Don’t Mine McClelland

BY PHILLIP MEINTZER, AWA Conservation Specialist

If you drive north from Fort McMurray for about an hour along Highway 63, you’ll reach one of Alberta’s greatest, but also lesser-known natural treasures—one that’s at risk of destruction.

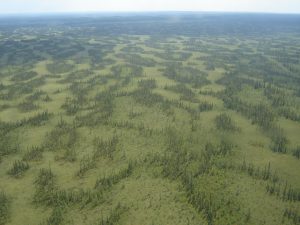

The McClelland Lake Wetland Complex is a large wetland area near the confluence of the Firebag and Athabasca Rivers. The complex is dominated by peatlands, and features a beautiful and provincially significant patterned fen, with its characteristic string and flark topography (alternating peat ridges and shallow-water depressions). It has formed over the past eight to 11 thousand years, and has 12 sinkhole lakes, plus McClelland Lake itself.

Peatlands, such as the patterned fen found at the McClelland Lake Wetland Complex are critical for preventing and mitigating climate change, as well as filtering and protecting freshwater. Peatlands occupy only three percent of Earth’s terrestrial surface area but store a staggering 30 percent of all land- based carbon. This means that peatlands are the best terrestrial carbon storage we have available to us, and one of the strongest tools we have at our disposal for preventing the worst impacts of climate change.

Photo Credit: J. Hildebrand

Intact peatlands not only serve as carbon storage but also act as a carbon sink by taking carbon from the atmosphere and storing it in plants and soil. Estimates suggest that the McClelland area may store up to 9.7 million tonnes of carbon, which is equivalent to nearly 35.5 million tonnes of released carbon dioxide. That’s more than the total emissions from the province of Manitoba in a single year based on 2021 data. Recent evidence also suggests that peatlands serve as a crucial buffer zone that minimizes the impact of wildfires on neighboring ecosystems, which is important as climate change makes wildfires more frequent and severe.

Reports indicate that the wetland complex supports at least 18 species of provincially rare mosses and hepatics (or liverworts). According to the Alberta Native Plant Council, other rare plants documented in the area include dragon’s mouth, few seeded sedge and the orchid known as stemless lady’s slipper. Dragon’s mouth is categorized as an S1 species in Alberta which means that there are fewer than five documented occurrences in the province.

The area is also an important socio-cultural site for Indigenous communities in the region for traditional and cultural practices such as harvesting foods and medicines. Some of the important plant species harvested by Indigenous Peoples include balsam, tamarac, birch, sweetgrass, red willow, diamond willow fungus, saskatoon berries, pin cherries, blueberries, and low-bush cranberries.

The McClelland Lake Wetland Complex sits directly within a major North American migratory bird flyway. 205 bird species have been recorded within the area, of which 116 are known to stay and breed. The wetland complex provides a nursery for birds such as bald eagles and sandhill cranes, and it serves as a stopover point for endangered whooping cranes en route to their breeding grounds further north, although they do not nest in the area. Four other at-risk bird species are known to frequent the complex including olive-sided flycatchers, common nighthawks , and the region is the most significant wetland for confirmed counts of rusty blackbirds and yellow rails. The latter two are listed as “Special Concern” under Canada’s Species at Risk Act (SARA).

Photo Credit: C. Wearmouth

The McClelland area is also a hot spot for boreal wildlife, including at risk species, such as threatened woodland caribou. It is home to woodland frogs and Canadian toads, and four species of fish inhabit McClelland Lake and the surrounding watershed.

In 1996, the wetland complex was placed off-limits to oil sands mining within the approved Fort McMurray-Athabasca Oil Sands Subregional Integrated Resource Plan (IRP). Again, in 1999, the Alberta Special Places 2000 Committee nominated the complex for a protective notation as an environmentally significant area, which was intended to ensure that the area would be managed for conservation.

