A Fisheye View of Cumulative Effects in Alberta’s Southern East Slopes

BY SARAH MILLIGAN

In photography, a fisheye lens allows the photographer to capture an extremely wide angle of view. You can take a snapshot of an entire landscape complete with mountains, forests, meadows, and lakes. If you are a photographer exploring Alberta’s southern East Slopes, your fisheye lens might capture just that—a seemingly untouched, beautiful landscape. Turn around and point your lens in another direction, however, and you might see a road crisscrossing a cold mountain stream and well sites, cutblocks, and random campsites dotting the background. This is actually a very busy landscape.

The southern East Slopes region is both busy and ecologically significant. It is home to the headwaters of the Bow and Oldman Rivers and provides a number of ecological services, including fresh water for downstream communities and irrigation districts, habitat for numerous native species, and world-renowned tourism and recreation activities. Its natural resources support forestry, oil and gas, mining, ranching, and agriculture.

However, no landscape can provide an inexhaustible supply of benefits to humans. And in the southern East Slopes region, there are growing indications that a tipping point has been reached. Wildlife — particularly our native fish species — are illustrative of this. Native fish communities are acutely sensitive to landscape and watershed mismanagement, which makes them an important indicator species. If they’re not doing well, it’s a signal that other aquatic and terrestrial wildlife might not be doing too well either.

Bull trout, the only native char to historically occupy all the drainages of Alberta’s Eastern Slopes, and westslope cutthroat trout, the only subspecies of cutthroat trout native to Alberta, inhabit the cold waters found along Alberta’s East Slopes. Both are listed as threatened species in Alberta and have exper-ienced rapid declines in abundance and distribution due to progressive habitat alteration and changes in climate. Westslope cutthroat trout once inhabited most streams in southwestern Alberta from the alpine zone to the prairies, but today are largely restricted to the Rocky Mountains and foothills.1 Bull trout have also experienced a significant westward contraction of their historic range.2

As Lorne Fitch, professional biologist and former adjunct professor with the University of Calgary, puts it: “Native trout declines are a message hard to ignore. Their plight is a signal that many of the values Albertans hold for the East Slopes are at risk.”3 Given the alarms these species are sounding, it’s time to ask serious questions about the future of this important region. What will the landscape and wildlife populations look like? What is our land-use trajectory and is it sustainable? If it’s not, how do we change our trajectory?

To answer these questions, we need to put down our camera and pick up another tool called ALCES: A Land Cumulative Effects Simulator. ALCES is a computer model that tracks land-use activities and their accumulating footprint over time at high resolution. It allows us to understand how landscapes will change over time and to assess the ecological effects of these changes. The model does this by integrating scientific findings obtained through ecological field studies and then applying these findings to future landscapes.

For example, studies have shown that industrial processes — including timber harvest, mining, oil and gas exploration and extraction, and the associated access roads — cause habitat fragmentation, which negatively affects trout populations. Industrial access roads also facilitate entry to remote areas by anglers, which increases angling pressure. Roads and other industrial features can also lead to greater frequency and intensity of flooding, blockages and changes in water flows, and increased sediment and phosphorus loads.

Assessments of future landscapes also need to take climate warming into account. Bull trout and westslope cutthroat trout are at particular risk because they are cool-water species and become stressed by warmer water temperatures. Progressive changes in climate will also have a dramatic effect on the water cycles, which in turn will impact stream flows, water quality, spawning substrates, food availability, and disease risk for aquatic species.4

By integrating all of this ecological information and applying it to evolving future landscapes, ALCES can predict how trout and other species are likely to fare in coming decades. We can use the model to explore alternative management scenarios, helping us to understand the implications of today’s actions on tomorrow’s landscapes. Such studies afford us a glimpse into alternative futures and allow us to select the future we want.

In 2019, the Alberta Chapter of The Wildlife Society (ACTWS) commissioned a cumulative effects assessment of this type for Alberta’s southern East Slopes. The overarching goal was to provide a science-based assessment of two alternative management scenarios and to use that to inform land use and conservation planning in the region. One scenario, the business-as-usual model, assumed that resource development would continue along its current trajectory. A second scenario, the protection model, placed an emphasis on protecting the land from further industrial development. The protection scenario also assumed that non-permanent industrial footprints (access roads, seismic lines, and well sites) would be reclaimed and that a combination of access management and regulatory protection would lower angling mortality to levels observed in other protected areas in the province.

Several outcome measures were used to assess the consequences of each scenario, taking cumulative effects fully into account. The focus was on bull trout and westslope cutthroat trout viability, measured in terms of the Alberta government’s Fish Sustainability Index.5 Additional environmental metrics included the overall intensity of the industrial footprint, the amount of intact land, water quality, and an indicator of approximate water flow. Natural resource gross domestic product was used to assess economic outcomes.

The analysis afforded a fisheye view of the future of Alberta’s southern East Slopes — and it doesn’t look good under the business-as-usual model. The Fish Sustainability Index is predicted to progressively decline as human and climate-induced stressors progressively degrade freshwater habitats. Consequently, further declines in the abundance and distribution of bull trout and westslope cutthroat trout can be expected. Few sustainable populations are likely to remain outside of protected areas.

