The Black Bear

22 April 2024

BY NICK CARTER

The American black bear represents different things to people. Visitors to the Rockies all hope to spot a bear, unless that means encountering it on the trail or finding it breaking into the camp cooler. The black bear is also an important figure in the spirituality of Indigenous peoples. But aside from the mix of love and fear we have for this species, the black bear is a fixture of the Alberta wilderness, and worthy of our understanding and respect.

The black bear is the smallest of North America’s three bear species (black, grizzly, and polar bears). In Alberta, adult males get up to about 170 kg and 1.5 metres long. Females are about two-thirds that size. American black bears are widespread across North America, from Alaska to northern Mexico. Its closest living relative is the Asiatic black bear, which is found throughout central and southern Asia.

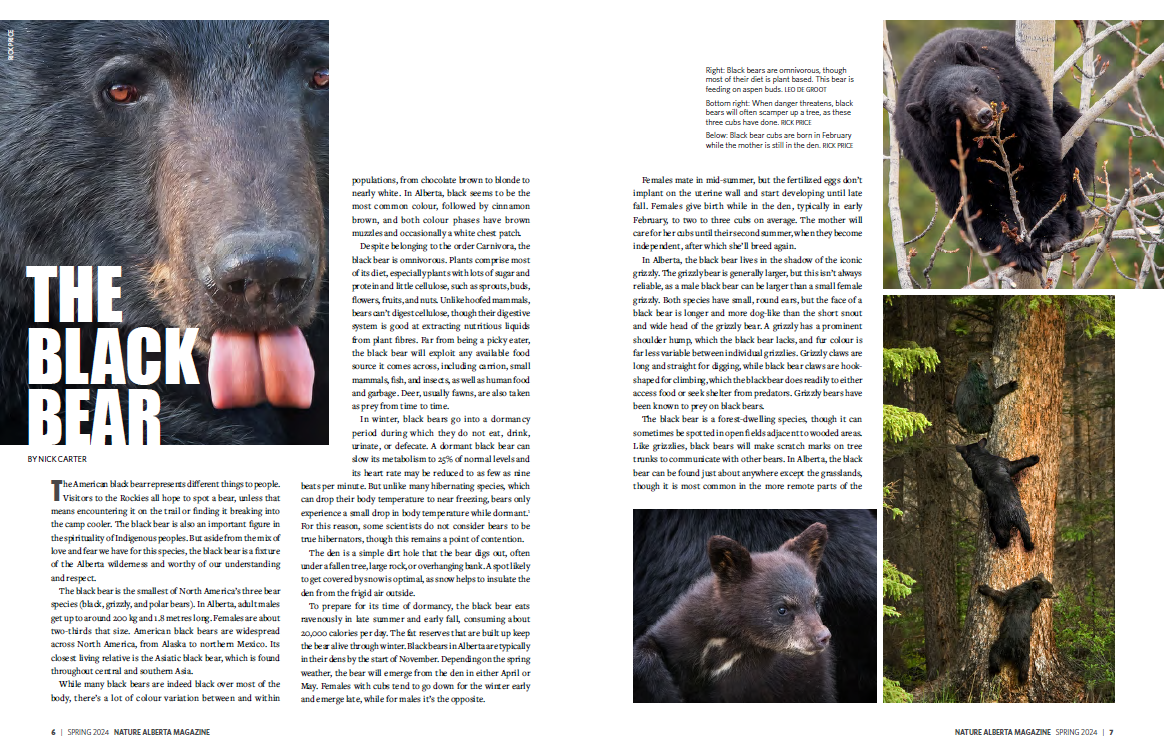

While many black bears are indeed black over most of the body, there’s a lot of colour variation between and within populations, from chocolate brown to blonde to nearly white. In Alberta, black seems to be the most common colour, followed by cinnamon brown, and both colour phases have brown muzzles and occasionally a white chest patch.

Despite belonging to the order Carnivora, the black bear is omnivorous. Plants comprise most of its diet, especially plants with lots of sugar and protein and little cellulose, such as sprouts, buds, flowers, fruits, and nuts. Unlike hoofed mammals, bears can’t digest cellulose, though their digestive system is good at extracting nutritious liquids from plant fibres. Far from being a picky eater, the black bear will exploit any available food source it comes across, including carrion, small mammals, fish, and insects, as well as human food and garbage. Deer, usually fawns, are also taken as prey from time to time.

