Citizen Science

Citizen science entails sharing and summarizing observations made by amateur naturalists. Having many “eyes and ears” studying nature helps advance our understanding of species distributions and trends, supporting their conservation. For example, the best information available on long-term changes in bird populations comes from the Breeding Bird Survey, which is entirely based on contributions from amateur birders. Taking part in citizen science programs is also a great way to get out and experience nature.

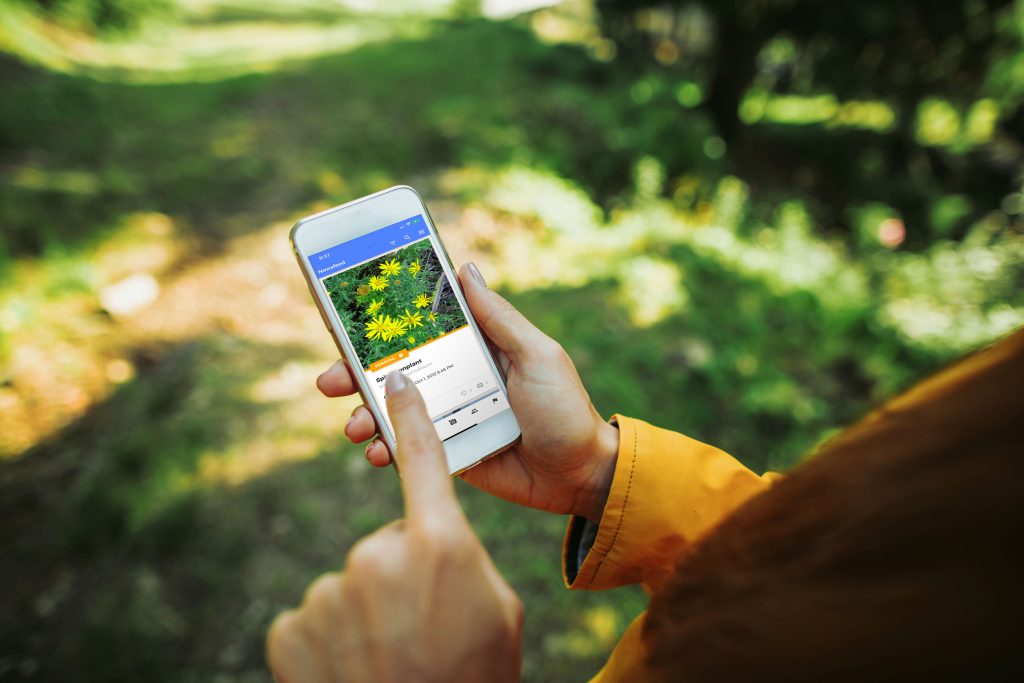

New smartphone apps make it easy for everyone to participate and, consequently, there has been tremendous growth in the citizen science community over the past few years. On eBird alone, there have been over 80 million checklists submitted to date, recording more than one billion bird observations.

If you are new to citizen science, be sure to look through our Getting Started materials, below. Here you will find a general introduction to citizen science as well as tutorials for eBird and iNaturalist, the two largest projects. Once you’ve become oriented you can look for a project that aligns with your interests and get involved. We’ve organized the available projects into taxonomic groups — there is something here for everyone.

Getting Started

Citizen science provides an opportunity for naturalists, both novice and experienced, to meaningfully contribute to science and the conservation of biodiversity. This is what it’s all about. As naturalists, we love to watch wildlife, but if we want wild species to remain viable we need to actively contribute to their conservation. Participating in citizen science is a great way to accomplish this.

The new smartphone apps that citizen science projects now use to record observations also help naturalists directly. At the most basic level, they provide an efficient way of making and storing observations, largely replacing the handwritten checklists of the past. The quality of observations has also increased, through the inclusion of photographs, sound recordings, automatic time stamps, and GPS locations.

Some apps are also beginning to assist with species identification in the field, using image and sound recognition algorithms derived from citizen science databases (e.g., Seek and Merlin). These identification tools are still at an early stage of development, but even now they are a great help to novice naturalists.

