Motus: The Latest Advance in Tracking Bird Migration

19 January 2024

BY GEOFF HOLROYD and ETHAN DENTON

A new technology is allowing us to track small birds, bats, and even insects as they move around the world. It goes by the name Motus, which means “movement” in Latin. The Beaverhill Bird Observatory (BBO) has started using this new approach to track northern saw-whet owls, with exciting early results that we are pleased to share in this article.

The Evolution of Bird Tracking

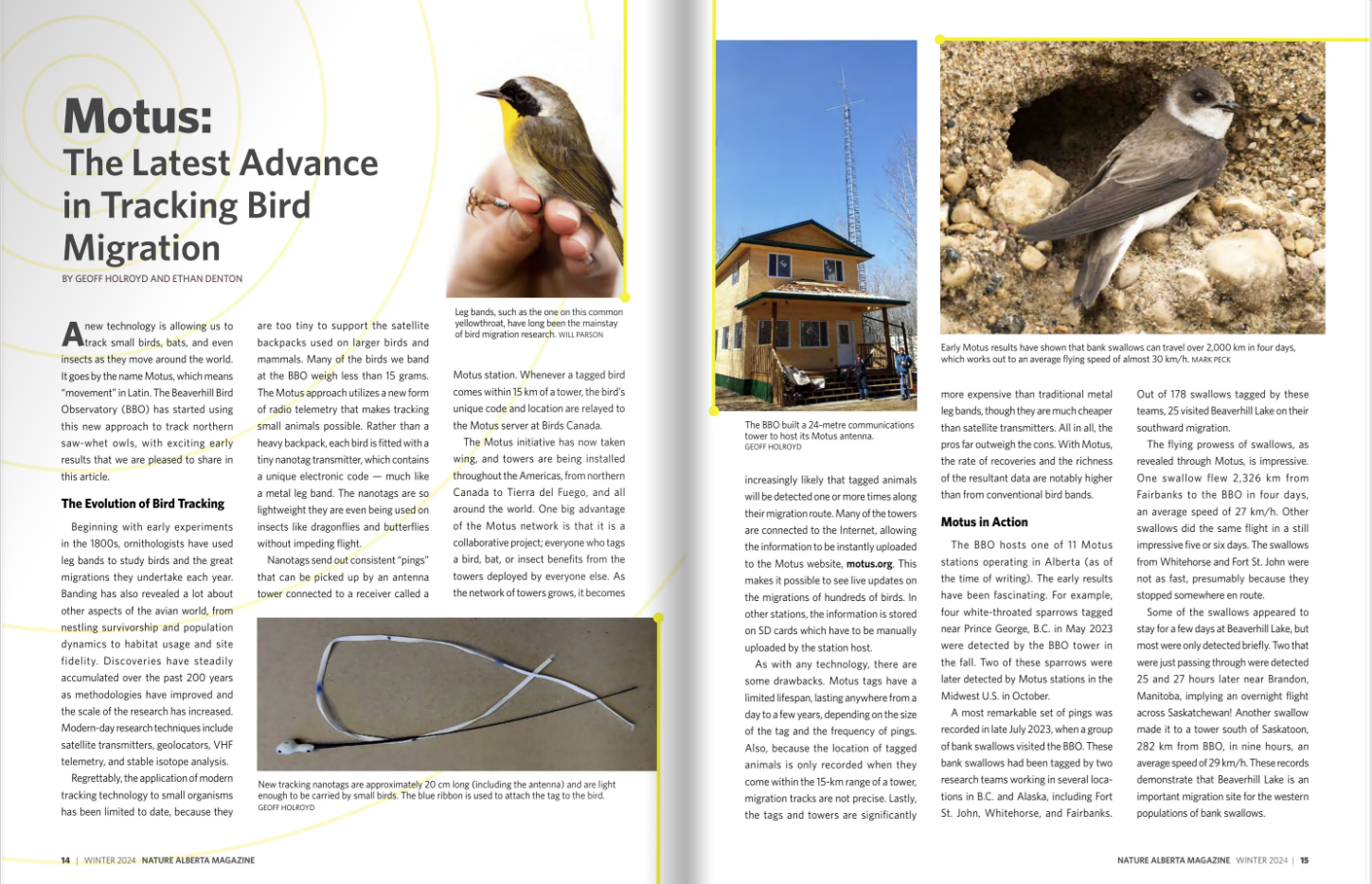

Beginning with early experiments in the 1800s, ornithologists have used leg bands to study birds and the great migrations they undertake each year. Banding has also revealed a lot about other aspects of the avian world, from nestling survivorship and population dynamics to habitat usage and site fidelity. Discoveries have steadily accumulated over the past 200 years as methodologies have improved and the scale of the research has increased. Modern-day research techniques include satellite transmitters, geolocators, VHF telemetry, and stable isotope analysis.