In winter, black bears go into a dormancy period during which they do not eat, drink, urinate, or defecate. A dormant black bear can slow its metabolism to 25% of normal levels and its heart rate may be reduced to as few as nine beats per minute. But unlike many hibernating species, which can drop their body temperature to near freezing, bears only experience a small drop in body temperature while dormant.1 For this reason, some scientists do not consider bears to be true hibernators, though this remains a point of contention.

The den is a simple dirt hole that the bear digs out, often under a fallen tree, large rock, or overhanging bank. A spot likely to get covered by snow is optimal, as snow helps to insulate the den from the frigid air outside.

To prepare for its time of dormancy, the black bear eats ravenously in late summer and early fall, consuming about 20,000 calories per day. The fat reserves that are built up keep the bear alive through winter. Black bears in Alberta are typically in their dens by the start of November. Depending on the spring weather, the bear will emerge from the den in either April or May. Females with cubs tend to go down for the winter early and emerge late, while for males it’s the opposite.

Females mate in mid-summer, but the fertilized eggs don’t implant on the uterine wall and start developing until late fall. Females give birth while in the den, typically in early February, to two to three cubs on average. The mother will care for her cubs until their second summer, when they become independent, after which she’ll breed again.

In Alberta, the black bear lives in the shadow of the grizzly. The grizzly bear is generally larger, but this isn’t always reliable, as a male black bear can be larger than a small female grizzly. Both species have small, round ears, but the face of a black bear is longer and more dog-like than the short snout and wide head of the grizzly bear. A grizzly has a prominent shoulder hump, which the black bear lacks, and fur colour is far less variable between individual grizzlies. Grizzly claws are long and straight for digging, while black bear claws are hook-shaped for climbing, which the black bear does readily to either access food or seek shelter from predators. Grizzly bears have been known to prey on black bears.

The black bear is a forest-dwelling species, though it can sometimes be spotted in open fields adjacent to wooded areas. Like grizzlies, black bears will make scratch marks on tree trunks to communicate with other bears. In Alberta the black bear can be found just about anywhere except the grasslands, though it is most common in the more remote parts of the boreal forest, foothills, and mountains. Keep an eye out for it along wooded roads and trails where good forage is available. Black bears are more tolerant of humans than grizzlies, and will approach campsites, cabins, and towns if there’s food to be had.

Agricultural development has made the black bear somewhat scarce in the Central Parkland Subregion, but it seems to be relatively abundant in the Peace River Parkland of the northwest. In places where towns and farmland dominate the landscape, black bears often use wooded river valleys as natural highways to move from one suitable location to the next. Occasionally, this includes the bustling North Saskatchewan River valley of Edmonton.

The relationship between humans and black bears has been a tense one since the early days of European settlement. Nevertheless, it has been reasonably successful in adapting to human development and is currently listed as “Secure” in Alberta. Non-habituated black bears are generally afraid of people, avoiding us when they can and running away at the sign of our approach. Consequently, attacks on humans are very rare. Conflict between people and black bears is most often centred around food. Guided by their sharp sense of smell, intelligence, and curiosity, black bears are attracted to garbage dumps and unsecured food items. Worse still, sometimes people deliberately feed bears.

Preventing conflict between bears and humans before it happens is in the best interest of both species. Securing food and waste out of reach and practising appropriate agricultural methods in bear country is now widespread in Alberta. This, combined with better education on the dangers of feeding wildlife, is helping to reduce conflict between bears and humans. If we keep the black bear wild and give it plenty of wilderness to exist in, we can coexist peacefully well into the future.

Nick Carter is a writer, photographer, and naturalist from Edmonton. From birds and bugs to flowers and fossils, Nick is always seeking out the natural wonders of this province and sharing his enthusiasm with others.

Read the Original Article for this Post

For a richer reading experience, view this article in the professionally designed online magazine with all images and graphs in place.

This article originally ran in the Spring 2024 issue of Nature Alberta Magazine (Vol. 54 | No. 1).