The citizen science databases are also useful reference sources for naturalists. The larger platforms provide excellent resources for learning about species, and their map products are valuable for trip planning.

Citizen science is the practice of engaging the public in scientific projects that produce reliable information usable by scientists, decision-makers, and the public. In the field of conservation, most citizen science projects focus on broad-scale species monitoring. These projects provide information on species abundance, species distribution, migratory patterns, and the timing of natural processes such as flowering. Some projects focus on monitoring aquatic and terrestrial habitat quality. In addition, researchers and resource managers sometimes recruit volunteers to help collect data for specific research studies.

The core strength of citizen science is the large number of observers it engages. This complements the main weakness of conventional science, which is limited capacity. Scientists are very good at collecting high-quality data, but there just aren’t that many of them. Placing literally millions of additional observers in the field makes a tremendous difference in what can be achieved.

Through citizen science, we can monitor across vast spatial scales and over extended time frames. We can also track rare species and species that are generally overlooked through conventional monitoring programs. Moreover, through the new phone apps, which provide photographs, sound recordings, GPS locations, and time stamps, the value of citizen observations for scientific applications has been greatly enhanced.

To learn more about the science behind citizen science, have a look at this video presentation by our Executive Director, Dr. Richard Schneider.

With the rising profile of citizen science in recent years, the number of projects has greatly increased. This can present a challenge for budding citizen scientists. How do you choose which project to participate in? Obviously, there has to be a good fit with your interests. Beyond that, consideration should be given to the value of the project to science and conservation.

Some citizen science projects are highly structured and are designed to collect data for a specific purpose. Typically, the organization or individual that initiates the project also leads the analysis of the data and the application of the findings. Structured projects are characterized by standardized methods for making observations.

Well-designed structured projects tend to score highly in terms of their contribution to science. The Breeding Bird Survey provides a good example. Each spring, volunteers count birds along a series of fixed survey routes using a standardized observation protocol. The Canadian Wildlife Service, which oversees the program in Canada, analyzes the data and generates regular reports on the state of birds in Canada, which wildlife managers rely on. No better dataset exists for tracking changes in bird abundance over time.

There are also citizen science projects that are relatively unstructured. Generally, the intent is to build a database of observations without explicitly defining what the data will be used for. Projects may impose some requirements, such as requiring a photograph or limiting which species are to be included. But participants are otherwise free to make observations whenever and wherever they please.

Some of the larger unstructured projects, such as iNaturalist and eBird, contribute meaningfully to science despite the opportunistic nature of the observations. In this case, size is a key factor — both projects are global in scope and each has millions of participants. Never in the history of science has so much information been collected about so many species. The large number of observations permits meaningful insights to be made, despite variability among observers.

Though the iNaturalist database is not well suited for monitoring trends, it excels at describing species distributions, especially of uncommon species and invasive species, which are difficult to monitor using conventional methods. In the case of eBird, the checklist approach permits the estimation of both distribution and abundance. Furthermore, because observations are submitted all year long, the data are useful for studying migratory patterns. Given their large size, both projects have attracted the attention of researchers and wildlife managers, who increasingly look to these databases to inform their work.

Despite the inherent benefits of large projects, the value of small, local projects should not be discounted. A small project may have very high conservation value if it is focused on gathering data for a specific local application. In other words, purpose and application are overriding factors.

Beyond these general concepts, there are six specific criteria worth considering when choosing projects to participate in:

- Accessibility. Projects should facilitate the broad, public sharing of information (at no charge). You don’t want the fruits of your labour mouldering in an obscure database that few people know about.

- Data products. Further to point 1, projects that analyze the incoming data and provide products such as distribution maps and summary reports are preferable to projects that just store the data. Note that most data downloads are actually from members of the public who use the information for educational purposes and for informing local conservation efforts.

- Application. In conservation, the fundamental role of science is to support management decisions and guide conservation actions. Therefore, projects that have the attention of researchers and resource managers are preferred over those that do not. The more direct the connection between observations and their management application, the better.

