A Grebe in Need

5 July 2024

BY NICK CARTER

Alberta’s grebes are a small but diverse family, including the shy pied-billed grebe, the handsome horned and eared grebes, and the theatrical red-necked grebe. We also have the western grebe and its close relative, Clark’s grebe, which I consider to be the two most elegant species. This article focuses on the western grebe, which is found throughout most of Alberta, but has shown a concerning population decline in recent decades.

Natural History

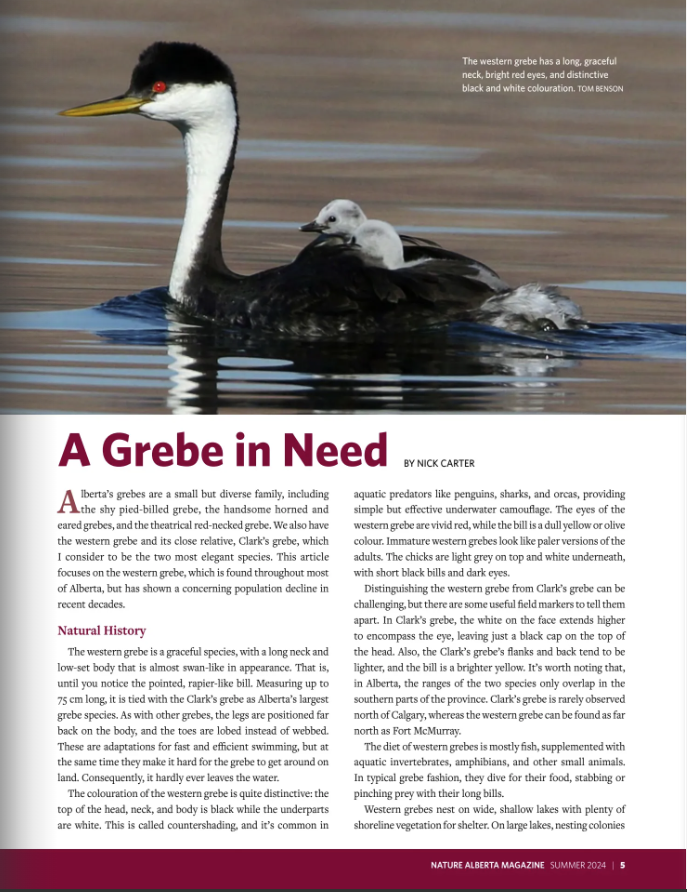

The western grebe is a graceful species, with a long neck and low-set body that is almost swan-like in appearance. That is, until you notice the pointed, rapier-like bill. Measuring up to 75 cm long, it is tied with the Clark’s grebe as Alberta’s largest grebe species. As with other grebes, the legs are positioned far back on the body, and the toes are lobed instead of webbed. These are adaptations for fast and efficient swimming, but at the same time they make it hard for the grebe to get around on land. Consequently, it hardly ever leaves the water.

The colouration of the western grebe is quite distinctive: the top of the head, neck, and body is black while the underparts are white. This is called countershading, and it’s common in aquatic predators like penguins, sharks, and orcas, providing simple but effective underwater camouflage. The eyes of the western grebe are vivid red, while the bill is a dull yellow or olive colour. Immature western grebes look like paler versions of the adults. The chicks are light grey on top and white underneath, with short black bills and dark eyes.

Distinguishing the western grebe from its close relative, Clark’s grebe, can be challenging, but there are some useful field markers to tell them apart. In Clark’s grebe, the white on the face extends higher to encompass the eye, leaving just a black cap on the top of the head. Also, the Clark’s grebe’s flanks and back tend to be lighter, and the bill is a brighter yellow. It’s worth noting that, in Alberta, the ranges of the two species only overlap in the southern parts of the province. Clark’s grebe is rarely observed north of Calgary, whereas the western grebe can be found as far north as Fort McMurray.

The diet of western grebes is mostly fish, supplemented with aquatic invertebrates, amphibians, and other small animals. In typical grebe fashion, they dive for their food, stabbing or pinching prey with their long bills.

Western grebes nest on wide, shallow lakes with plenty of shoreline vegetation for shelter. On large lakes, nesting colonies may contain hundreds of birds (though such colonies are increasingly rare). They make their nests out of plant matter, with a middle depression where two or three pale blue eggs are laid. After about three weeks, the young hatch and spend the early part of their lives riding on their parents’ backs until they’re old enough to swim on their own.

Social behaviours in western grebes, especially those involving courtship rituals, are as complex as they are beautiful. While normally a silent species, breeding grebe pairs call early in the season with a shrill cree creet sound while posturing to each other. The graceful “rushing ceremony,” done either between competing males or a breeding male and female, involves the two birds practically running side-by-side across the water’s surface, wings and neck held stiffly upright (visit bit.ly/western-grebe-rushing to watch this in action). The “weed ceremony” occurs later in the breeding season after the nest is built, and is strictly between a mated pair. This complex behaviour involves the pair posing and dancing in the water together, each holding a clump of aquatic vegetation in their beak. Lastly, there’s a “greeting ceremony,” done after a pair reunites after being separated, consisting of more laid-back versions of the behaviours seen in the other two ceremonies.

During migration, western grebes gather on large lakes, sometimes in massive numbers. Migration is just about the only time they fly, and it happens at night. Western grebes winter on or near the Pacific coast, along shorelines, sheltered bays, and estuaries. Depending on the conditions, a few may overwinter in Alberta where enough open water persists.

