Peregrine Recovery: Management in the New Millennium

18 October 2024

BY GORDON COURT

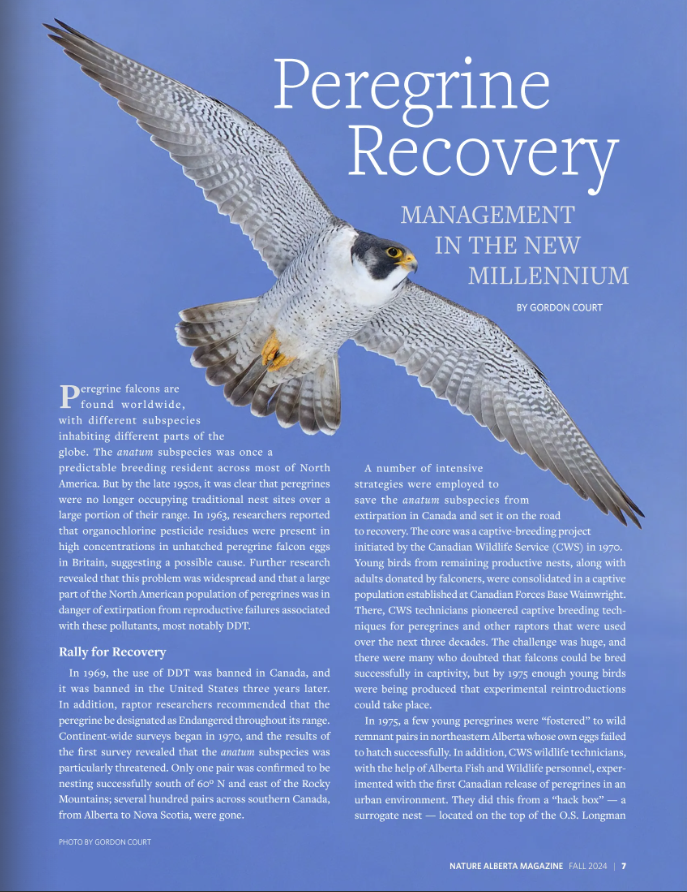

Peregrine falcons are found worldwide, with different subspecies inhabiting different parts of the globe. The anatum subspecies was once a predictable breeding resident across most of North America. But by the late 1950s, it was clear that peregrines were no longer occupying traditional nest sites over a large portion of their range. In 1963, researchers reported that organochlorine pesticide residues were present in high concentrations in unhatched peregrine falcon eggs in Britain, suggesting a possible cause. Further research revealed that this problem was widespread and that a large part of the North American population of peregrines was in danger of extirpation from reproductive failures associated with these pollutants, most notably DDT.

Rally for Recovery

In 1969, the use of DDT was banned in Canada, and it was banned in the United States three years later. In addition, raptor researchers recommended that the peregrine be designated as Endangered throughout its range. Continent-wide surveys began in 1970, and the results of the first survey revealed that the anatum subspecies was particularly threatened. Only one pair was confirmed to be nesting successfully south of 60º N and east of the Rocky Mountains; several hundred pairs across southern Canada, from Alberta to Nova Scotia, were gone.

A number of intensive strategies were employed to save the anatum subspecies from extirpation in Canada and set it on the road to recovery. The core was a captive-breeding project initiated by the Canadian Wildlife Service (CWS) in 1970. Young birds from remaining productive nests, along with adults donated by falconers, were consolidated in a captive population established at Canadian Forces Base Wainwright. There, CWS technicians pioneered captive breeding techniques for peregrines and other raptors that were used over the next three decades. The challenge was huge, and there were many who doubted that falcons could be bred successfully in captivity, but by 1975 enough young birds were being produced that experimental reintroductions could take place.

Custom-designed by Steve Schwartze, this hack box, complete with a “baby gate” that prevents peregrines from jumping from the box at too young an age, helps ensure high levels of fledging success. STEVE SCHWARTZE

In 1975, a few young peregrines were “fostered” to wild remnant pairs in northeastern Alberta whose own eggs failed to hatch successfully. In addition, CWS wildlife technicians, with the help of Alberta Fish and Wildlife personnel, experimented with the first Canadian release of peregrines in an urban environment. They did this from a “hack box” — a surrogate nest — located on the top of the O.S. Longman Building in Edmonton, beginning in July of 1976. One of the four birds released that first summer — a male — was observed later that year in Belize, Central America, demonstrating the effectiveness of hacking as a reintroduction technique. Another Alberta peregrine success occurred in 1977, when one of the foster birds from 1975 was discovered breeding at a nest site near Fort Chipewyan. This bird was the first captive-raised peregrine falcon in the world to return and breed in the wild — a tremendous “feather in the cap” of the Canadian peregrine recovery effort.

In the late 1970s, hack releases of peregrines occurred at various locations in Alberta, in both urban and rural areas. Alberta Fish and Wildlife biologists working in the O.S. Longman Building were well situated to keep track of returning birds, and they recorded several adult birds visiting the building by 1979. The ultimate success came in 1980, when a nesting site of a pair of peregrines was discovered on the Alberta Government Telephones (now Telus) building in Edmonton. This pair became the first captive-produced peregrines to pair and breed in Canada. Fostering young to wild pairs continued to occur in northeastern Alberta, and with the combined efforts of the Alberta Fish and Wildlife Division, CWS, and Wood Buffalo National Park staff, this northern population began to show signs of slow recovery.

