Sand Dune Plant Communities of Northern Alberta

22 April 2024

BY PATSY COTTERILL

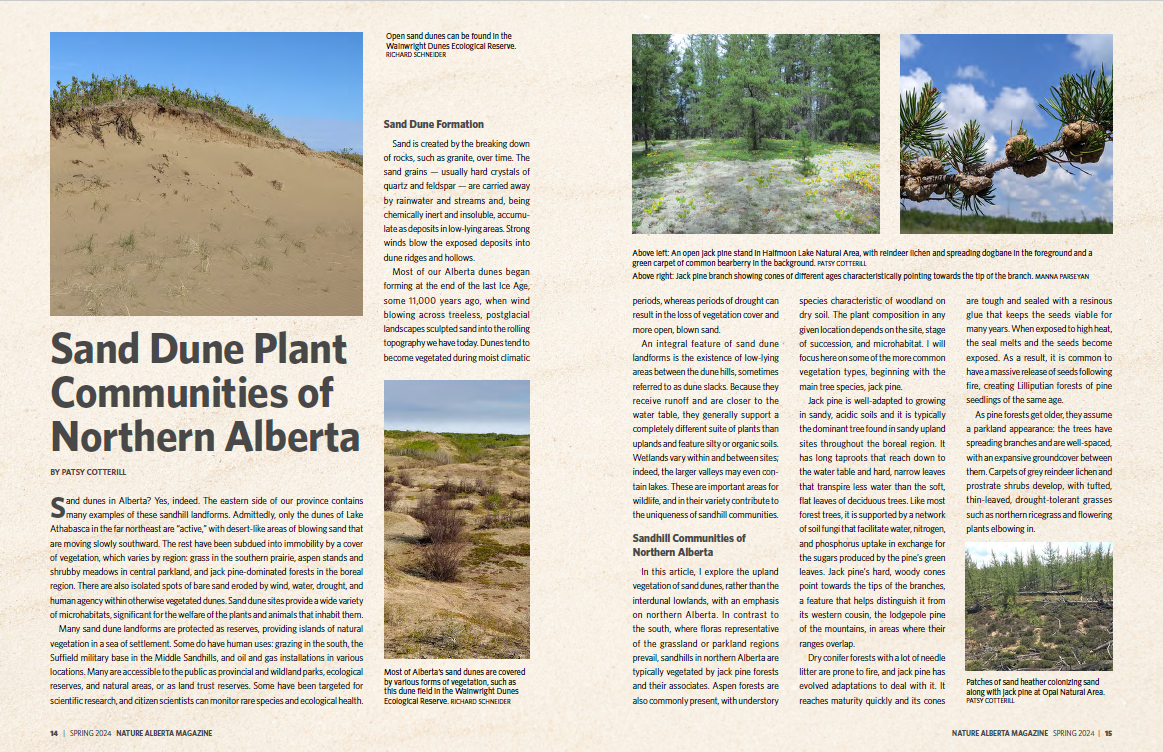

Sand dunes in Alberta? Yes, indeed. The eastern side of our province contains many examples of these sandhill landforms. Admittedly, only the dunes of Lake Athabasca in the far northeast are “active,” with desert-like areas of blowing sand that are moving slowly southward. The rest have been subdued into immobility by a cover of vegetation, which varies by region: grass in the southern prairie, aspen stands and shrubby meadows in central parkland, and jack pine-dominated forests in the boreal region. There are also isolated spots of bare sand eroded by wind, water, drought, and human agency within otherwise vegetated dunes. Sand dune sites provide a wide variety of microhabitats, significant for the welfare of the plants and animals that inhabit them.

Many sand dune landforms are protected as reserves, providing islands of natural vegetation in a sea of settlement. Some do have human uses: grazing in the south, the Suffield military base in the Middle Sandhills, and oil and gas installations in various locations. Many are accessible to the public as provincial and wildland parks, ecological reserves, and natural areas, or as land trust reserves. Some have been targeted for scientific research, and citizen scientists can monitor rare species and ecological health.