Population Declines

Western grebes have experienced a slow but steady decline over several decades, and much this seems to be due to human lakeside developments. As far back as 1958, in the first edition of The Birds of Alberta, Salt and Wilk stated that “of all species of grebes, the western grebe has suffered most from the advance of civilization in Alberta; most of the large lakes formerly frequented by nesting colonies are now popular vacation resorts, and unlike the red-necked grebe, the western grebe appears unable to adjust itself to the disturbance of the reveler and his motor-boat.”1

Surveys undertaken in the early 2000s indicated that major colonial nesting sites had been reduced to only a small number of lakes in the province.2 A status report in 2006 noted declines both in reproductive success and overall population size, especially in central and northeastern Alberta.2 Habitat degradation and disturbance by humans, pollution, and loss of prey availability were listed as the main threats to the species. The report recommended protecting and restoring western grebe habitat and called for additional research and public education.

An update report in 2012 found that out of 26 lakes in Alberta that had once supported large nesting colonies of western grebes, 13 no longer did.3 This represents an alarming loss of half of Alberta’s large western grebe colonies. Grebe counts from 2008 to 2011 found a total of only 9,549 birds, compared with 13,316 reported in 2006 — a 28% decrease. Consequently, in 2015 the Alberta government downgraded the status of the western grebe from “Sensitive” to “Threatened,” and it remains so today. Meanwhile, nationally important lakes for western grebe populations such as Wabamun Lake, Lac St. Anne, Lac La Biche, and Lesser Slave Lake are all still popular summer attractions for boaters, campers, and cottagers.

In a bit of good news, a 2018 status reassessment found evidence of western grebes nesting on several lakes in the Peace River Parkland — an area that had not been previously studied. This suggests that the breeding habitat for western grebes is likely more widespread than previously realized.4 I’ve observed western grebes on Bear Lake, a large, quiet waterbody just west of Grande Prairie, several years in a row.

With the inclusion of new breeding records from across the province, the current population may exceed 19,000 adults,5 which is nice to hear, but the loss of large breeding colonies remains a serious concern. Western grebes are highly vulnerable to habitat loss, human-caused accidents and disturbances, and reduction in the availability of food. These threats are also present on their west coast wintering grounds.

Conservation

In 2021, the Alberta Government released its recovery plan for the western grebe.5 The key strategies include research into habitat suitability and grebe biology, improved monitoring, and the protection of important nesting habitat. The plan also calls for public education about the sensitive nature of the species and the reduction of grebe mortality related to human activities.

Given that we have known since the 1950s that the western grebe is a vulnerable species, the recovery plan is arguably late in coming. Contrast this with the trumpeter swan, which has been closely monitored in Alberta for the past century and has had a recovery plan since 2012. Nevertheless, it is good that the recovery plan for the western grebe is now in place. It’s too soon to know what the long-term effectiveness of the plan will be, but the important thing is that action is being taken.

Securing the western grebe is something that all Albertans can and should have a hand in. Birdwatchers encountering western grebes would do well to submit their sightings to digital platforms like eBird and iNaturalist, especially during the breeding season. This will help biologists better understand the bird’s distribution across the province.

More than anything else, the western grebe needs plenty of wide, weedy lakes to live on, and the fewer people frequenting these lakes, the better. Albertans can support this by engaging in quiet and non-disruptive recreation on lakes frequented by western grebes, leaving the motorboats and barbecues to already-established resorts. We can also take action to oppose commercial and industrial activities near important western grebe habitat.

Securing the western grebe in Alberta by protecting the ecological integrity of our lakes will also have positive effects for all the other species that live in such places, from insects and fish to frogs and birds, and more. It’s a good reminder of how things in nature are connected to each other. And those of us who care about such things will be happy knowing there’s still some wilderness in Alberta for this regal bird of the west.

References

- Salt, W.R. and A.L. Wilk (1958). The Birds of Alberta. Department of Economic Affairs, Edmonton, AB.

- Alberta Sustainable Resource Development and Alberta Conservation Association (2006). Status of the Western Grebe (Aechmorphorus occidentalis) in Alberta. Alberta Environment and Sustainable Resource Development, Alberta Species at Risk Recovery Plan No. 60.

- Alberta Sustainable Resource Development and Alberta Conservation Association (2013). Status of the Western Grebe (Aechmorphorus occidentalis) in Alberta: Update 2012. Alberta Environment and Sustainable Resource Development, Alberta Species at Risk Recovery Plan No. 60.

- Prescott, D.R.C., J. Unruh, S. Morris-Yasinski and M. Wells (2018). Distribution and abundance of the western grebe (Aechmophorus occidentalis) in Alberta: an update. Alberta Environment and Sustainable Resource Development, Fish and Wildlife Policy Branch, Alberta Species at Risk Report No. 160, Edmonton, AB. 23 pp.

- Alberta Environment and Parks (2021). Alberta western grebe recovery plan. Alberta Species at Risk Recovery Plan No. 40. Edmonton, AB. 32 pp.

Nick Carter is a writer, photographer, and naturalist from Edmonton. From birds and bugs to flowers and fossils, Nick is always seeking out the natural wonders of this province and sharing his enthusiasm with others.

Read the Original Article for this Post

For a richer reading experience, view this article in the professionally designed online magazine with all images and graphs in place.

This article originally ran in the Summer 2024 issue of Nature Alberta Magazine (Vol. 54 | No. 2).