However, after the discovery of oilsands bitumen reserves underneath the MLWC, the sub-regional planning rules suddenly changed in 2002 at the request of True North Energy (a subsidiary of Koch Industries), which had been allowed to acquire leases for the area in 1998 despite the existing protections for the area.

At the 2002 Fort Hills mine application hearing, regulators allowed True North Energy to set aside the Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) that was part of their application. This EIA had stated that water table disruptions from mine dewatering and other lease disturbances would likely kill peat-forming mosses, ending peat production on the fen. Subsequently, the 2002 Energy and Utilities Board Decision Report permitted mining in roughly half of the wetland complex so long as the ecological diversity and functionality of the unmined portion is maintained.

Suncor Energy is now the majority owner of the Fort Hills mine, and it was required to develop and submit a mitigation plan (known as the Operational Plan) to demonstrate how it will protect the unmined area from the impacts of mining, which includes a nearly 14-kilometre-long underground wall to split the wetland in two. This mitigation plan was unfortunately approved by the Alberta Energy Regulator (AER) in September 2022; however, a recent report produced by the Alberta Wilderness Association (AWA), and conducted by Dr. Lorna Harris, with Wildlife Conservation Society Canada, and Dr. Kelly Biagi, an assistant professor at Brock University, raised several concerns with Suncor’s plan: it poses a significant risk of irreversible damage to the unmined area.

AWA’s assessment found that Suncor’s plan failed to account for the potential saline (or salt) contamination of freshwater, which is an issue that has been documented with other oil sands mining and reclamation projects. Saline-contaminated groundwater can have unintended consequences for the above-ground ecosystems, as it moves to the surface, impacting vegetation that has evolved over thousands of years in a purely freshwater environment. The report also found a lack of adequate modeling for potential impacts to groundwater quality and flawed assumptions that predicted water level changes will have negligible impacts. As well, Suncor’s proposed water management system relies on the underground wall, wells, pumps, and pipelines to work flawlessly for decades to prevent an ecological disaster. This is a first-of-its-kind experiment that's never been attempted anywhere else in the world. It’s a high-risk gamble with potentially catastrophic consequences for an important wetland ecosystem. The plan is by no means a guarantee of protection.

Photo Credit: S. Bray

AWA submitted an advanced copy of this report to the Alberta Energy Regulator (AER) on March 31, 2023, requesting that the AER reconsider and revoke its approval of Suncor’s Operational Plan pursuant to section 42 of the Responsible Energy Development Act (REDA). Under this legislation, AER may, in its sole discretion, reconsider its decision and may confirm, vary, suspend, or revoke the decision.

AWA was pleased to learn that the submission of this report resulted in the AER opening a Reconsideration Process for its decision to approve Suncor’s Operational Plan. Phase 1 of this Reconsideration Process has recently concluded, which encompassed submissions from both AWA as well as reply submissions from Suncor.

AWA’s final reply submission, delivered to the AER on June 9, 2023, contained compelling new information from three prominent wetland experts — Richard Lindsay, University of East London, U.K.; Dr. R. Kelman Wieder, Villanova University Pennsylvania; and Dr. David Locky, MacEwan University, Alberta—following their review of Suncor’s plan.

In the opinion of these three experts, the approved Operational Plan contains many significant gaps, which — if left unaddressed — pose a significant risk to the ecological diversity and function of the unmined wetland complex. These concerns include no testing of Suncor’s proposed wall and mitigation measures, a compromised vegetation monitoring program, and ignorance towards potential catastrophic changes from mining activities and mitigation failures. This compelling new information, alongside the previously submitted report, should lead the AER to reconsider and revoke their approval of Suncor’s Operational Plan.

Currently, there is no timeline provided for when the AER will make its decision on whether to proceed with Phase 2 of the Reconsideration Process. Right now, all we can do is wait and hope for the best. For the sake of our climate, biodiversity, and reconciliation with Indigenous Peoples, the McClelland Lake Wetland Complex cannot be destroyed.