The Recovery of Trumpeter Swans in Alberta

BY NICK CARTER

The musical, horn-like call of the trumpeter swan is a beautiful feature of Alberta’s wilderness. There was, however, a time when the trumpeter swan had very nearly disappeared from our wetlands and pastures. What caused this magnificent bird’s decline, and what does its future as a species look like in our province?

Natural History

Trumpeter swans are massive birds, the largest native to North America, much larger than other waterfowl species. Leo de Groot.

The trumpeter swan is the largest and heaviest bird native to North America, measuring up to two metres from bill to tail and weighing an average of 11 kg. This is a massive bird — no other Alberta waterfowl species comes even close.

Adults are entirely white, with a long neck, black beak and face patch, and black legs. Juveniles are mostly pale grey in colour and sport a pink blotch on the top of the bill. They obtain their fresh crisp white adult plumage as they enter their second year.

Trumpeter swans can easily be confused with tundra swans, which also occur in Alberta. Tundra swans are also pure white with black bills, but they are only about half the size of trumpeter swans. A small yellow patch in front of the eye is another distinguishing feature. In addition, tundra swans nest in the Arctic, so they are generally only seen during migration, whereas trumpeter swans can be seen in Alberta all summer long.

A distinguishing feature of the tundra swan, shown here, is a yellow patch on the beak just below the eye. The bill of a trumpeter swan is all black. Tony LePrieur.

Trumpeter swans winter in the northern United States and return to Alberta in early April. Returning flocks feed on prairie croplands as they move north and then break off into pairs to nest in small wetlands across the Parkland, Boreal, and Foothills regions. They build their nests with aquatic vegetation, often on top of a muskrat den or beaver lodge, and monogamous pairs often return to the same nest site year after year. Four to six off-white eggs are laid in early May and the fuzzy grey cygnets hatch about a month later. Cygnets spend the summer with their parents before being driven off to fend for themselves at the end of the year.

During the summer, trumpeter swans feed mainly on aquatic plants found in shallow, quiet ponds, marshes, and small lakes. They forage either by skimming the surface of the water like a dabbling duck or by using their long necks to reach the muddy bottom and prying food items up by the roots. They also paddle their feet in place to stir up water currents to dislodge firmly rooted plants. Smaller waterfowl, like dabbling ducks, will take advantage of this behaviour, following in the wake of foraging swans and feeding on the vegetation they stir up. On the wintering grounds, their diet is mostly tubers and waste grain from agricultural crops.

Swans congregate in flocks on and around large water bodies during the fall in preparation for migration. Late bloomers are sometimes left behind. I once observed a lone juvenile trumpeter being harassed by a fox just outside of Wembley in late November, about a month after all other swans had left.

Alberta is an important region for trumpeter swans, and within the province there are several well-established breeding locations. The heart of their Alberta range is in the Peace Country, most notably in an area immediately north and west of Grande Prairie. This region is designated as an Important Bird Area, and trumpeter swans have been observed nesting in at least 28 lakes here. A well-known pair has occupied Crystal Lake in a suburb of Grande Prairie on a regular basis. The trumpeter swan has fondly become the official symbol of Grande Prairie, which is often referred to as the “Swan City.”

During the summer, trumpeter swans are usually found in shallow, quiet ponds, marshes, and small lakes where they feed on aquatic plants. Nick Carter.

Additional nesting areas are scattered throughout northwestern Alberta, the southwest corner of the province around Pincher Creek, Elk Island National Park, and the foothills from Edson to Whitecourt. Look for them on reedy ponds and lakes, grazing in pastures, or flying overhead in these areas.

Population Decline and Conservation Efforts

Historically, trumpeter swans were found throughout Alberta. But by the early 1900s, the species was near extinction, mainly because of overhunting.1 The bird’s white plumage was a popular fashion accessory and collector’s item. Swans were also hunted for their meat, skins, and quills, which were used as writing pens. In later years, the drainage of wetlands for agriculture deprived the swans of important nesting habitat. By the early 20th century, the species was reduced to a few remnant populations scattered across North America, including one in the Grande Prairie region.

