Citizen Scientists Come to the Aid of the Tenacious Franklin’s Ground Squirrel

Richardson’s ground squirrels are mostly tan in colour with a darker back. They lack the gray head and tail that distinguishes Franklin’s ground squirrels. Elron.

BY GILLIAN CHOW-FRASER AND RICHARD SCHNEIDER

Did you know Alberta is home to five ground squirrel species? Ground squirrel roll call! In the prairies and parkland we have the ubiquitous Richardson’s ground squirrel and the less common thirteen-lined ground squirrel. The Rocky Mountains and foothills are home to the Columbian ground squirrel and the uniquely marked golden-mantled ground squirrel. And finally, there is Franklin’s ground squirrel — lesser known, but nevertheless an important member of the parkland ecosystems of central Alberta.

“Bush Gopher” Background

The Franklin’s ground squirrel has the typical shape of a ground squirrel but differs from its cousins in several ways (see the accompanying photographs). Its most distinctive feature is a long, bushy tail, which is about is about a third of its overall length. Its head and tail are gray and its back has a reddish colour, to a variable degree. Its underside is yellowish white. Franklin’s ground squirrels are a bit larger than the more common Richardson’s ground squirrel. It can also be differentiated by its habitat preferences.1 Rather than favouring open prairie, it is usually found in semi-open shrublands and aspen forest, which is how it earned its moniker of “bush gopher.” These squirrels are often seen along forested grassland edges and the tall grasses bordering croplands or marshlands.

Red squirrels are easily distinguished from Franklin’s ground squirrels by the long, bushy tail and pointed ears. Tony LePrieur.

Franklin’s ground squirrels are surprisingly tenacious. They feed mostly on vegetation, but also eat insects, small mammals, frogs, birds, and bird eggs. Small as it is, this rodent has even been known to kill prey the size of chickens and ducks! They are the only ground squirrels known to also climb trees, and are skilled enough to pillage songbird nests. Surprisingly vicious for such cuddly-looking critters!

Living in small, loosely knit colonies, Franklin’s ground squirrels are the least social of the ground squirrels. Their prairie cousins are more aggressive, but fighting does occur, especially during mating season. They have been described as one of the more vocal ground squirrels. When interacting with other squirrels, they can growl or unleash was has been described as a “bubbly trill” or musical whistles.

Franklin’s ground squirrels escape harsh winters by hibernating underground in extensive tunnel systems. Adult males emerge from hibernation first, in early April to mid-May. Females emerge later. After mating, females bear their litters in underground dens. Litter sizes average about seven to nine pups but can vary from two to 13. Adults first retreat underground in mid-August or September for hibernation, while young-of-the-year pups spend another six weeks above ground to continue to fatten up in preparation for six to eight months of underground hibernation.

Franklin’s ground squirrels have a gray head, a gray bushy tail, and reddish fur on the back. David Scott.

Conservation Concerns

Franklin’s ground squirrels are found across the prairie provinces and in Ontario.1 They are considered “Secure” in Saskatchewan and Manitoba but have been designated as “Imperiled” in Ontario. In the United States, Franklin’s ground squirrels have declined throughout their eastern range and are listed as a species at risk in several jurisdictions.2 In all parts of their range, habitat fragmentation and loss from agricultural expansion along with pest control have been the main causes of the squirrel’s decline.

In Alberta, the status of Franklin’s ground squirrel has still not been determined. The provincial government maintains that there is not enough information to say whether the population is stable or imperiled. Talk to experienced naturalists, though, and you will hear stories of serious concern about the fate of this squirrel. For example, individuals who used to see them regularly in the Clifford E. Lee Nature Sanctuary near Edmonton have noted their absence in recent years. Though such observations are anecdotal, they provide a compelling reason for concern and conservation action.

Leaving the squirrels in “data limbo” is dangerous. Since it has no official status as a species of concern, no conservation action is taken. This means the monitoring needed to determine the squirrel’s status is not being done either. It’s a catch-22. In the meantime, squirrel populations may be declining year by year.