- Spatial and temporal scope. Species do not respect administrative boundaries. Therefore, all else being equal, a national or global project is preferable to one that is local in scope. Similarly, projects that collect observations all year long are preferred over projects that provide only a snapshot at a particular time of year.

- Data quality. Projects that have standardized protocols for making observations generate higher-quality data than projects that do not. So do projects that check the validity of species identifications submitted by observers. High-quality data facilitates the ability of researchers to draw meaningful insights from the observations.

- Data security. It is an unfortunate reality that citizen science initiatives sometimes shut down after a period of time, typically because of a lack of funding, a change in an organization’s priorities, or the loss of key people. Some projects have also lost data (mainly in the era before cloud-based storage). Therefore, consideration should be given to the long-term viability of the project and its ability to store data reliably.

Besides selecting projects with high conservation value, there are several other things you can do to maximize the value of your citizen science efforts. To begin, you can work on improving the quality of your observations. For example, if you are using eBird, make an effort to improve your bird identification skills and be sure to submit complete checklists rather than just casual observations. Incomplete checklists are generally excluded from the statistical analysis of eBird data. If you are submitting photos to iNaturalist, make sure your pictures are of good quality and capture the elements that are needed for species identification (e.g., both leaves and flowers). Remember, individual observations can include multiple photographs from different angles.

It’s also useful to travel off the beaten path when making observations. Citizen science contributions tend to cluster around urban centres, leaving data gaps in more remote areas. Your observations will be more valuable if they serve to fill these spatial gaps. Similarly, when using iNaturalist it is helpful to emphasize uncommon and invasive species, since they are most in need of monitoring.

Lastly, try to move up the citizen science “ladder” as you become more experienced. For example, once your bird identification skills have improved using eBird, you might consider taking on a Breeding Bird Survey route. There is always a need for new survey volunteers, and the contribution to bird conservation is very high with this program. You can also look for opportunities to become a “citizen steward” by supporting the conservation of a favourite natural area, or advocating for nature by writing or phoning decision-makers about key conservation issues.

Our Getting Started with eBird page provides an overview of this remarkable initiative along with tutorials to get you going.

iNaturalist is the world’s largest citizen science platform devoted to general biodiversity. There are now more than 2 million iNaturalist users who have collectively contributed close to 100 million observations. Behind the scenes, a community of volunteer naturalists works to help identify the species submitted to the database.

All of the information gathered is made available to the public at no charge through the iNaturalist website, which can be searched by species, location, date, or by specific project. This website is a great place to learn about species or places you are interested in. Because of the massive size of the iNaturalist database, it has also attracted the attention of researchers and wildlife managers, ensuring that the data contribute to conservation.

An iNaturalist observation consists of a photograph or a sound recording of an individual plant or animal. These observations can be made in the field using the iNaturalist smartphone app (no data connection is required). The app automatically adds a time stamp and GPS location, which greatly enhances the value of the observations to researchers. Observations can also be added or edited on a computer at home.

Many organizations, including Nature Alberta, use iNaturalist for local citizen science projects. In such cases, an organization sends an invitation to volunteer naturalists to collect data for a specific purpose. For example, this could involve surveying the biodiversity in a specific area or mapping the distribution of a given species. Several of the citizen science projects listed below are iNaturalist projects of this type.

The iNaturalist mobile app is easy to use. Get started by viewing this iNaturalist Tutorial

For help with navigating the iNaturalist website, have a look at this tutorial.

If you have questions about iNaturalist, try the iNaturalist FAQ

Bird Projects

Birds of Alberta is an iNaturalist project focusing specifically on birds. It is best suited to casual observations—that is, birds you happen to encounter when not actively birding. These observations help to describe the diversity of bird species in the province and how they are distributed.

To participate, just take a photo or sound recording of any bird you encounter using the iNaturalist app, add the species name if you know it, and press the "Submit" button. Your observation will automatically be added to the project. You can view the tallied results anytime on the project website. If you are new to iNaturalist, view our Getting Started guide at the top of this page.

