The State of Alberta’s Birds

16 April 2025

By NICK CARTER

In October of 2024, Birds Canada released their State of Canada’s Birds report, which tracked changes in the populations of different species categories based on shared lifestyles — such as birds of prey, grassland birds, aerial insectivores, etc. — from 1970 to 2024.1 While some population trends showed stability or even notable increases, the report shows that most of Canada’s bird populations are in decline. This data has mixed implications for Alberta and the birds that live here; some promising, and some concerning.

To get a more Alberta-centric view of changes in bird populations over time, we can use the report’s population trends in the species Distribution and Occurrence maps and explore public data on different species in the Status and Trends page on eBird.2 The latter resource provides trends in a narrower timeframe, generally from 2012–2022, and doesn’t include data on certain species during the time of year they are found in Alberta; however, we can see recent trends in many bird populations across different parts of the province.

First, the good news. Nationwide, waterfowl populations have increased by 46%, and all native goose and swan populations are increasing in Canada. Birds Canada found that freshwater ducks on average have increased by 38%, and that most species are either stable or increasing. What breeding season data there is on eBird does show good increases in things like gadwalls and cinnamon teals in the province, but Birds Canada found declines in species such as the American wigeon and white-winged scoter. Dry conditions in the prairies could be making this worse, according to Birds Canada.

The next biggest increase in Canada, at 35%, has been the birds of prey category. From 2012–2022, eBird shows that turkey vultures increased by 36.2% and seem to be expanding their range northwards. Since 1970, the osprey has seen a nationwide increase, perhaps in part because of artificial nest platforms; however, data from 2012–2022 shows a slight decline of this species in Alberta. Our population of golden eagles remains stable, and bald eagles have increased by 16.5% over the past 10 years.

Northern harriers are decreasing both in Alberta and nationwide, likely because of grassland and wetland habitat loss, as well as pesticides in their prey. The accipitrine hawks have been reported as stable since 1970 in Canada, but eBird data from Alberta shows recent declines of all three species, with a worrying 37.2% decline in the sharp-shinned hawk. The soaring Buteo hawks show either stability or population increases. Some owls, such as the barred owl, show increases both nationwide and in Alberta; others, such as the snowy, short-eared, and burrowing owls, are in decline. Some owls are either data deficient, like the boreal owl, or show nationwide increases overall since 1970, but with recent local declines, including the northern saw-whet and northern hawk owls. In falcons, merlin populations are increasing, and peregrines have improved since their threatened days in 1970, but do show a recent decline on eBird of 21.8% in Alberta. Prairie falcons are relatively stable here, but American kestrels and gyrfalcons continue to decline.

For certain owls of more remote areas, such as the boreal owl, we need more data to get a better understanding of how their populations are doing. NICK CARTER

In the category of wetland birds, including a variety of disparate groups, some already discussed, there has been a 21% increase nationwide since 1970. Many wetland songbirds are either stable or increasing. Grebes have largely remained stable since 1970, though the western grebe remains sensitive and both it and the pied-billed grebe show declines in Alberta. The Virginia rail has increased here by 30.8%. American coots, on the other hand, have decreased by a startling 37.4% after a record high in the 2010s. This may be because of dry conditions in the prairie wetlands.

All of Alberta’s tern species have declined. Aside from the ring-billed gull, our gull species are in decline. White-faced ibises, once only known in the far south of Alberta, are on the rise and expanding their range northwards. Double-crested cormorants and American white pelicans have increased, and great blue herons have remained stable. However, the American bittern and black-crowned night heron have decreased alarmingly, by 43.5% and 44.8% respectively, in the past decade.

Following an increase in the ’80s and ’90s, forest birds have essentially returned to 1970 levels. Spruce grouse in Alberta have slightly declined in the north and parts of the foothills, but they are increasing in the protected mountain parks. Our woodpeckers are in good shape, aside from the American three-toed, which is decreasing in Canada. Most flycatchers are decreasing in Alberta, especially the olive-sided flycatcher and western wood-pewee. While the boreal chickadee has declined by 17.1% in the past decade, our other chickadees, vireos, jays, and kinglets are secure, and both nuthatches have increased. The hermit thrush is in decline and has decreased in Alberta by a concerning 40.5% over the last decade. The bohemian waxwing has also decreased by a similar degree. Alberta’s urban areas show the worst level of population decrease, which is puzzling given the modern abundance of ornamental trees in towns and cities that provide winter fruit for this species. The evening grosbeak has been doing poorly in eastern and Pacific Canada but remains relatively stable, if uncommon, in Alberta. Along with many other finches, the evening grosbeak tends to have erratic distributions from one year to the next; but, overall, most of our finches are in decline. The warblers are stable, though the populations of some species fluctuate. Some, like the blackpoll, have been hit hard both nationally and in Alberta.