Regrettably, the application of modern tracking technology to small organisms has been limited to date, because they are too tiny to support the satellite backpacks used on larger birds and mammals. Many of the birds we band at the BBO weigh less than 15 grams. The Motus approach utilizes a new form of radio telemetry that makes tracking small animals possible. Rather than a heavy backpack, each bird is fitted with a tiny nanotag transmitter, which contains a unique electronic code — much like a metal leg band. The nanotags are so lightweight they are even being used on insects like dragonflies and butterflies without impeding flight.

Nanotags send out consistent “pings” that can be picked up by an antenna tower connected to a receiver called a Motus station. Whenever a tagged bird comes within 15 km of a tower, the bird’s unique code and location are relayed to the Motus server at Birds Canada.

The Motus initiative has now taken wing, and towers are being installed throughout the Americas, from northern Canada to Tierra del Fuego, and all around the world. One big advantage of the Motus network is that it is a collaborative project; everyone who tags a bird, bat, or insect benefits from the towers deployed by everyone else. As the network of towers grows, it becomes increasingly likely that tagged animals will be detected one or more times along their migration route. Many of the towers are connected to the Internet, allowing the information to be instantly uploaded to the Motus website, motus.org. This makes it possible to see live updates on the migrations of hundreds of birds. In other stations, the information is stored on SD cards which have to be manually uploaded by the station host.

As with any technology, there are some drawbacks. Motus tags have a limited lifespan, lasting anywhere from a day to a few years, depending on the size of the tag and the frequency of pings. Also, because the location of tagged animals is only recorded when they come within the 15-km range of a tower, migration tracks are not precise. Lastly, the tags and towers are significantly more expensive than traditional metal leg bands, though they are much cheaper than satellite transmitters. All in all, the pros far outweigh the cons. With Motus, the rate of recoveries and the richness of the resultant data are notably higher than from conventional bird bands.

Motus in Action

The BBO hosts one of 11 Motus stations operating in Alberta (as of the time of writing). The early results have been fascinating. For example, four white-throated sparrows tagged near Prince George, B.C. in May 2023 were detected by the BBO tower in the fall. Two of these sparrows were later detected by Motus stations in the Midwest U.S. in October.

A most remarkable set of pings was recorded in late July 2023, when a group of bank swallows visited the BBO. These bank swallows had been tagged by two research teams working in several locations in B.C. and Alaska, including Fort St. John, Whitehorse, and Fairbanks. Out of 178 swallows tagged by these teams, 25 visited Beaverhill Lake on their southward migration.

The flying prowess of swallows, as revealed through Motus, is impressive. One swallow flew 2,326 km from Fairbanks to the BBO in four days, an average speed of 27 km/h. Other swallows did the same flight in a still impressive five or six days. The swallows from Whitehorse and Fort St. John were not as fast, presumably because they stopped somewhere en route.

Some of the swallows appeared to stay for a few days at Beaverhill Lake, but most were only detected briefly. Two that were just passing through were detected 25 and 27 hours later near Brandon, Manitoba, implying an overnight flight across Saskatchewan! Another swallow made it to a tower south of Saskatoon, 282 km from BBO, in nine hours, an average speed of 29 km/h. These records demonstrate that Beaverhill Lake is an important migration site for the western populations of bank swallows.

Studying Saw-Whet Owls

In the fall of 2023, the BBO fitted 48 northern saw-whet owls with Motus nanotags. In this, we were breaking new ground because the techniques for attaching nanotags to small birds are still being developed. These tags cannot be attached like conventional leg bands; they have to be placed on the bird’s back using a miniature harness. Geoff Holroyd was able to develop a workable approach, drawing on his experience in building backpacks for satellite transmitters on larger birds. It took three weeks of trials with different materials to perfect the design, and by September 16 we were able to deploy the first tag. With some practice, we were able to reduce the attachment time to about ten minutes. At the World Owl Conference in Wisconsin in October, we confirmed that we had hit upon a novel attachment technique, improving on other designs.

