The Amazing Migration of Neotropical Birds

22 April 2024

BY JIM BUTLER

Bird migration is among the most amazing natural phenomena on the North American continent, and the neotropical migrants are the most impressive. Bird migrants from Canada and the U.S. are divided into two groups: the Nearctic and the neotropical. The Nearctic group winters in the warmer parts of the U.S., particularly southern Florida and southern Texas. The neotropical migrants spend the winter in Central and South America, especially the Central American rainforest region, the drainage of the Orinoco River in Venezuela, the extensive Amazon rainforest, and the foothills of the Andes in Ecuador and Peru.

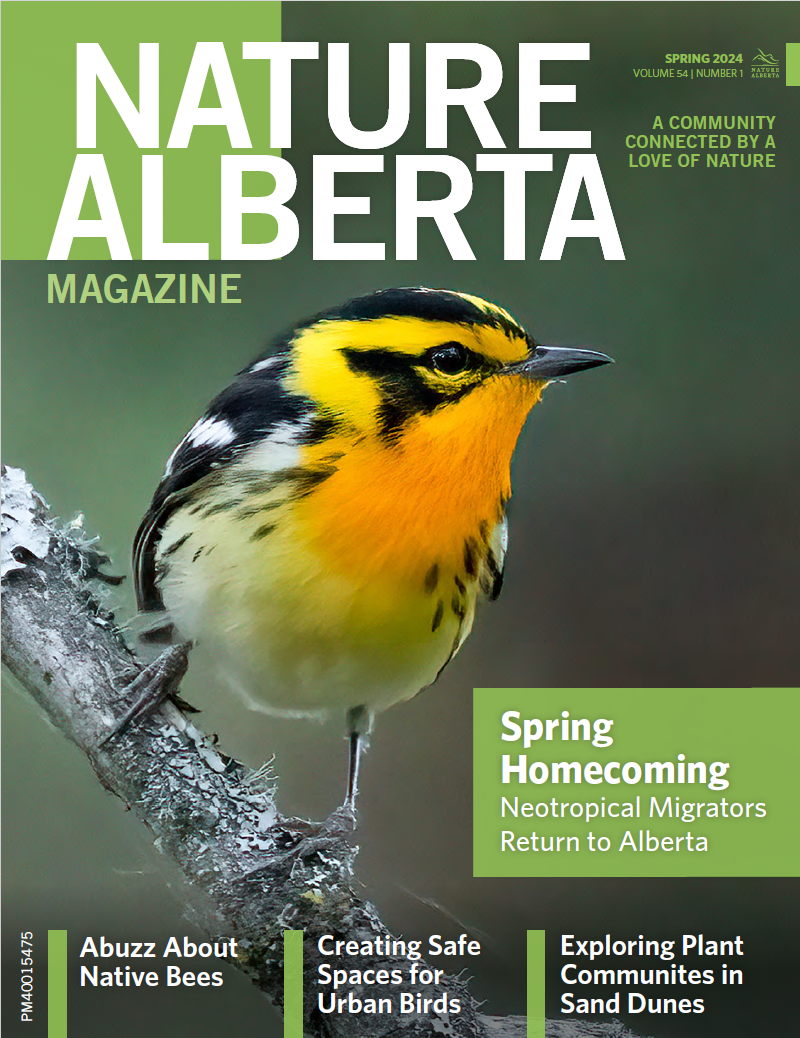

An important South American winter birding location for me has been in the Amazon forest of Ecuador, where I have seen many familiar bird friends from Canada, including several warblers (blackburnian, blackpoll, bay-breasted, and Canada) as well as redstarts and western tanagers. Another of my favorite birding destinations in the neotropics is the Calakmul Biosphere Reserve in the Yucatan Peninsula, home to 385 species of birds and 400 species of butterflies. It is one of Mexico’s largest protected areas, where one meets a variety of resident birds, such as the eastern thicket tinamou, blue-diademed motmot, and black-headed trogon, perched alongside our northern bird visitors.

My favorite group of neotropical migrants is the wood warblers. Many people consider these colorful warblers “candy for the eyes.” They are mostly arboreal insect gleaners with a preference for woodland forests, often in the highest canopies of the tallest trees. Migratory warblers from North America differ from the resident non-migratory warblers of the tropics in several ways. Compared with resident warblers, migratory warblers have shorter breeding cycles, have shorter lifespans, and lay larger clutches of eggs (four to seven). They also show marked differences between the sexes and take a different mate each year. And of course, they undertake long-distance migrations.

Adaptations for Migration

Before departing the southern hemisphere, migrating birds prepare for their journey north by doubling their body mass through increased feeding, called hyperphagia. Stored fat provides 90% of the energy utilized by birds during long-distance flight, with the remainder from protein and a bit from stored carbohydrates. High-fat fruits and seeds provide all the essential fatty acids the birds need.