If you are actively birding—that is, keeping track of all the birds you see or hear on an outing—then it is best to use eBird to record your observations. This is because eBird is designed to collect "count" data, which iNaturalist is not. Count data from completed checklists can be statistically analyzed to estimate species abundance and trends, and not just distribution. Therefore, this approach is more valuable for science and conservation applications.

The Breeding Bird Survey is a citizen science program that produces the best information available on long-term trends in bird abundance across North America. This dataset is relied on heavily by researchers, wildlife managers, and others to support bird conservation efforts.

The way the survey works is that each spring volunteers count birds along a series of fixed survey routes using a standardized observation protocol. The Canadian Wildlife Service oversees the program in Canada. It also analyzes the data and generates regular reports, such as the State of Birds in Canada.

There are 203 Breeding Bird Survey routes in Alberta, and there is always a need for new volunteers to participate. Bird identification experience is a requirement, though if you are still working on your identification skills you can work as an assistant until you are ready to take on a route of your own.

To learn more about this important citizen science program and to get involved, visit the Breeding Bird Survey website.

If you regularly visit a Canadian lake, you can participate in the Canadian Lakes Loon Survey, run by Birds Canada. This program has been tracking chick hatching and survival of common loons since 1981. Participants dedicate at least three days, visiting their lake once in June (to see if loon pairs are on territory), once in July (to see if chicks hatch), and once in August (to see if chicks survive long enough to fledge).

Participants often work as stewards within their lake communities, advocating for better boating, fishing, or shoreline practices, protecting and supporting not only loons but the many other aquatic species that share our waterways.

To learn more about the loon survey and to get involved, visit the Canadian Lakes Loon Survey website.

Nightjars in Alberta include the common nighthawk, found all across the province, and the common poorwill, found in some parts of southern Alberta. Conducting a Nightjar Survey is easy – anyone with good hearing and a vehicle can participate!

- Each route is a series of 12 road-side stops

- Each route needs to be surveyed once per year between June 15 and July 15

- Each survey starts 30 minutes before sunset

- At each stop, you will listen quietly for nightjars for six minutes and record information about your survey

Email Andrew Coughlan at acoughlan@birdscanada.org for more information and to register for your route.

The Christmas Bird Count started in 1900 and is the longest running citizen science project in North America. Christmas Bird Counts are conducted within defined areas (count circles) on a single day between Dec 14 and Jan 5. Many are organized by Nature Alberta Member Clubs! By participating you will contribute data that helps researchers assess population and distribution trends of birds.

You can also participate as a feeder watcher, from the comfort and warmth of your own home, or as a bush beater by coordinating efforts with others.

The eagle count at Kananaskis, run by the Rocky Mountain Eagle Research Foundation, has been running for over 30 years. But many of the older observers are no longer able to help out, so there is a need for dedicated people to help fill their ranks. Everyone who shows up with a pair of binoculars to help spot birds is appreciated, but what they need most are people who will commit to a regular schedule, first as an Assistant Observer, and later as a Principal Observer. Learn more.

eBird is a citizen science platform that birders use to record their bird observations wherever they travel all year long. If you are new to eBird, have a look at our Getting Started with eBird guide.

There are also birding events linked directly to eBird. These include the Global Big Day (in May) and the October Big Day. We will post the dates of these events in the Citizen Science News section of this webpage. You can also visit the eBird website for more information.

Other bird-related citizen science projects are beginning to use eBird for their events, including the Christmas Bird Count, the Great Backyard Bird Count (in February), and the May Bird Count. This is a work in progress.

The May Bird Count is a component of the annual May Species Count. This project was initiated in 1976 to track bird populations across Alberta at a fixed time of year, providing insight into population trends over time. It was also intended to encourage cooperative efforts toward understanding local natural history. Learn more about this project, including how to participate, on the May Bird Count web page.