We have already learned a lot. For example, we had always assumed that the migrating owls we caught in the fall were just passing through and would leave the Beaverhill Natural Area within a day or two. The nanotags tell a different story. Two tagged birds stayed within the 15-km range of BBO’s tower for over a month. Other owls remained for a week or so before heading further on their migration. During this time, the owls are completing their body moult. Saw-whet owls moult progressively over the summer, and in September most owls are still moulting body feathers. The occasional adult is still regrowing wing feathers. By October, the body moults are complete and the owls are ready for migration. Some have already migrated!

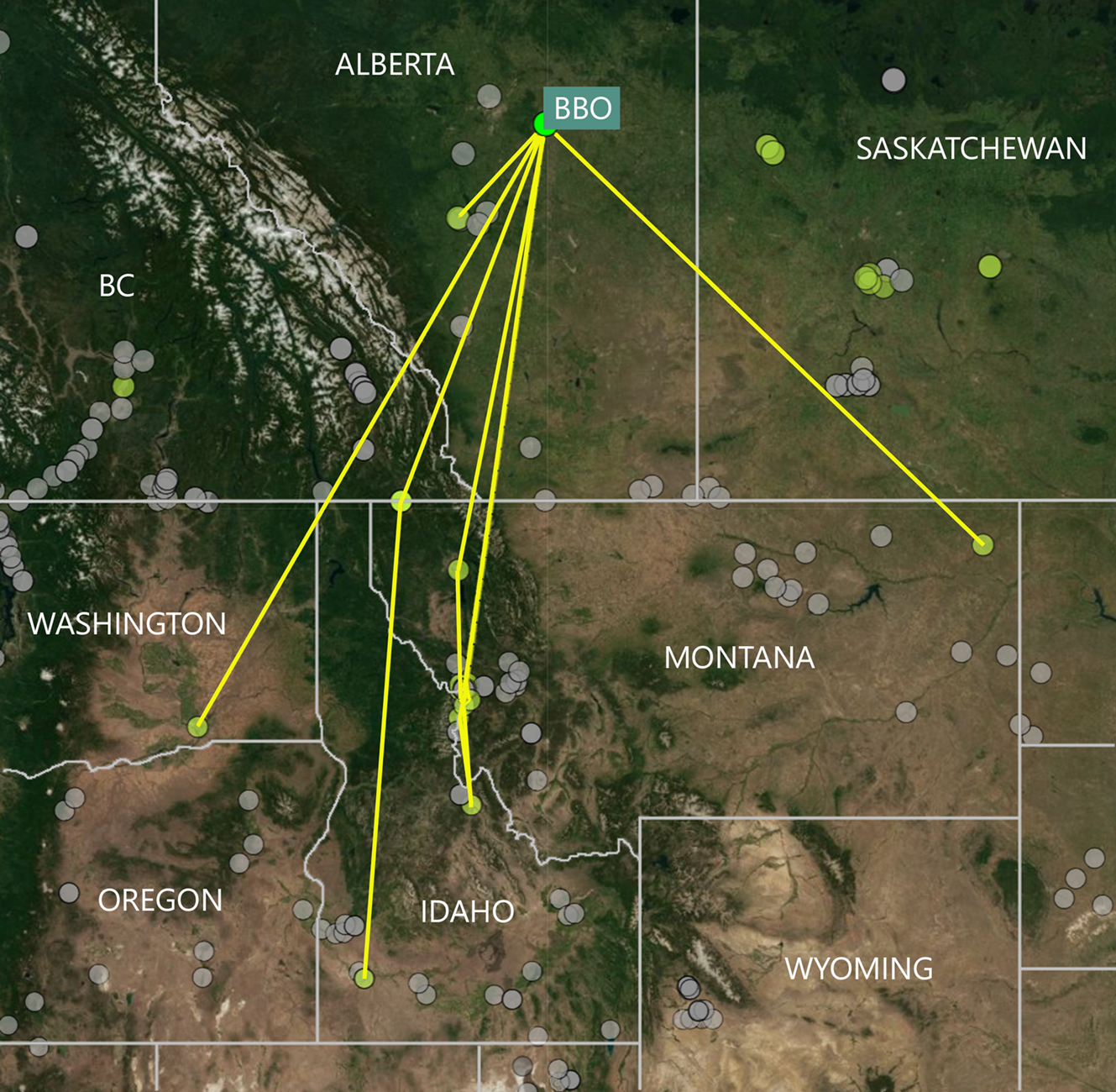

Additional surprises were in store after the tagged birds left our area. Earlier studies based on bird banding recoveries had suggested that most saw-whet owls from Alberta migrate to eastern Canada and then south into the U.S. However, most owl banding stations are located to the east, and very few banding stations are south and west of us. This may have skewed the results — it could be that we have been seeing an eastward migration because that is where we have been looking. The early Motus findings certainly paint a different picture, with the birds heading directly south (see accompanying map).

The migration tracks of saw-whet owls fitted with nanotags by the BBO in the fall of 2023. The birds travelled south into the western U.S.A. instead of flying eastward as expected on the basis of leg band studies.

Two of our tagged owls traveled southwest to Sylvan Lake. Another owl was detected on the shore of Koocanusa Lake, 500 km southwest of BBO on the B.C.-Montana border. This owl continued further south and was detected by a tower in southern Idaho a few days later. Four others birds were detected in Montana: one south of Waterton Lakes National Park, two south of Missoula, and the other in northeast Montana. The longest movement was an owl that flew to central Washington state. In summary, eight of our tagged owls were detected in the first month of the project and all eight flew south. None have flown east as predicted by bird band recoveries. This story will continue to develop, since the nanotags are designed to last for two years.

In the coming months, the new Motus tags will help us fill important information gaps about the spring movements of northern saw-whet owls in our region. Currently, all of our owl monitoring is done in the fall because the spring migration occurs when conditions are far too cold (and often snowy) to safely operate our banding station. With Motus, that’s all about to change. The towers will pick up tagged owls without us having to worry about the inclement conditions of March and April in Alberta.

