Avian Influenza: A New Chapter in an Old Book

22 April 2024

BY MARGO PYBUS

Avian influenza is an ancient virus. It coevolved naturally in wild waterfowl over millennia — perhaps ever since dinosaurs started developing feathers. But our view of avian influenza as a disease agent shifted dramatically in spring 2022, as Mother Nature provided something never seen before in North America. There was a dramatic change in the ancient relationship between avian influenza virus (AIV) and the birds in which it lives, and the final outcome has yet to be revealed.

As we saw with COVID-19, viruses can change a lot! But some do so more than others. Influenza viruses are among the most changeable, and the strains of this virus in wild birds are constantly mixing and reassorting in a genetic melting pot around the world. Given the virus’ lengthy existence, genetic variation in AIV is extensive and can change rapidly. The predominant form of AIV can differ at continental, flyway, regional, and local levels. Data collected by the Canadian Wildlife Service from waterfowl across the prairies in the 1970s and 1980s revealed differences in the virus from year to year, month to month, species to species, week to week, and pond to pond. For example, the predominant form in mallards on one pond in one time period could differ from that in mallards on a different pond in the same time period, or differ from that in blue-winged teal on the same pond.

What Changed in 2022?

Normally the relationship between AIV and wild waterfowl is benign: the virus gains a place to live and reproduce but does not harm infected birds. However, in 2022 a novel strain of AIV — a specific form of H5N1 — was detected in dead wild geese and ducks during spring migration on all four North American flyways. Mortality was widespread across Canada and the U.S., from Atlantic to Pacific, from the Gulf of Mexico to the boreal forest.

The H5N1 AIV wave hit Alberta in early April 2022. Within a few days, Fish and Wildlife office phone lines lit up with sick and dead bird reports, largely snow geese in southern Alberta. But very quickly, most of central and east-central Alberta was awash with sick and dead snow geese and a few Canada geese. Infected geese were a bonanza for avian predators and scavengers, but the free food came with a high price. We received reports of significant numbers of sick or dead red-tailed hawks, great horned owls, crows, magpies, and a few peregrine falcons. Many, many owl and hawk nests were empty in 2022. At the same time, striped skunks displayed strange neurologic behaviour. In April and May 2022, more than 80 sick or dead skunks were reported from the same area where dead snow geese littered the landscape in central Alberta. We confirmed H5N1 in a sample of these skunks.

Infected birds and mammals displayed severe neurologic signs, including head tremors, weak necks, incoordination, and clouded eyes. Many raptors and corvids fell out of trees and died. Many skunks had severe seizures and convulsions before they died.

Through June and July of 2022, it was relatively quiet, although the virus showed up in a few cormorant and grebe colonies, with devastating effects on juveniles in some locations. During fall migration, a few individual ducks and geese tested positive for H5N1 but there was no widespread mortality. However, the outbreak continued through the winter in pockets of Canada geese that used open water in parts of southern Alberta, along with a few scavengers that ate the dead geese.

Overall, in 2022 we detected AIV (specifically North American HPAI H5N1) in a wide range of wild bird species, plus skunks and a few young foxes. Mortality was greatest in snow geese, great horned owls (adults and juveniles), red-tailed hawks, and crows. The same virus was detected in commercial and backyard poultry flocks involving approximately 1.4 million domestic birds across Alberta. It was a widespread and very “hot” form of AIV.

What Happened in 2023?

In an avian influenza context, spring migration and summer 2023 came and went with no detected mortality associated with the new AIV in wild birds or mammals (or poultry) in Alberta, nor anywhere across western regions of Canada and the U.S. There was a minor flurry of dead Canada geese with H5N1 during fall migration and among geese that spent early winter on open waters in southern Alberta, but not nearly the level of mortality seen in the previous year. Six infected skunks were also found in areas with dead Canada geese.

What Comes Next?

Spread of the deadly form of AIV fully reflects the interconnected nature of wild bird populations around the world. It initially began as a form of H5N1 that killed wild birds in Asia in 2006, which then spread to Europe and Africa. Eventually, it crossed over to North America, where it became a unique North American H5N1 against which wild birds here had no innate immunity to control the virus. As western hemisphere bird populations overlap, the virulent form of AIV systematically continued south through Mexico, Central America, South America and eventually, in October 2023, to bird colonies in isolated islands in the Antarctic region.