Much has been learned about bird migration over the years. Over land, they typically fly for half the night, travelling 150 to 300 km. They orient themselves using stars and the Earth’s magnetic field. One of the most interesting findings is that birds can sleep in flight, perhaps with one eye open for predators, in the manner of dolphins and whales. This fascinating phenomenon is called unihemispheric sleep. It is short and fragmentary, yet sometimes whole, with both brain hemispheres asleep in flight. Despite being asleep, the birds are still able to sustain aerodynamic control. (Something I suspected a segment of my students demonstrated during my lengthy, low-light slide lectures.)

Researchers have proven that monitored frigatebirds sleep for periods during their long, gliding flights, which last for days. Old World alpine swifts, known for their rapid wing beats, have also been proven to sleep when aloft for days, using their unihemispheric capability. Research on sleep has not yet been applied to our North American wood warblers. Some research in England has referenced warblers, but these are from an unrelated family of warblers represented in North America by kinglets and gnatcatchers, all of which are moderate migrators, never travelling farther than Guatemala. I suspect that North American wood warblers might well have unihemispheric capabilities as well, which would explain much in the redoubtable ways of this accomplished group.

The Journey Begins

In late March, more than 150 species of North American birds suddenly and silently alight, up and out of the South American jungles, forests, and savannahs, as if summoned by sirens. Five billion birds launch into the air, seemingly on the same evening. How these birds manage to take flight nearly simultaneously, well out of each other’s view, is an intriguing mystery. In the neotropical jungles, the resident birds, such as toucans, parrots, and motmots, must be relieved that tourist season is over and the treetops are quieter. Perhaps only the stealthy arboreal snakes that have been feeding upon the migrants are sad to see them go.

Migrating songbirds typically fly solo at first, but eventually they find themselves travelling and foraging in mixed flocks to improve foraging efficiency and provide greater security in detecting hawk predators who are also migrating. For example, Harris’s hawks organize in groups to prey upon the growing numbers of gathering songbirds. Small songbirds, such as warblers, share the mixed cloud groups with a range of larger birds, but as the migration continues toward their nesting areas, the bird species increasingly cluster around their own kind.

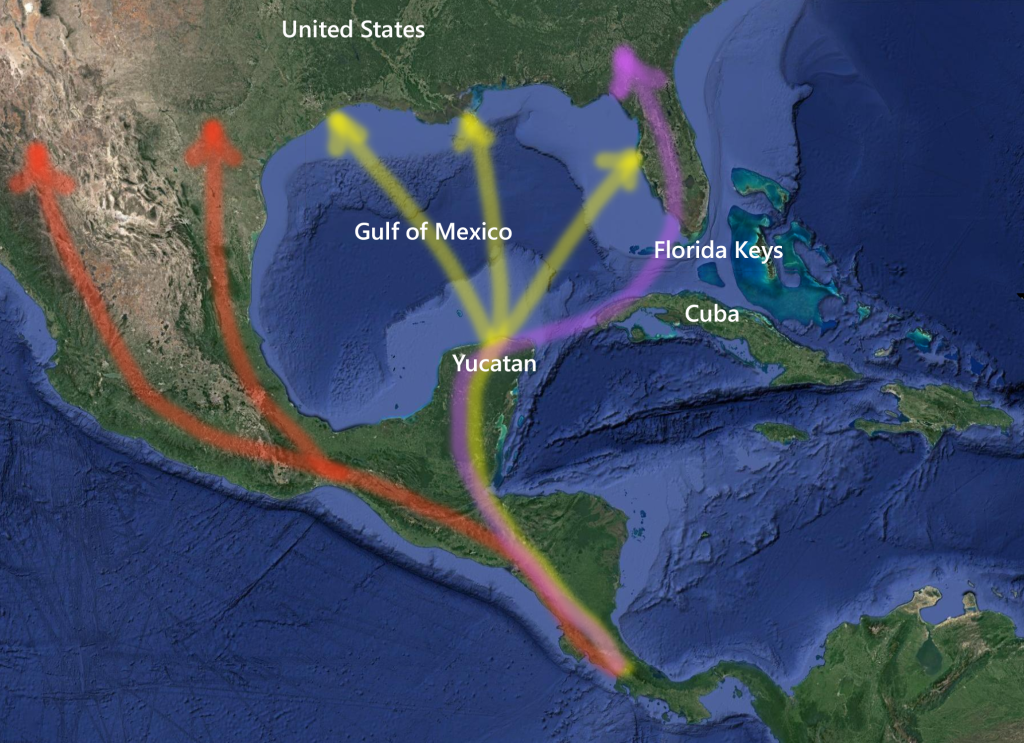

Neotropical migrants initially travel northward through Central America into Mexico. There they face a decision: keep flying mostly over land or take the shorter route across the Gulf of Mexico — the largest island-free gulf of water in the world. Many birds choose the presumably safer land route, even though it adds hundreds of kilometres to their trip. Some continue straight north through Mexico and into the western U.S. (see map). Others head east from Mexico’s Yucatan Peninsula to Cuba, a 300-km journey across water. From there it is only a short hop to the Florida Keys, where they are joined by migrants from the West Indies.