Project FeederWatch is a November-April survey of birds that visit backyards, nature centers, community areas, and other locales in North America. You don’t even need a feeder! All you need is an area with plantings, habitat, water or food that attracts birds. The schedule is completely flexible. Count your birds for as long as you like on days of your choosing, then enter your counts online. Your counts allow you to track what is happening to birds around your home and contribute to a continental dataset of bird distribution and abundance.

To learn more about this program and to get involved, visit the Project Feeder Watch website.

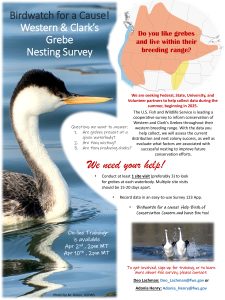

The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service is seeking Federal, State, University, and Volunteer partners to help collect data during the summer, beginning in 2025.

The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service is seeking Federal, State, University, and Volunteer partners to help collect data during the summer, beginning in 2025.

The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service is leading a cooperative survey to inform conservation of Western and Clark’s Grebes throughout their western breeding range. With the data you help collect, they will assess the current distribution and nest colony success, as well as evaluate what factors are associated with successful nesting to improve future conservation efforts.

Questions they want to answer:

1. Are grebes present at a given waterbody?

2. Are they nesting?

3. Are they producing chicks?

You Can Help!

- Conduct at least 1 site visit (preferably 3) to look for grebes at each waterbody. Multiple site visits should be 15-20 days apart.

- Record data in an easy-to-use Survey 123 App.

- Birdwatch for a cause! HelpBirds of Conservation Concern and have fun too!

To get involved, sign-up for training (Apr 10, 2025), or to learn more about the survey, please contact:

Deo Lachman: Deo_Lachman@fws.gov or

Adonia Henry: Adonia_Henry@fws.gov

Mammal Projects

The Alberta Community Bat Program is a citizen science project run by the Wildlife Conservation Society of Canada as part of a national bat conservation effort. The project is intended to raise awareness of bat conservation issues, provide information to help residents responsibly manage bats in buildings, and to collect data needed to monitor and better understand bats in the province.

Part of the project involves monitoring bat roosts. Maternity roosts are locations where female bats raise their pups during the summer. If you come across an active roost, please report it using the form available on the Community Bat Program website.

The program also includes an iNaturalist project for recording observations of individual bats. The intent is to build a database that will help describe the distribution, habitat use, and seasonal timing of bat activity in Alberta. Simply submit your bat observations to iNaturalist and they will automatically be added to the Bats of Alberta project. If you are new to iNaturalist, view our Getting Started guide at the top of this page.

The Canadian Bat Box Program takes citizen science to the next level where people can register their bat box, install a datalogger to record internal temperature and humidity, swab the box to test for white-nose syndrome, and submit guano samples. Join the Canadian Bat Box Study here: https://cwf-fcf.org/en/explore/bats/bat-survey-1.html

The Edmonton Urban Coyote Project began in 2009 in the lab of Dr. Colleen Cassady St. Clair, Professor of Biological Sciences at the University of Alberta. The project aims to conduct research and provide information that will promote coexistence between people and wildlife. Read more about this project here.

In Fall 2023, M.Sc. student Abby Keller will use remote cameras with track and hair tubes to study the attraction to birdseed in residential yards by coyotes and their prey. If you would like to participate, feed birds from a suspended feeder, and have a fenceless yard that backs on a natural area, please contact coyotes@ualberta.ca. To view more details, click here.

Franklin’s ground squirrel was once common in central Alberta; however, it has become increasingly rare over the years. Nature Alberta initiated a project and is collaborating with Dr. Jessica Haines at MacEwan University to gather more data on this species to help determine whether it is in decline. To learn more and to participate in this project, visit the project's web page.

Thirteen-lined ground squirrels are uncommon in Alberta and their official status is "undetermined." Nature Alberta has initiated a citizen science project to help fill information gaps about their distribution and status. If you spot one of these elusive squirrels, please take a photograph and submit your observation to iNaturalist. To learn more, visit the iNaturalist project page.

s this project, visit the project's web page.

s this project, visit the project's web page.

