What Happened to the Northern Leopard Frog?

BY LAURA SOUTHWELL

The northern leopard frog is an iconic amphibian, likely the very image that comes to mind when you hear the word “frog.” This once ubiquitous resident of prairie wetlands has faced an ongoing struggle against a changing and increasingly human-centric environment. Its abundance in Western Canada has been greatly reduced since the 1970s, and the remaining populations are fragmented and widely scattered.1 It is now classified as threatened in Alberta. Fortunately, these amphibians are still thriving in Eastern Canada and the U.S., yet it is troubling that a species can go from being successful to threatened in the space of a few decades.

Several species of leopard frog exist in North America; however, the only species found in Alberta is the northern leopard frog. Its greenish-brown colouration (varying among individuals from bright green to dark olive brown), namesake dark spots, and white underbelly make it easy to distinguish from Alberta’s other frog species (wood frog, boreal chorus frog, and Columbia spotted frog, as well as several toads).

Leopard frogs are easy to identify because of their dark spots and white bellies. Their skin color is variable, ranging from bright green to dark olive. ANDREW DUBOIS

The northern leopard frog is a medium-sized frog that can grow up to 13 cm in length. Far from being simple pond dwellers, these frogs also inhabit marshy areas and moist grasslands. They generally prefer shallow, still, or slow-moving water for breeding and deeper permanent water bodies that do not completely freeze for overwintering.

Adult northern leopard frogs, like many amphibians, will venture out from ponds to hunt. They are mainly sit-and-wait predators that ambush anything that fits in their mouths. They eat a wide range of invertebrates, small mammals, reptiles, and other amphibians, including their own species. Aquatic larval frogs, or tadpoles, are herbivorous and consume easily accessible aquatic plant matter like algae.

Leopard frogs themselves fall prey to many species including fish, heron, snakes, otters, foxes, as well as other frogs, during all stages of life. They must rely on evasion and their cryptic colouration to avoid predation.

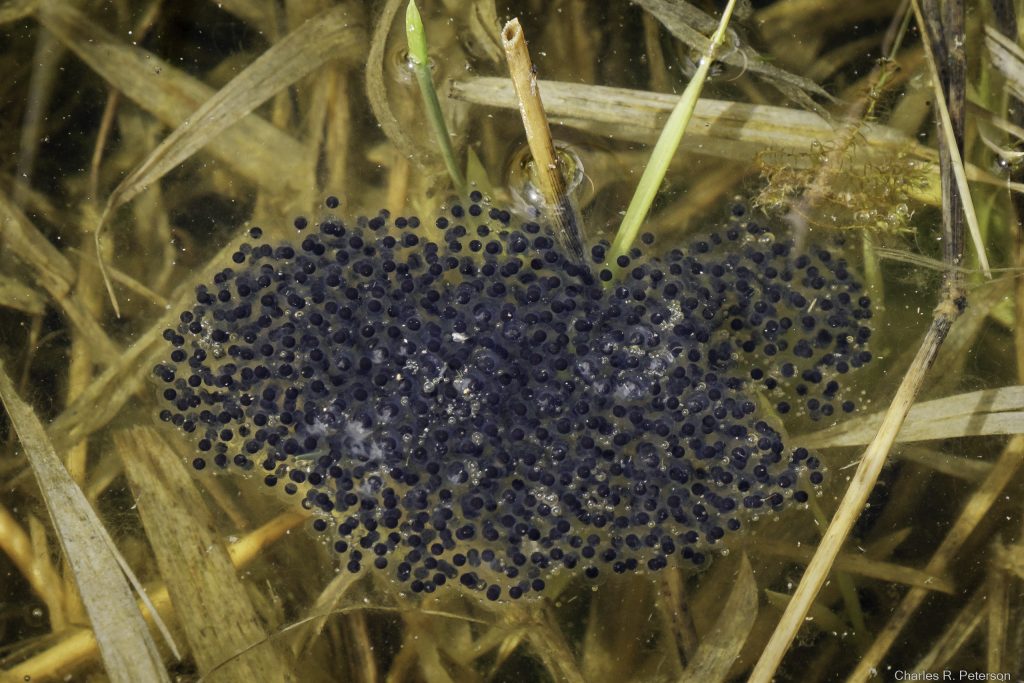

Leopard frogs lay up to a thousand eggs at a time. CHARLES PETERSON

In late spring, largely depending on temperature and ice conditions, sexually mature adult frogs congregate in still or slow-moving bodies of water to breed. The northern leopard frog has a distinctive, rumbly, snore-like call used for attracting potential mates. During mating, the male grasps the female and sits on her back until she lays her eggs. He fertilizes the eggs as they are laid and may then leave to find other mates. Typical egg masses contain up to a thousand eggs and are often laid close to other egg deposits.