Sand Dune Formation

Sand is created by the breaking down of rocks, such as granite, over time. The sand grains — usually hard crystals of quartz and feldspar — are carried away by rainwater and streams and, being chemically inert and insoluble, accumulate as deposits in low-lying areas. Strong winds blow the exposed deposits into dune ridges and hollows.

Most of our Alberta dunes began forming at the end of the last Ice Age, some 11,000 years ago, when wind blowing across treeless, postglacial landscapes sculpted sand into the rolling topography we have today. Dunes tend to become vegetated during moist climatic periods, whereas periods of drought can result in the loss of vegetation cover and more open, blown sand.

An integral feature of sand dune landforms is the existence of low-lying areas between the dune hills, sometimes referred to as dune slacks. Because they receive runoff and are closer to the water table, they generally support a completely different suite of plants than uplands and feature silty or organic soils. Wetlands vary within and between sites; indeed, the larger valleys may even contain lakes. These are important areas for wildlife, and in their variety contribute to the uniqueness of sandhill communities.

Sandhill Communities of Northern Alberta

In this article, I explore the upland vegetation of sand dunes, rather than the interdunal lowlands, with an emphasis on northern Alberta. In contrast to the south, where floras representative of the grassland or parkland regions prevail, sandhills in northern Alberta are typically vegetated by jack pine forests and their associates. Aspen forests are also commonly present, with understory species characteristic of woodland on dry soil. The plant composition in any given location depends on the site, stage of succession, and microhabitat. I will focus here on some of the more common vegetation types, beginning with the main tree species, jack pine.

Jack pine is well-adapted to growing in sandy, acidic soils and it is typically the dominant tree found in sandy upland sites throughout the boreal region. It has long taproots that reach down to the water table and hard, narrow leaves that transpire less water than the soft, flat leaves of deciduous trees. Like most forest trees, it is supported by a network of soil fungi that facilitate water, nitrogen, and phosphorus uptake in exchange for the sugars produced by the pine’s green leaves. Jack pine’s hard, woody cones point towards the tips of the branches, a feature that helps distinguish it from its western cousin, the lodgepole pine of the mountains, in areas where their ranges overlap.

Dry conifer forests with a lot of needle litter are prone to fire, and jack pine has evolved adaptations to deal with it. It reaches maturity quickly and its cones are tough and sealed with a resinous glue that keeps the seeds viable for many years. When exposed to high heat, the seal melts and the seeds become exposed. As a result, it is common to have a massive release of seeds following fire, creating Lilliputian forests of pine seedlings of the same age.

As pine forests get older, they assume a parkland appearance: the trees have spreading branches and are well-spaced, with an expansive groundcover between them. Carpets of grey reindeer lichen and prostrate shrubs develop, with tufted, thin-leaved, drought-tolerant grasses such as northern ricegrass and flowering plants elbowing in.

The older trees often bear dense masses of twigs known as witches’ brooms. These signal an infestation with American dwarf mistletoe, a semi-parasitic plant that penetrates the bark of the host pine, tapping into its food- and water-conducting systems. It produces single-seeded berries that burst explosively when ripe, shooting the sticky seed out with a chance to find a new branch on which to germinate. Witches’ brooms provide shelter and nesting habitat for red squirrels and birds.

Jack pine forests are associated with a variety of understory plants depending on stage of succession and various microhabitat factors. In sandy areas free from erosion, it is common to find a crust of non-flowering plants, mosses, spikemoss, and lichens. Between rains, the crust is dry and crunchy to walk on and the mosses and lichens are dormant — an adaptation to drought. When wet, they turn green and soft, the leaves of the mosses unfurl, and photosynthesis kicks into gear. Lichens are an amalgam of fungi and photosynthesizing algae or cyanobacteria that allows these amazing organisms to grow in unfavourable habitats. (For an “enlichening” introduction to lichens, see Diane Haughland’s article in the Winter 2024 issue of Nature Alberta Magazine.)