Fortunately, there is an alternative. If we train our fisheye lens on a future landscape that is protected rather than developed, things look much better for trout. Watershed protection resulted in substantial risk reduction in several watersheds, allowing fish sustainability to stay at moderate risk 50 years into the future despite climate change. Factors contributing to the effectiveness of protecting these watersheds include higher elevation and therefore lower sensitivity to climate warming, relative habitat intactness, and the potential for habitat reclamation. The potential to reduce access is also critical for lowering angling pressure, which was identified as a limiting factor for both trout species.

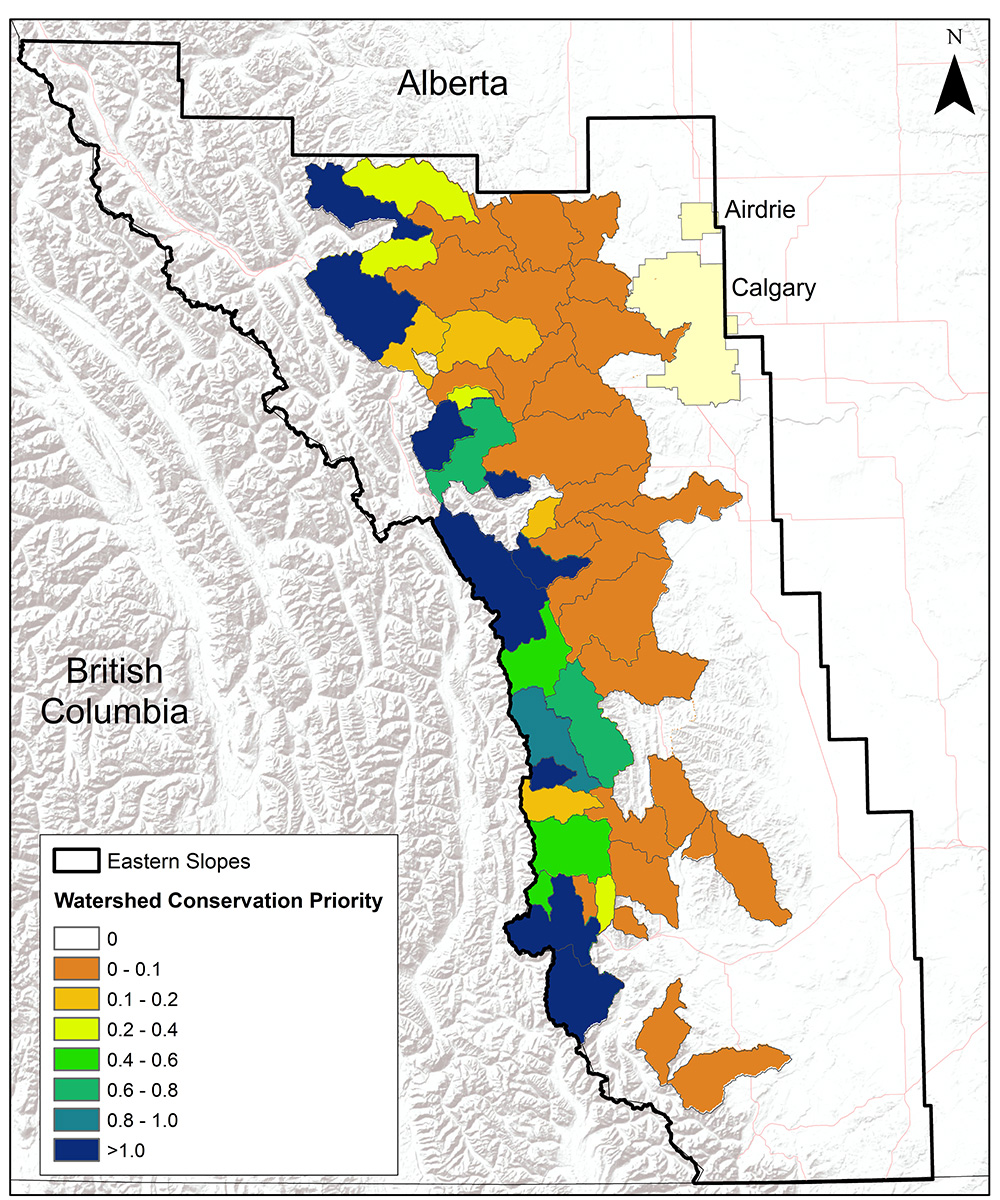

By comparing the Fish Sustainability Index and natural resource GDP results under the two management scenarios, it was possible to identify the watersheds where environmental benefits were greatest and the economic costs of protection were lowest. Most of these priority areas for conservation were in western watersheds (Figure 1). Fortunately, these watersheds have low potential for new oil and gas development. Therefore, the economic consequences of protection relate mainly to forest harvesting, which contributes much less to GDP than energy development. The upshot is that western watersheds are both of highest value to trout and carry the lowest cost of protection. For an area described as the last stronghold for trout populations in the region, this is good news.