Early government protection measures and local efforts were instrumental in saving the trumpeter swan from extinction. The 1917 Migratory Birds Convention Act made it illegal to hunt trumpeter swans in Canada and the United States followed suit the following year. More locally, Saskatoon Island Provincial Park was established in 1932 just west of Grande Prairie as a critical refuge for swans and other migratory birds. This site was later designated as a federal migratory bird sanctuary. Another important step was the translocation of trumpeter swans from the Grande Prairie area to Elk Island National Park in 1987, re-establishing a breeding population in the Central Parkland region. To support management efforts, formal surveys of swan populations began in the Grande Prairie area in 1953 and were extended to all of Alberta in 1985.2

More recently, the provincial government developed two comprehensive five-year recovery plans, released in 2006 and in 2013.2 The stated recovery goals of the 2013 plan were to maintain or increase the breeding population of trumpeter swans in already occupied regions and to expand the breeding range of the species into regions it had historically occupied, including the establishment of ten breeding pairs in the Beaver Hills. There have been no further updates to the recovery plan since 2013.

The recovery plans recognized that, even though hunting has been curtailed, trumpeter swans still face a variety of threats. Swans are sensitive to human disturbances, such as removal of shoreline vegetation, boating, swimming, and other forms of development and recreation in wetlands. Fluctuating water levels can drown nests during floods or cause habitat loss during droughts. Trumpeters also avoid sensory disturbances, such as nearby traffic and similar intrusions, and will abandon their breeding sites if they feel disturbed. Power lines are another hazard, causing injuries and death.

In terms of conservation actions, the 2013 recovery plan focused on preventing the loss of critical breeding and staging habitat through cooperation between government, industry, and private landowners. Additional steps included information and outreach efforts, research and monitoring of swan populations, developing partnerships among government and non-government agencies, and subsequent assessment of trumpeter swan conservation efforts.

A Conservation Success Story

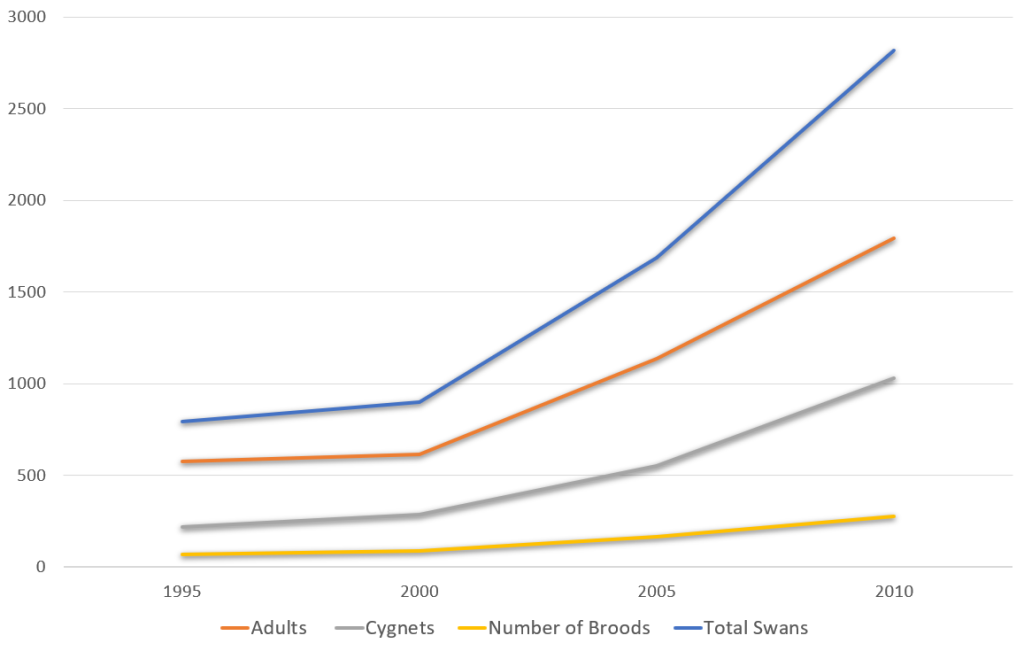

By 1995, Alberta’s trumpeter swan population had increased to 792 individuals, with 67% of the total found in the Grande Prairie-Valleyview area.2 Because of this positive trend, trumpeter swans were upgraded from “Endangered” to “Threatened” in 1997. With continued population growth, the species was further upgraded to “At Risk” in 2000.3

By 2010, Alberta’s trumpeter swan population had increased to 2,821 individuals.2 The Grande Prairie-Valleyview area was still home to most swans, accounting for 61% of the total (1,717 individuals). The second-highest population was further north, between Peace River and Peerless Lake (863 individuals). And the Beaver Hills population, centred on Elk Island National Park, numbered 54 individuals (up from 11 in 1995).

