.

Infrequent feeding may even be the reason swifts choose a cool nest site. It’s possible that a cool environment may facilitate torpor in the young while the adults are away. In other words, the young conserve energy by lowering their temperature and metabolism. This strategy would be similar to that of alcid seabirds, which also typically raise a single young that matures slowly. Like black swifts, these seabirds forage for dispersed prey far from the nest and require a nesting strategy designed to cope with infrequent feeding. Adult swifts are known to use torpor to cope with inclement weather and lack of insect food.

Species that have a slow rate of reproduction are generally believed to be long-lived. This appears to be the case for black swifts, since researchers from the Bird Conservancy of the Rockies in Colorado caught a female swift in August 2023 that they had banded as an adult at the same nest in 2005, making the swift at least 19 years old!

Looking Forward

Black swifts continue to intrigue me. So many questions remain to be answered! If in fact the young do become torpid to save energy, this implies that the adults are purposely selecting a cool nest site. This would be highly unusual. In other species where torpor has been studied, it is used by birds to cope with cold and lack of food, not, as seems to be the case here, to save energy while harvesting a dispersed food source.

When my son Michael was ten days old, I took him to see the black swifts in Johnston Canyon. Ten years later, he was the first to find a nest in Maligne Canyon in Jasper National Park. Will he be able to show his children black swifts?

The black swift has received little popular press. The inaccessible nest sites provide security for the young but make monitoring the population difficult. What does the future hold for this species? How do the various ant species that make up their young’s diet react to the clear-cutting practices of North American forestry and to large expanses of burned trees? These and other questions need to be answered to gain a better understanding of black swift’s biology. As we search for more clues to the ecology of the black swifts, we must also ensure that we protect their remote nest sites.

Geoff Holroyd is a retired research scientist with Canadian Wildlife Service and Environment and Climate Change Canada, and a retired adjunct professor at the University of Alberta. He is currently chair of the Beaverhill Bird Observatory. He monitored black swifts in Johnston Canyon for over 40 years and documented their diet in the 1980s.

Read the Original Article for this Post

For a richer reading experience, view this article in the professionally designed online magazine with all images and graphs in place.

This article originally ran in the Fall 2024 issue of Nature Alberta Magazine (Vol. 54 | No. 3).