The cumulative effects assessment found that other environmental outcome measures displayed a similar spatial pattern to trout sustainability, indicating that land-use impacts encompass the broader ecosystem. Water quality and intact land cover are low in the eastern downstream portion of the study area, where land conversion to agriculture and settlement is widespread. In the business-as-usual scenario, resource development caused further habitat fragmentation of the landscape, with intact land cover being largely limited to protected areas after five decades. In addition to the ecological implications, this can also lead to hydrologic changes, including elevated risk of runoff and downstream flooding.

The view from our model-assisted fisheye lens is quite clear. This isn’t just a fish issue, it’s an entire ecosystem issue. Achieving a balance in the southern East Slopes — ecologically, economically, and socially — will require more than maintaining the status quo. Conservation action will be needed to maintain viable native fish communities along with other natural capital values. Furthermore, we know where this action should be targeted. The cumulative effects assessment has identified target areas where there are good prospects for protecting or restoring values and the where costs of protection can be minimized.

So, now that you’ve seen a glimpse into the world of tomorrow, how does it feel to be there? Are you happy with the status quo or would you rather see a different trajectory for Alberta’s Southern East Slopes?

There is opportunity for change. As surprising as it may sound, watershed planning for the East Slopes of Alberta is still in its infancy. Management decisions regarding our resources occur at many levels, from individual landowners through to government-led regional planning. As fisheries biologist Jennifer Earle describes: “As an individual, you might not think there is much you can do to address large landscape threats such as sedimentation, man-made barriers to fish passage, and climate change. As part of a group, however, you can get involved in stewardship initiatives that help champion these issues and effect change at a local scale through volunteer projects.”6 The Alberta Chapter of The Wildlife Society and organizations like it need members and financial support to continue to engage in science-based conservation and management of wild animals and wild spaces. Please consider lending a hand.

Coal Mining in the Southern East Slopes

The Alberta Chapter of The Wildlife Society, along with other groups like the Canadian Parks and Wilderness Society, the Crowsnest Conservation Society, Timberwolf Wilderness Society, and Livingstone Landowners Group, recently participated in the Grassy Mountain Mine Public Hearing. Benga Mining Ltd. is proposing to construct and operate an open-pit metallurgical coal mine near the Crowsnest Pass, approximately seven kilometres north of the community of Blairmore. As proposed, the life of the mine is about 25 years. The hearing was an opportunity for groups and individuals to voice their support or opposition to the proposed coal mine. It was also an ideal platform for presenting the results of the cumulative effects assessment, which included the proposed Grassy Mountain coal mine footprint and its estimated revenue in the analysis. The results indicate that the watershed containing the proposed coal mine is ranked as a high-priority watershed, suggesting that the conservation benefits to trout and ecosystem services over the long-term outweigh the short-term economic gains from the mine.

Without the clarity of a fisheye view into the future of Alberta’s southern East Slopes, that message is eyebrow-raising. It’s an important reminder that the people who reside, work, or play in these watersheds, as well as those who never set foot in the watershed but still value it, need the tools of this report to inform decisions about the future. The Grassy Mountain Mine is unlikely to be the last large-scale development project to be proposed for Alberta’s southern East Slopes. In 2020, the government of Alberta rescinded the 1976 Alberta Coal Policy, which has opened headwaters in the East Slopes to open-pit coal mining. This is additive, of course, to the myriad of other land-use pressures that have already put the health and function of an ecologically significant landscape at risk.

References:

1. Alberta Westslope Cutthroat Trout Recovery Team. 2013. Alberta Westslope Cutthroat Trout Recovery Plan: 2012-2017. Alberta Environment and Sustainable Resource Development, Alberta Species at Risk Recovery Plan No. 28. Edmonton, AB, 77 pp. Accessed from open.alberta.ca/publications/9781460102312

2. Alberta Sustainable Resource Development. 2012. Bull Trout Conservation Management Plan 2012-17. Alberta Sustainable Resource Development, Species at Risk Conservation Management Plan No. 8. Edmonton, AB, 90 pp. open.alberta.ca/publications/9781460102305

3. Fitch, Lorne (2020). “A Dangerous Man with a Dangerous Concept.” Nature Alberta Magazine, 50(3), 12-14.

4. Ebersole, J.L., R.M. Quiñones, S. Clements and B.H. Letcher (2020). Managing climate refugia for freshwater fishes under an expanding human footprint. Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment, 18(5), 271-280.

5. Fish Sustainability Index was estimated according to Alberta Environment and Parks’ Cumulative Effects Joe Model, which was developed to assess multiple threats to aquatic species at risk in Alberta.

6. Earle, Jennifer (2020). “Alberta’s Bull Trout Need Our Respect – and Our Help.” Nature Alberta Magazine, 50(2), 8-11.

Sarah Milligan is a Professional Biologist whose interests include wildlife, habitat, and landscape ecology. She lives and works in Alberta and holds a M.Sc. in Conservation Biology and Environmental Science from the University of Alberta.

This article originally ran in Nature Alberta Magazine - Winter 2021