Trumpeter swan population size by type, 1995–2010. A follow-up survey in 2015 found that the total population was 7,734. Data source: Alberta Environment and Sustainable Resource Development.

A survey in 2015 showed even better results, with 7,734 individuals counted according to Provincial Wildlife Specialist Mark Heckbert, who leads the trumpeter swan recovery effort in Alberta. As a result, the species status in Alberta was upgraded to “Sensitive,” where it remains today.3 The Alberta government still considers the trumpeter swan to be a species of special concern, but because of the excellent population growth seen in the 2015 survey, it did not conduct a follow-up survey in 2020.

Given this impressive population growth, trumpeter swan recovery in Alberta can be considered a resounding success. But certain regions have seen better population growth than others, so there are still areas for improvement. For example, the Waterton-Pincher Creek region showed no growth from 1995 to 2010, and Lac La Biche went from nine individuals in 2000 to zero in 2010.2

Though the trumpeter swan is not fully secure in Alberta, the prospects for continued population growth and breeding range expansion are good. According to Heckbert, factors leading to continued recovery of trumpeter swans include better water quality in wetlands that are free from disturbance, as well as improvement in winter feeding conditions in the United States. Well-fed swans returning to Alberta in the spring are continuing to produce high numbers of cygnets.

Outside of northwestern Alberta, however, challenges persist. Trumpeter swans continue to breed in the Pincher Creek area, but the limited amount of suitable habitat is preventing population increase in the region. Moreover, while the reintroduction program to Elk Island National Park helped establish trumpeter swans east of Edmonton, they have not become as numerous in the general area as had been expected, and the goal of establishing ten breeding pairs in the surrounding Beaver Hills has not yet been realized. This, according to Heckbert, is puzzling, as the region should provide excellent trumpeter swan breeding habitat. The species has also failed to gain a footing in northeastern Alberta, possibly because of the colder and deeper lakes there.

Trumpeter swans remain sensitive to human disturbances from both industrial and individual activities, so now is not the time for us to ease up on protective measures. There are many ways that members of the public can help trumpeter swans in their recovery. The swans do best in the absence of human activity. We should give them space when we are in their habitat, avoid approaching approach them on foot or boat, instead admiring them from a distance while leaving their wetland homes unpolluted. Be a respectful neighbour and refrain from loud, high-energy activities like power boating or shooting near swan breeding areas. Hunters should know their targets well and not mistake protected swans for geese or other waterfowl. Lastly, supporting causes and campaigns aimed at protecting wetlands from development and destruction will ensure that swans will always have a summer home in Alberta.

Trumpeter swans remain sensitive to human disturbances from both industrial and individual activities, so now is not the time for us to ease up on protective measures. There are many ways that members of the public can help trumpeter swans in their recovery. The swans do best in the absence of human activity. We should give them space when we are in their habitat, avoid approaching approach them on foot or boat, instead admiring them from a distance while leaving their wetland homes unpolluted. Be a respectful neighbour and refrain from loud, high-energy activities like power boating or shooting near swan breeding areas. Hunters should know their targets well and not mistake protected swans for geese or other waterfowl. Lastly, supporting causes and campaigns aimed at protecting wetlands from development and destruction will ensure that swans will always have a summer home in Alberta.

References:

- Alberta Environment and Sustainable Resource Development and Alberta Conservation Association (2013). Status of the Trumpeter Swan (Cygnus buccinator) in Alberta: Update 2013. Alberta Environment and Sustainable Resource Development. Alberta Wildlife Status Report No. 26 (Update 2013).

- Alberta Environment and Sustainable Resource Development (2013). Alberta Trumpeter Swan Recovery Plan 2012– Alberta Environment and Sustainable Resource Development, Alberta Species at Risk Recovery Plan No. 29.

- Alberta Environment and Parks https://extranet.gov.ab.ca/env/wild-species-status/default.aspx

Nick Carter is a writer, photographer, and naturalist from Edmonton. From birds and bugs to flowers and fossils, Nick is always seeking out the natural wonders of this province and sharing his enthusiasm with others.

This article originally ran in Nature Alberta Magazine - Winter 2023.