Back from the Brink

The early 1990s brought a renewed vigour to the Alberta peregrine reintroduction program. Buoyed by declining DDT residues in prey, and novel corporate sponsorship, a large-scale release program was initiated in 1992. The CWS Wainwright facility continued to operate, largely on a cost-recovery basis, and provided all the young for the stepped-up Alberta releases. Mass hack releases were undertaken on the Red Deer River and, during the next decade, the central Alberta population would grow from two to over 20 pairs, several of them returning to breed on man-made structures. Dozens of budding biologists took part in this extensive release program and many of them now hold positions in various conservation agencies across Canada.

The CWS breeding facility closed in 1995, after having produced more than 1,500 peregrines over 25 years, with birds released across southern Canada. It was decided that there were now enough wild peregrines to assure sufficient reproduction in the wild. Moreover, analysis of pesticide residues in peregrine eggs showed that eggshell thinning was no longer limiting to the population. The population had finally started a strong rebound after over 20 years of concentrated recovery efforts.

The ultimate sign of success: An adult peregrine leaves the eyrie shortly after feeding her young at a nest site unoccupied by peregrine falcons since 1956. JON GROVES

Bans on the use of DDT in Canada and the United States and close to three decades of intensive management by federal and provincial bodies led to recovery of the anatum peregrine falcon over most of its historical range by the early 2000s, with several hundred pairs reoccupying historically used nest sites throughout southern Canada. The falcon was downlisted to Threatened by the Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada in 2007 and was later delisted to Not at Risk by the same committee in 2017.

Peregrines in Alberta

Ironically, despite playing such a large part in the countrywide recovery of the anatum peregrine, Alberta was among the last jurisdictions to show a complete recovery of the population. The recovery of populations in northeastern Alberta and Wood Buffalo Park was spectacular; however, historically used nest sites along southern rivers, including the upper North Saskatchewan, Red Deer, Pembina, and Bow, were largely unoccupied even by 2010.

To achieve the recovery goal of having at least 70 breeding pairs distributed across the peregrine’s entire historical range in Alberta, and again having access to corporate donations, a new hack release program was initiated in 2011. Alberta Environment and Protected Areas led the initiative, with support from several other organizations and the cooperation of landowners Mary-Anne and Larry Law. This time, the captive-raised young were released near a historically occupied nest site on the Pembina River bordering the Pembina River Provincial Park — a cliff last used in 1964. Young birds collected at urban and industrial nest locations throughout the province, where post-fledging mortality was known to be chronically high, were also added to the releases.

Steve Schwartze adds a young peregrine, fresh from being picked up from between the traffic lanes of 170 Street in Edmonton, to a hack box. GORDON COURT

The project met with almost immediate success. An adult peregrine pair began breeding at the site in 2014, 50 years to the month since the Pembina River last hosted a pair of peregrines. This success was widely celebrated, but it did have one downside. The nesting pair had chosen to occupy the site that managers had been using for reintroductions, potentially making it unusable. Master falconer and falcon breeder Steve Schwartze, who conducted all the Pembina releases, said, “Not so fast.” Knowing that adult peregrine pairs in dense populations often tolerated the presence of juvenile peregrines from other nests within their territories while their own young were in the fledgling stage, Schwartze was keen to continue the hack. He felt that “as long as the young from the wild pair fledge first and we supplement with plenty of extra food, there is a good chance they will treat any released birds as their own. It all comes down to the personalities of the adults.” Fortunately, he was right!

Captive stock and rescued fledglings continued to be released at the Pembina site during the entire lifespan of the breeding pair that was established in 2014. A total of 228 birds fledged at this beautiful location over the last 13 seasons (see Figure 1), including several young produced by the territorial pair. These juveniles matured and went on to occupy nest sites in central Alberta that have been abandoned by peregrines since the late 1950s and 1960s, while others came back to nest in urban and industrial settings. Some of the Pembina birds have also been photographed over the years while on migration through locales as near as the Inglewood Bird Sanctuary in Calgary and as far away as Texas.

Plans are in place to continue to release rescued peregrine young from the Pembina location, as the most significant predators of young peregrines — golden eagles and great horned owls — appear to be absent from the area, and fledging success is very high. Time has passed, and the original pair of tolerant foster parents are now gone. We will cautiously test the patience of the new pair in hopes of continuing this successful and inexpensive way of managing the species to complete recovery. With continued success, it is very likely we can remove the peregrine falcon from Alberta’s list of species at risk within the next decade! This magnificent species has made its return to its historic range our province — back by popular demand!

Gordon Court has worked on the recovery of the peregrine falcon in western Canada for over four decades and is recognized internationally as an expert on this species. He is the former Canadian Director of the U.S.-based Raptor Research Foundation. Presently, he is the Provincial Wildlife Status Biologist for Alberta Environment and Protected Areas.

Read the Original Article for this Post

For a richer reading experience, view this article in the professionally designed online magazine with all images and graphs in place.

This article originally ran in the Fall 2024 issue of Nature Alberta Magazine (Vol. 54 | No. 3).