An H5N1 form of AIV still exists in wild waterfowl, mainly in mallards, but following the initial outbreak event, the mortality rate has declined. The genetics of the virus may be changing to something less pathogenic (after all, AIV is designed to live in harmony with wild ecosystems). And no doubt the protective immunity in wild ducks and geese also responds to limit the virulent form of H5N1. However, we can anticipate that the genetics of AIV will continue to percolate in its melting pot of wild bird populations.

Where things go from here will depend on what Mother Nature comes up with next.

For more information about AIV in Alberta, visit alberta.ca/avian-influenza-in-wild-birds.aspx and for Canadian data go to cwhc-rcsf.ca/avian_influenza.php

Margo Pybus is the Provincial Wildlife Disease Specialist with Alberta Fish and Wildlife. She holds a PhD in Wildlife Parasitology from the University of Alberta and is an adjunct professor in the Department of Biological Sciences at the University of Alberta.

Read the Original Article for this Post

For a richer reading experience, view this article in the professionally designed online magazine with all images and graphs in place.

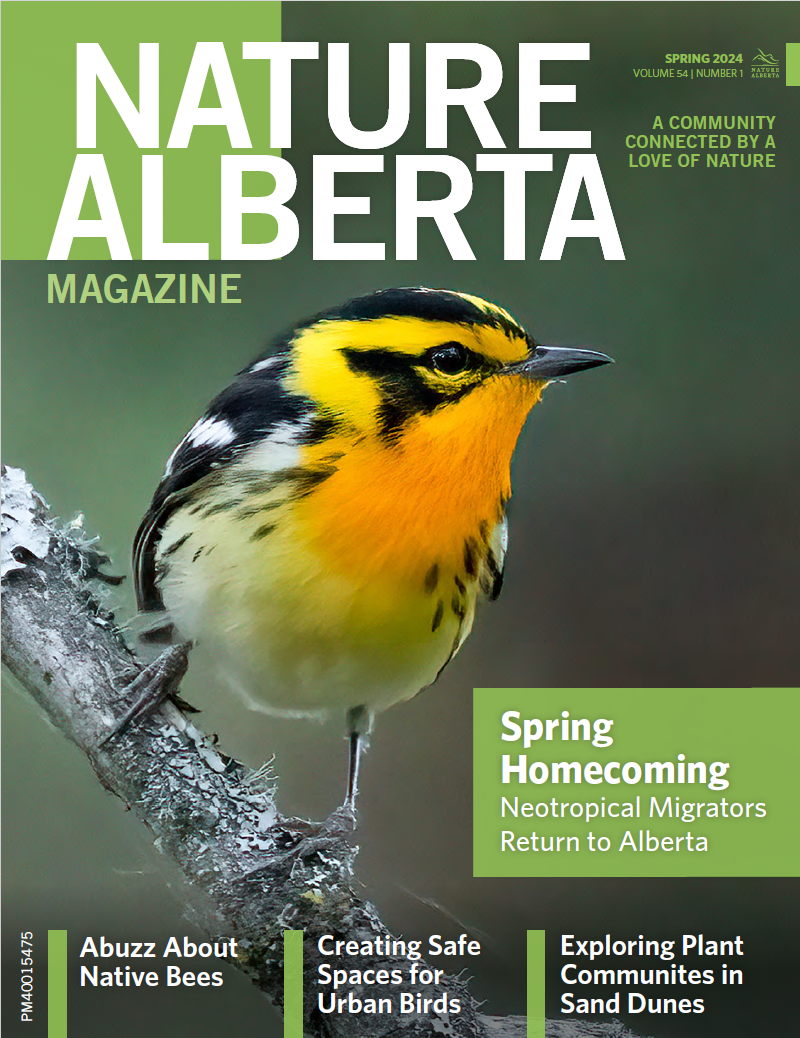

This article originally ran in the Spring 2024 issue of Nature Alberta Magazine (Vol. 54 | No. 1).