Canada’s arctic birds have decreased by 28% since 1970. Long-distance migrant species have a lot of overlap with this category and have declined by nearly the same amount at 29%. Many arctic-nesting and/or long-distance migrants that move through Alberta are shorebirds, which in turn have decreased nationally by 42%. It’s not exclusively bad news for shorebirds. In recent decades, the black-necked stilt, once a southeastern Alberta rarity, has established itself in the prairies and parkland and continues to increase in Alberta. Their close relative, the American avocet, is also becoming more common in central Alberta. Among upland sandpipers, the prairie population is on the rise, except in the northwest, where it’s in decline. For the rest of our shorebirds, it’s a mostly bleak affair. Plovers, godwits, dowitchers, and most Calidris sandpipers have moderately to substantially declined. Meanwhile, the shanks and tattlers are showing mixed results. In Alberta, the willet has remained stable, and both the solitary sandpiper and greater yellowlegs have modestly increased, but the lesser yellowlegs has declined. The reasons for the state of shorebird and arctic breeders are complicated, but loss of habitat on their migration routes is a contributing factor.

Marbled Godwit: Marbled godwits, one of our largest shorebirds, have experienced a substantial population decrease in the Alberta grasslands. TONY LEPRIEUR

Aerial insectivores have decreased in Alberta to a similar degree as the shorebirds. Already uncommon in Alberta, both the black and Vaux’s swift are declining. The eastern phoebe has decreased by 15.7% since 2012, but the group in the most trouble might be swallows. Aside from the recent increase of purple martin, the rest of Alberta’s swallows are in decline. Many of these species hunt for insects in and around wetlands, and as these environments dry out, fewer insects are reproducing, leaving swallows with less to eat. As well, recent high summer temperatures have led to widespread nest failures in cavity-nesting songbirds, such as tree swallows and mountain bluebirds.

By far the hardest-hit group in Canada is the grassland birds, which have declined by 67% since 1970. This not only includes prairie grouse, such as the greater sage-grouse, and birds of prey, such as the burrowing owl, but a variety of grassland songbirds. The chestnut-collared and thick-billed longspurs, prairie sparrows (such as the grasshopper, Brewer’s, and vesper sparrows), and western meadowlark are all in decline. In most of our grassland sparrows, the decline has been roughly 25% since 2012, but in that time the lark bunting has dropped by a staggering 61.1% in Alberta. The crisis these grassland birds are experiencing is mostly because of habitat loss. Most of Alberta’s grasslands have been cultivated for agriculture, replacing native plant species with crops.

We know what the birds of Alberta are dealing with, and while some problems are multifaceted or hard to understand, there are a few clear takeaways. Firstly, past conservation efforts to save once-endangered species have worked, so there’s still hope. Secondly, the drying of Alberta’s lakes and wetlands and the broader effects of climate change are negatively affecting a variety of species, from sandpipers to swallows. Lastly, Alberta’s native grasslands are a threatened ecosystem; if we lose the grasslands, we will also lose the grassland birds.

We must get more of our native grasslands under protection. Currently less than 2% of this region lies within protected areas. Agricultural methods that are less harmful to wildlife and environments like grasslands and wetlands would also help matters. Albertans can help birds in a variety of ways, such as planting native trees and shrubs instead of grassy lawns; supporting causes, organizations, and politicians that promote ecologically friendly policies; and contributing to citizen science projects (for example, reporting bird sightings on sites like eBird and iNaturalist to help biologists gather more data). Captive breeding, banning pesticides, and eliminating hunting are conservation efforts that have helped save species that were once almost lost, such as the trumpeter swan and peregrine falcon. To a whole generation, these species were icons of avian conservation in North America. Perhaps it’s time we focus on some new ones to represent what might be lost tomorrow if we don’t act today.

References:

- Birds Canada and Environment and Climate Change Canada (2024). The State of Canada’s Birds Report. https://naturecounts.ca/nc/socb-epoc/report/2024/en/

- eBird Status and Trends. https://science.ebird.org/en/status-and-trends

Nick Carter is a naturalist and science communicator from Edmonton and is Nature Alberta’s Nature Kids Coordinator. He studied biology at the University of Alberta and has had a lifelong fascination for all things in the natural world.

Read the Original Article for this Post

For a richer reading experience, view this article in the professionally designed online magazine with all images and graphs in place.

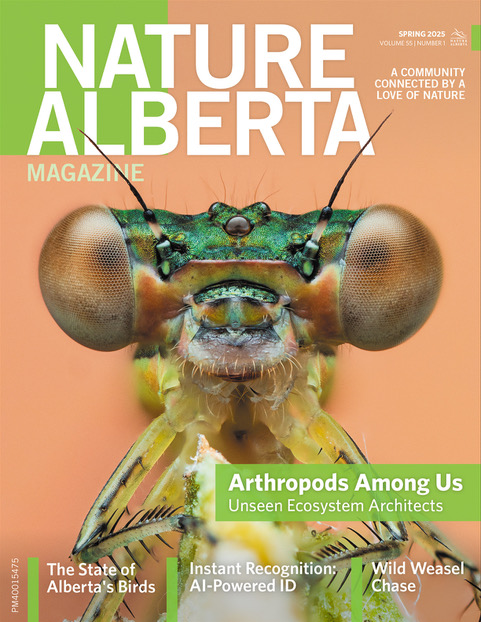

This article originally ran in the Spring 2025 issue of Nature Alberta Magazine (Vol. 55 | No. 1).