Citizen Scientists Fill the Gap

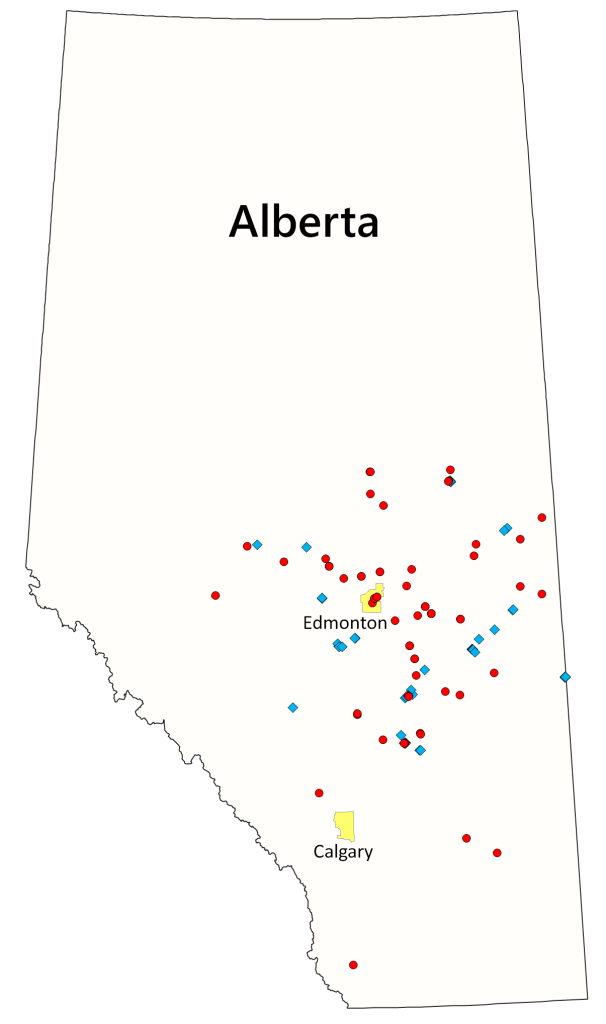

Sightings of Franklin’s ground squirrels across Alberta (see text for sources). Blue diamonds correspond to observations made over the past decade, and red circles correspond to older observations. At this resolution some data points overlap, so not all 136 observations are visible.

In the spring of 2022, Nature Alberta initiated a citizen science project to help fill some of the data gaps with respect to Franklin’s grounds squirrels in Alberta. Citizen science projects use volunteers to gather data on wildlife and ecological processes. Many citizen science programs have run for decades and have a proven track record of contributing to biodiversity conservation. With the advent of citizen science apps for smartphones, the number of participants has skyrocketed in recent years. Having many “eyes on the ground” makes citizen science especially useful for collecting observations of rare and endangered species, which are difficult to monitor with conventional research programs.

Nature Alberta’s citizen science project had two components. First, we created a Franklin’s ground squirrel project on iNaturalist and asked the Alberta naturalist community and the general public to participate (inaturalist.ca/projects/franklin-s-ground-squirrels). iNaturalist is the world’s largest citizen science platform devoted to general biodiversity. Worldwide, there are now more than two million iNaturalist users who have collectively contributed close to 100 million observations. Behind the scenes, a community of volunteer naturalists works to help identify the species submitted to the database. All of the information gathered is made available to the public at no charge through the iNaturalist website, which can be searched by species, location, date, or by specific project.

To help participants know what to look for, Nature Alberta provided identification tips and photographs of Franklin’s ground squirrels on its website (naturealberta.ca/ground-squirrel). Once in the field, participants were asked to take a photo of any Franklin’s ground squirrels they encountered using the iNaturalist app. The app automatically adds the time and GPS location of the observation and submits everything to the iNaturalist database. Once submitted, the identity of the species is verified by the online naturalist community.

The second component of Nature Alberta’s project was to ask the naturalist community to submit information on past sightings. Participants submitted these past observations through a form on our website. Lastly, we requested a download of Franklin’s ground squirrel observations from the government’s Fisheries and Wildlife Management Information System (FWMIS). The FWMIS database is a repository of fish and wildlife observations submitted to the government by various organizations (though not including iNaturalist).