Returning neotropical migrants travel north through Central America, and after reaching Mexico they take one of several routes into the U.S. The water crossing over the Gulf of Mexico is the shortest, most popular route.

Despite the hazards, most neotropical migrants choose to cross the Gulf of Mexico. The primary staging area for this crossing is the Yucatan Peninsula, which juts northward into the Gulf and serves as a launching platform 300 km closer to the other side. Billions of birds make the crossing, making it the largest open-water crossing of land birds in the world, confirmed by radar readings. More than 30 species of wood warblers cross the Gulf each year, along with sandpipers, orioles, grosbeaks, indigo buntings, and many other species.

Crossing the Gulf of Mexico entails a 1,000-km non-stop journey. The birds wait up in the treetops till dark and finally, as nightfall approaches, they embark. The birds fly beneath the stars in loose groups, at about 50 km/h and at an altitude ranging from 300 to 1,500 m. The crossing can be as short as 12 hours with a good tailwind or a frightening 30 hours in a strong headwind. Fortunately, winds customarily blow northeast, aiding the migrants. But foul weather can be deadly, evidenced by drowned birds washed up on the U.S. shore. For those that make it, the U.S. shoreline and forest welcome the migratory birds and provide a welcome opportunity to rest and feed.

On to Canada

I enjoy attending the spring Featherfest in Galveston, Texas to view shorebirds en route to the Canadian far north. Most of these shorebirds use the Atlantic Flyway on their northward journey, making a pit stop along the shores of Delaware Bay, Maryland. Every year, hundreds of thousands of horseshoe crabs converge on the shores of Delaware Bay and Chesapeake Bay to breed and lay their eggs in the sand. The crabs spawn many times throughout May and early June, and it is estimated that each female lays around 88,000 eggs every year, depositing up to 4,000 eggs in each nest. During this time, shorebirds wisely lay over in Delaware Bay to feast on the freely available crab eggs. Some have been known to eat so much that they were almost too heavy to be able to take off. Many of these shorebirds will never be seen here in Alberta. Fully refueled, they will head directly for the northern Arctic with limited pauses.

Once in the U.S., Canadian songbirds require roughly 14 days before they reach the Canadian border, typically in the Great Lakes Region, where they divide into western-bound and eastern-bound groups. Along the way they are greeted by birdwatchers in the thousands. Many migrating songbirds build up in large numbers along the southern shore of Lake Erie, waiting for the proper weather and favorable winds for crossing the lake, which is both large and known for frequent dangerous storms. A key destination is Point Pelee National Park, which is on a long peninsula that extends southward from the north shore of Lake Erie (it’s the southernmost point of land in Canada). Although the Lake Erie crossing is much shorter than the Gulf crossing, it can still be treacherous. Under pressure to reach their breeding territories, the birds are sometimes tempted to embark at the wrong time, right into one of these storms. Some major fallouts have been observed in the park when birds have flown through storms and fog to reach the north shore, cold and exhausted.

Songbirds reach Alberta throughout May. By June, they have dispersed throughout the province to their individual nesting territories and are busy singing, mating, and eventually rearing young. Most songbirds seem to exhibit breeding site fidelity. An example is the familiar purple martin, a neotropical migrating bird that winters in large flocks in the jungle of southern Brazil and northern Argentina. These birds return to the same purple martin “hotels” year after year. Many other northern songbirds do the same, establishing their territory within yards of previous nesting sites.

My home in Edmonton is a notable annual migration layover, serving as a bird-friendly, forested space with flowing water. My yard list exceeds 100 species and I often recognize the manners of familiar return visitors. It’s humbling to know that these birds have survived aerial predators, storms, drowning, and exhaustion. And then there are the human-based hazards on land, like windmill towers, electric towers, and windows in homes and skyscrapers. I hope you can enjoy these delights this spring in your own backyard and nearby green spaces. We should all do what we can to aid their journey and to support their conservation.

Jim Butler is a Professor Emeritus of Forest Ecology and Wildlife from the University of Alberta. Founder of the Conservation Biology program, he is a highly respected naturalist and scientist worldwide.

Read the Original Article for this Post

For a richer reading experience, view this article in the professionally designed online magazine with all images and graphs in place.

This article originally ran in the Spring 2024 issue of Nature Alberta Magazine (Vol. 54 | No. 1).