Amphibian & Reptile Projects

The Alberta Volunteer Amphibian Monitoring Program (AVAMP) is a citizen science program run by the Alberta Conservation Association. It encourages participants to learn about frogs, toads, and salamanders and help conserve their populations by reporting observations. AVAMP data is forwarded to the Government of Alberta for entry into its Fisheries and Wildlife Management Information System database. This database supports appropriate conservation and management of Alberta’s wild species and their habitats.

To learn more about the program and to get involved, visit the AVAMP website.

The Alberta Amphibian and Reptile Conservancy has initiated an iNaturalist project to track all amphibian and reptile sightings in Alberta. In doing so, they hope to connect the public to these endearing, but often misunderstood animals. The information collected may be useful for the creation of a field guide, research, and conservation management.

Because this is an iNaturalist project, participating is easy. Just take a photo or sound recording of any amphibian or reptile you encounter using the iNaturalist app, add the species name if you know it, and press the "Submit" button. Your observation will automatically be added to the project. You can view the results anytime on the project website. If you are new to iNaturalist, view our Getting Started guide at the top of this page.

Insect Projects

This is an iNaturalist project that aims to document all species of Coleoptera (beetles) in Alberta. This information will help build a photo database of what species exist provincially and help with species identification.

Because it is an iNaturalist project, participating is easy. Just take a photo of any beetle you encounter using the iNaturalist app, add the species name if you know it, and press the "Submit" button. Your observation will automatically be added to the project. You can view the results anytime on the project website. If you are new to iNaturalist, view our Getting Started guide at the top of this page.

In 2017, the Alberta Native Bee Council launched a citizen science bumble bee box monitoring program. Similar to bird houses, bumble bees may or may not colonize a bumble bee nest box. This monitoring program seeks to determine the rate of box use, as a measure of bumble bee population status. Visit the bumble bee box monitoring program website to learn how to build a bee box and how to monitor it.

Bumble Bee Watch is a collaborative effort to track and conserve North America’s bumble bees. This community science project helps researchers determine the status and conservation needs of bumble bees and helps them locate rare or endangered populations. It's also a great way to learn about bumble bees and their ecology.

Bumble Bee Watch needs your help. Because bumble bees are widely distributed, the best way to keep track of them is with a group of volunteers across the country equipped with cameras. With any luck, you might help us to find remnant populations of rare species!

To learn more about this project and to get engaged, visit the Bumble Bee Watch website.

This is an iNaturalist project that aims to document all species of Odonata (dragonflies and damselflies) in Alberta. This information will help build a database of what species exist provincially.

Because it is an iNaturalist project, participating is easy. Just take a photo of any dragonfly or damselfly you encounter using the iNaturalist app, add the species name if you know it, and press the "Submit" button. Your observation will automatically be added to the project. You can view the results anytime on the project website. If you are new to iNaturalist, view our Getting Started guide at the top of this page.

Butterfly watchers experience amazing observations all the time. The goal of eButterfly is to gather this incredible individual experience in the form of checklists, archive it, and freely share it to power new data-driven approaches to science, conservation and education. Like iNaturalist, the data are submitted to the Global Biodiversity Information Facility, where it is available to researchers and others.

At the same time, eButterfly provides tools that make butterfly watching more rewarding. From being able to manage lists and photos, to seeing real-time maps of butterfly distribution, or the ability to discuss your sightings with others; this program strives to provide the most current and useful information to the community.

To participate in this program, visit the eButterfly website.

This is an iNaturalist project that aims to document all species of Lepidoptera (moths and butterflies) in Alberta. This information will help build a database of what species exist provincially.

Because it is an iNaturalist project, participating is easy. Just take a photo of any moth or butterfly you encounter using the iNaturalist app, add the species name if you know it, and press the "Submit" button. Your observation will automatically be added to the project. You can view the results anytime on the project website. If you are new to iNaturalist, view our Getting Started guide at the top of this page.