By the fall of 2022, we had 136 observations to work with: 43 from iNaturalist, 14 sent by naturalists via the website, and 79 from the FWMIS database. The majority of the FWMIS observations (56 of 79) were labelled as legacy data, from museum collecting in the 20th century. The data we assembled could not be used to assess changes in population size over time because the amount of effort varied considerably from year to year. However, it was possible to draw insights about the squirrel’s spatial distribution.

We can confirm that the range of Franklin’s ground squirrels in Alberta is centered on the Central Parkland and adjacent Dry Mixedwood natural regions (see map). Based on this pattern, one would expect to find the squirrels in the Peace Country as well, especially around Grande Prairie, but there were no sightings in this area. This may indicate range contraction, though without better historical data there is no way to be sure. One would also expect to find the squirrels along the Eastern Slopes, where the foothills transition to prairie. Indeed, there were two historical sightings here, but none in the last decade. So again, this may indicate range contraction, but we cannot be sure.

If you see a Franklin’s ground squirrel, be sure to take a photo and submit it to iNaturalist. Matt Reinbold.

Another noteworthy finding is that, historically, the Edmonton region and lands north of Edmonton formed the heart of the squirrel’s range (see map). However, over the past 10 years, there were no sightings at all in this region. The fact that there were many iNaturalist sightings further west, south, and east of Edmonton suggests that there has been a localized decline in the squirrel population in the Edmonton region rather than a lack of observer effort.

Lastly, a large proportion of the observations made in the last decade occurred within parks and protected areas. This could, in part, be because iNaturalist users tend to visit parks on their outings. However, it seems unlikely that this pattern is simply coincidence. Instead, it’s likely that the squirrels, like people, prefer to hang out in areas that are relatively intact (rather than in canola fields).

Next Steps

Though uncertainties about the Franklin’s ground squirrel remain, there is sufficient evidence of range contraction to place the squirrel in the category of “Sensitive.” This would motivate further study, including systematic surveys to assess population trends. Moreover, it would provide baseline protection for the squirrels. For example, in 2017, a research study on duck predation led to the killing of nine squirrels near Buffalo Lake, whereas badgers were excluded from trapping due to their status as a “Sensitive” species.3 Protection from pest control is also needed.

More generally, funding for species at risk research and management needs to be restored. Alberta’s strategy for the management of species at risk was written in 2008 and expired eight years ago.4 It has never been updated. Progressive funding cuts have seriously diminished what government biologists can accomplish, even as the threats facing our species at risk continue to increase. This is completely at odds with public values and expectations.

We thank everyone who contributed to the Franklin’s ground squirrel citizen science project so far. As this project demonstrates, citizen science observations can make a meaningful contribution to conservation of sensitive species. It’s a great way for anyone who cares about nature to make a difference. Our plan is to keep the project running to further improve our understanding of this squirrel. So please keep the observations coming — visit naturealberta.ca/citizen-science for more information. We will also keep advocating for the squirrel’s protection.

Fortunately, Franklin’s ground squirrel is not at immediate risk of disappearing from Alberta. It’s more a matter of halting further range contraction and long-term population decline. With appropriate proactive management it should be possible to ensure that these tenacious squirrels remain with us indefinitely.

References

- J. Huebschman (2007). Distribution, Abundance, and Habitat Associations of Franklin’s Ground Squirrel. Illinois Natural History Survey Bulletin, Vol. 38, Article 1.

- J. Martin et al. (2003). Franklin's Ground Squirrel (Spermophilus franklinii) in Illinois: A Declining Prairie Mammal? The American Midland Naturalist, Vol. 150, No. 1.

- Blythe, E. and M. Boyce (2020). Trappings of Success: Predator Removal for Duck Nest Survival in Alberta Parklands. Diversity, Vol. 12.

- Alberta Fish and Wildlife Division (2008). Alberta’s Strategy for the Management of Species at Risk (2009-2014). Government of Alberta, Edmonton, AB.

Gillian Chow-Fraser is the Boreal Program Manager at the Canadian Parks and Wilderness Society (CPAWS) Northern Alberta, where she leads on conservation work in the boreal forests of Alberta to protect their wilderness and the wildlife that depend on it.

Richard Schneider is a conservation biologist who has worked on species at risk and land management in Alberta for the past 30 years. He currently serves as the Executive Director of Nature Alberta.

This article originally ran in Nature Alberta Magazine - Winter 2023.