Low shrubs of the heath family are also abundant inhabitants of jack pine forests; they too have characteristics that allow them to tolerate dry, sandy soils. Common bearberry (also known as kinnikinnick) has small, hard, evergreen leaves with shiny cuticles, which reduce water loss. It has well-developed taproots and spreads by trailing stems to form extensive patches, which also conserve moisture. Bearberry leaves are food for caterpillars of a rare moth and rare species of butterflies.

Another heath, velvet-leaved blueberry, occurs on dune uplands but flourishes best in the lower-lying areas or in aspen stands. It is unusual among heaths in being deciduous, losing its softly hairy leaves at the onset of winter. Its pink, bell-like flowers are too small for most bees to enter; instead, it is “buzz-pollinated” by bumblebees and andrenid bees, which vibrate their thorax muscles to shake out the pollen through the anther pores. The sweet, blue fruits are relished by a variety of mammals and birds.

Sand heather has a restricted distribution in the sandhills north of Edmonton and the far northeast, although it can occur in large numbers colonizing ground after fire. A heath-like, cushion-forming shrub with small, crowded leaves covered in hairs (all features that reduce water loss), it has attractive yellow flowers reminiscent of small roses. Research has unearthed another adaptation: nitrogen is scarce in sandy soils, but cyanobacteria live in “green sand” in the plant’s root zone and “fix” atmospheric nitrogen in the soil, making it available to the plant.

Rare and Uncommon Species

A number of rare and uncommon species grow in Alberta’s sandhills and, while they contribute little to vegetation cover, they are of interest in their rarity. Examples from the south include western spiderwort, sand flatsedge, and small-flowered sand-verbena. In the far north, Tyrrell’s willow, an Arctic species, is restricted to the Athabasca Sand Dunes. Long-leaved bluets is found only in the sandhill sites north of Edmonton. Like most of the rare sandhill plants, it requires periodic sand disturbance to thrive; perhaps because of its small stature, it gets crowded out by tall, dense vegetation.

Like plants, insects have their various preferences for loose, open sand versus consolidated vegetation. Indeed, the fortunes of many species may depend upon a balance of environmental factors such as fire, drought, and climate warming that alter vegetation cover in the dunes.

Further Exploration

Alberta’s sandhills are worth exploring and protecting. They are the legacy of the last glaciation: infertile soils and varied topography that spur nature’s adaptability and diversity, a boon for the natural environment. Sandhill communities are also dynamic; no futures are assured in a changing climate or with changing land use.

Selected Sandhill Locations of Alberta North

Athabasca Dunes Ecological Reserve (and Maybelle River Wildland Park)

Richardson Wildland Provincial Park

Fort Assiniboine Sandhills Wildland Provincial Park

Holmes Crossing Sandhills Ecological Reserve

Various Natural Areas, e.g.: Bellis Lake, Bellis North, Bridge Lake, Clyde Fen, Halfmoon Lake, Nestow, Northwest of Bruderheim, Opal, Redwater

Edmonton Region: Bunchberry Meadows Conservation Area, Clifford E. Lee Nature Sanctuary, University of Alberta Botanic Garden

Central Parkland

Dillberry Lake Provincial Park

Wainwright Dunes Ecological Reserve (including David Lake)

South – Mixed Grassland

Middle Sandhills including Prairie Coulees Natural Area

Pakowki Lake

For more information contact Stewards of Alberta’s Protected Areas Association at sapaastewards.com.

Patsy Cotterill is a retired botanist who lives in Edmonton. She is a board member of the non-profit Stewards of Alberta’s Protected Areas Association and a keen advocate for Alberta’s natural environment.

Read the Original Article for this Post

For a richer reading experience, view this article in the professionally designed online magazine with all images and graphs in place.

This article originally ran in the Spring 2024 issue of Nature Alberta Magazine (Vol. 54 | No. 1).