The annual Winter Bug Count was started by John Acorn in 2011 to document Arthropods - insects, spiders, and crustaceans such as sow bugs - in Alberta and Saskatchewan through December, January, and February. Accepted species include any free living arthropod indoors or outdoors and exclude pets, specimens, or pet food. View the 2022-2023 Winter Bug Count results here. You can contribute your own observations to this year's Winter Bug Count using iNaturalist. View detailed step by step instructions to participate here.

Plant & Fungi Projects

The May Plant Count is open to anyone with an interest in plants and flowering. The survey takes place between May 25 – 31 and focuses on documenting the flowering status of native plant species across Alberta. To learn more about the count and to participate, visit the May Plant Count webpage.

This is an iNaturalist project that aims to document all species of mushrooms, mosses and lichens in Alberta. Because it is an iNaturalist project, participating is easy. Just take a photo of any mushroom, moss, or lichen you encounter using the iNaturalist app, add the species name if you know it, and press the "Submit" button. Your observation will automatically be added to the project. You can view the results anytime on the project website. If you are new to iNaturalist, view our Getting Started guide at the top of this page.

By reporting when certain plants bloom and leaf out in spring, Albertans contribute vital information for climate change studies. The speed of spring plant development is controlled mainly by temperature, and there is evidence that warming winter and spring temperatures are already resulting in earlier appearances of flowers. If you have an interest in flowers and would like to participate in this study, visit the Plantwatch webpage for more information. You can also read about past findings in Plantwatch newsletters.

General Biodiversity Projects

Alberta is home to a rich diversity of species. However, natural landscapes supporting a full complement of native species have become increasingly rare in Alberta because of widespread agriculture and industrial development. Therefore, parks and protected areas play a critical role in biodiversity conservation.

The Alberta Parks iNaturalist project seeks to document the biodiversity that exists within Alberta's park system. The intent is to support conservation efforts within the parks and to draw attention to the important role that parks play in supporting biodiversity.

The first step in contributing to this project is to visit and enjoy Alberta's parks. While there, make an effort to submit observations of some of the species you encounter to iNaturalist . As long as the observation is made within a park, it will automatically be added to the project. If you are new to iNaturalist, view our Getting Started guide at the top of this page.

Rather than sending in the standard photo of an elk on the side of the road, challenge yourself to find something new each visit. There have been over 3,500 species of plants and animals identified to date, so there is no shortage of options.

You can view the tallied results anytime on the project website. To learn more about Alberta parks and to plan your visit, check out the Alberta Parks website.

The Alberta Biodiversity Challenge invites Albertans to take part in a photo BioBlitz in June using the iNaturalist app. Seven cities in Alberta are competing to see which can generate the most observations during the event. In 2023, the BioBlitz was expanded to also include Alberta's national and provincial parks.

Participating is easy. Simply upload your photos of birds, plants, mammals, moss, lichen, mushrooms and insects to iNaturalist. Your contributions will be used to help us understand more about the species that call our region home. To learn more visit the Biodiversity Challenge Webpage.

The 2025 Biodiversity Challenge is scheduled for Thursday, June 12 to Sunday, June 15.

The City Nature Challenge is a global urban biodiversity “contest”, where cities compete against one another to monitor biodiversity within their cities. The Challenge invites urban Albertans to take part in a photo BioBlitz using iNaturalist.

Between April 25 - April 28, 2025, join our region’s naturalists, species experts, and environmental groups in documenting as many species as you can! Simply upload your photos of birds, plants, mammals, moss, lichen, mushrooms and insects to iNaturalist. Your contributions will be used to help understand more about the species that call our region home.

Visit citynaturechallenge.org for more information.

The Early Detection and Distribution Mapping System is a citizen science initiative for documenting invasive species and pest distribution. Early detection and response are critical to successfully managing invasive species. You can report sightings either on the EDDMapS website or via the EDDMapS smartphone app, available for both iPhone and Android.