Get Involved

Anyone interested in becoming involved with Motus in Alberta can start by sponsoring an owl’s tag at the BBO. The tags cost $300 each. Sponsors get to name their owl and receive updates on where and when the owl pings throughout the bird’s travels. The first 48 tags were all sponsored by individuals. Our tower was sponsored by the Edmonton Nature Club, Environment Canada, and by donations. Another great way to further this research is to install a Motus tower at your home, work, recreational property, or elsewhere. The hardware for a station costs about $5,000, not including a tower, power, and Wi-Fi. Anyone interested in supporting Motus research in Alberta is encouraged to visit the motus.org website or contact Geoff Holroyd at chair@beaverhillbirds.com.

Ongoing efforts to install a string of towers across southern Alberta will help ensure that as many birds as possible are detected when they enter the province (not only owls, but other species as well). Also, the more tags deployed the better, as every additional bird tagged vastly increases the odds of having a tagged bird pass by a tower. Whether it’s a local bird pinging off the same tower year after year, or a migrant registering a 3,000-km migration and ending up in an entirely different breeding ground, each and every data point collected by Motus helps create a mosaic of scientifically valuable maps. Already, tagged birds are bringing to light new areas of focus for crucial migration stopovers, threatened wintering grounds, and some of the many hazards posed by the birds’ biannual trek across the continent, and beyond.

We acknowledge the collaboration of the researchers who tagged the songbirds in this article, including Ken Otter (University of Northern B.C.), who tagged the white-throated sparrows, and Sarah Endenburg (Carleton University) and Julie Hagelin (Alaska Fish and Game), who tagged the bank swallows.

Geoff Holroyd is a retired research scientist with Environment and Climate Change Canada and adjunct professor at the University of Alberta. He is currently chair of the Beaverhill Bird Observatory. He published his first scientific article about saw-whet owls in 1975.

Ethan Denton is one of the top young birders in Alberta and currently in first year at Lethbridge College. In 2023 he was an assistant biologist at Beaverhill Bird Observatory.

Read the Original Article for this Post

For a richer reading experience, view this article in the professionally designed online magazine with all images and graphs in place.

This article originally ran in the Winter 2024 issue of Nature Alberta Magazine (Vol. 53 | No. 4).