If you encounter an invasive species but do not have the EDDMapS app on your phone, you can also submit observations via iNaturalist. These observations contribute to the iNaturalist Alien Vascular Plants of Alberta project. However, sending information about invasive species directly to control agencies via the EDDMapS app is preferable when practical.

To learn more about invasive species in Canada, as well as control measures, visit the Invasive Species Centre website.

The Key Biodiversity Areas of Canada iNaturalist project is a fantastic gateway to learning more about the broader biodiversity within Key Biodiversity Areas (KBA). The project is a hub connecting the iNaturalist pages for all confirmed KBAs in Canada and more KBAs will be added to the project regularly.

Join the main KBAs of Canada project and your favorite individual site projects to save the project to your personal iNaturalist profile, and keep updated on news and sightings in the KBAs. Join a project using the button to the right of the “About” section at the top of project pages.

Alberta Migratory Bird Sanctuaries is a Nature Alberta project to encourage nature appreciation, wildlife observations, and participation in citizen science on iNaturalist at protected migratory bird sanctuaries. In Alberta we have 3 sanctuaries: Saskatoon Lake, Gaetz Lakes, and Inglewood Migratory Bird Sanctuaries.

Join the Alberta Migratory Bird Sanctuaries project to save the project to your personal iNaturalist profile to keep updated on sightings in all MBSs. Join a project using the button to the right of the “About” section at the top of the project’s page.

Alberta is home to a rich diversity of species; however, many of these species have declined because of habitat loss and other factors. Almost 200 species now are listed as endangered, threatened, or of special concern. You can support the management of these species by submitting observations to iNaturalist Canadian Species at Risk Project. Citizen science monitoring is of particular value for these species because their low population levels makes them challenging to monitor using conventional approaches. If you are new to iNaturalist, view our Getting Started guide at the top of this page.

To contribute to this project simply take a photo or sound recording of any species at risk you encounter and submit it to iNaturalist. If you are not certain of the species, submit it anyway. iNaturalist is supported by a community of naturalists that will help identify the species once the observation has been submitted. If it turns out that the species is not at risk, your observation will still contribute to the iNaturalist biodiversity database.

You can view the results anytime on the project website. To learn more about Alberta's species at risk, visit the Alberta government's Species at Risk website.

Aquatic Projects

Freshwater bivalves (clams and mussels) are declining due to habitat destruction. In Alberta, the current distribution and status of bivalves is largely unknown, as the taxon was last surveyed in the 1960s. Thus, a thorough provincial-wide survey of bivalves is warranted.

Please help us expand our knowledge of bivalves in Alberta by submitting high-quality images of mussels and clams to iNaturalist. Your observations are automatically added to the Bivalves of Alberta project. If you are new to iNaturalist, view our Getting Started guide at the top of this page.

LakeWatch is a volunteer-based water quality monitoring program offered to Albertans who are interested in collecting information about their local lake or reservoir. For more than 25 years, Alberta Lake Management Society technicians have assisted volunteers to test their lakes four times during the summer, collecting important data such as water temperature, clarity, a suite of water chemistry parameters, and invasive species. Once all of the data is collected we produce a LakeWatch Report for the lake which summarizes the data in an easy-to-understand manner. LakeWatch Reports can be used to educate lake users and guide water restoration and management efforts. If you are interested in having your lake monitored as part of the LakeWatch program, please contact info@alms.ca

The Summer LakeKeepers program is a citizen science program run by the Alberta Lake Management Society. Summer LakeKeepers allows volunteers to independently monitor lakes or reservoirs for parameters important to ecological health. Training manuals and monitoring equipment are sent to LakeKeepers to collect monthly data from their lake or reservoir. Data from Summer LakeKeepers is stored on DataStream.

The Winter LakeKeepers program is a citizen science program run by the Alberta Lake Management Society. This program equips and enables citizen scientists to independently monitor lakes or reservoirs for parameters important to ecological health while ice fishing. Contact the Alberta Lake Management Society to learn how you can get started monitoring your favourite lake under the ice. Data from Winter LakeKeepers is stored on DataStream.