Young leopard frogs are initially aquatic tadpoles. They lose their tail and grow legs as they mature into adults. HELEN LITTLETHORPE

After about two weeks, the eggs hatch into tadpoles. At this stage they are at their most vulnerable and are often subject to predation by fish, water beetles, large invertebrates, and other frogs. Over the course of several months, tadpoles metamorphose, losing their tail and growing limbs as they transition to their adult terrestrial lifestyle. Young frogs forage and continue developing for between two to three years before becoming sexually mature.

Causes of Decline

Ecologists believe that the decline in northern leopard frogs is the result of several factors working in combination. The main threats fall into three categories: habitat deterioration, chemical pollutants, and diseases.

Leopard frog habitat includes wetlands (for larval growth, breeding, and overwintering) and adjacent upland areas (for foraging). Not only must these habitats must be present, the frogs also need to be able to move freely between them. Human activities such as farming, wetland drainage, and roadbuilding have reduced the amount of habitat available to the frogs and restricted their movement.2 These activities have also reduced the quality of the remaining habitat and caused habitat fragmentation. Cumulative habitat changes have had a significant negative effect on leopard frog survival and reproduction.

Another significant threat to the northern leopard frog is chemical contamination. Amphibians in general are very vulnerable to harm from pesticides, herbicides, and industrial chemical wastes because their skin is permeable and because these chemicals accumulate in the wetlands where they live. In high concentrations, exposure can have a direct impact on tadpoles and frogs. But perhaps even more significantly, these chemicals can harm the aquatic invertebrates that the frogs eat, leading to reduced food intake and ultimately lower reproduction.

The decline in northern leopard frog populations has also been linked to disease. The main culprit is the chytrid fungus, which has been implicated in the mass die-off of many frog species around the world since the 1990s. This fungus has been identified in many Alberta wetlands and in numerous northern leopard frog populations. It infects the skin and inhibits the ability of frogs to breathe, hydrate, and regulate their temperature correctly. Other diseases identified in western populations of northern leopard frogs include ranavirus infection and “red-leg,” both of which can cause death in infected individuals.

Other threats to northern leopard frogs include being killed on roads and increased predation from the introduction of new predator species — particularly fish stocking in lakes. In addition, poorly managed livestock can cause erosion and habitat disruption in wetland areas from grazing and physical disturbance close to shorelines.

LORIE SHAULL

Conservation Efforts

Efforts to recover Alberta’s northern leopard frog population began with its listing as a threatened species by the Alberta government in 2004 and the development of a recovery plan in 2005. Conservation efforts have involved surveys to determine where the remaining frogs were located, conservation research, and outreach to local landowners to educate them about stewardship opportunities.

Recovery efforts have also included frog reintroductions.3 Alberta’s remaining frog populations are fragmented and widely separated, and this limits the potential for natural population expansion. To speed the recovery process, wildlife managers have been physically moving egg masses and tadpoles to suitable habitat within the frog’s former range. The eggs have been obtained from sites with stable frog populations.

Of course, reintroductions will not be successful without attention to the factors that caused the frogs to decline in the first place. The protection of frog habitat, including wetlands and surrounding upland areas, is paramount. The problem is that most of the northern leopard frog’s range coincides with Alberta’s agricultural zone. In this, the frog is in the same precarious position as many other threatened species in Alberta; this is a working landscape with little native habitat remaining and few options for large-scale protection. Conservation programs, such as Multiple Species at Risk (Multi-SAR) and Cows and Fish, do exist; however, they rely largely on voluntary stewardship efforts by landowners. Progress is being made, though not at the pace and scale needed to ensure the recovery of the many species at risk that rely on healthy prairie ecosystems.

There is not much that can be done about diseases directly, since medicating individual animals is not practical. However, as with most diseases, individuals that are in good condition and live in a healthy environment stand a much better chance of surviving infection. Therefore, conservation efforts that improve habitat quality and reduce chemical contamination serve as important preventative measures. In addition, natural selection often leads to genetic changes that improve resistance to serious pathogens.

No formal reports on the status of Alberta’s northern leopard frog have been published in the past decade. However, wildlife managers believe that populations within the core of their range are currently stable. Reintroduction efforts are generally on hold, with the notable exception of Waterton National Park, where an active reintroduction program is underway. The most recent recovery plan covered the period from 2010–2015 and no new version has been developed.2

How You Can Help

There are several things that you can do to support Alberta’s struggling leopard frogs. To begin, you can assist in population monitoring by participating in citizen science initiatives such as iNaturalist (inaturalist.ca). It couldn’t be easier: get the app, put on your hiking boots, and snap pictures of the species you encounter (especially leopard frogs). Your observations are verified and added to a publicly available database that’s easy to search and view on a map. These citizen science observations play an important role in uncovering new populations, complementing government monitoring efforts which are currently focused on periodically checking the status of known sites.

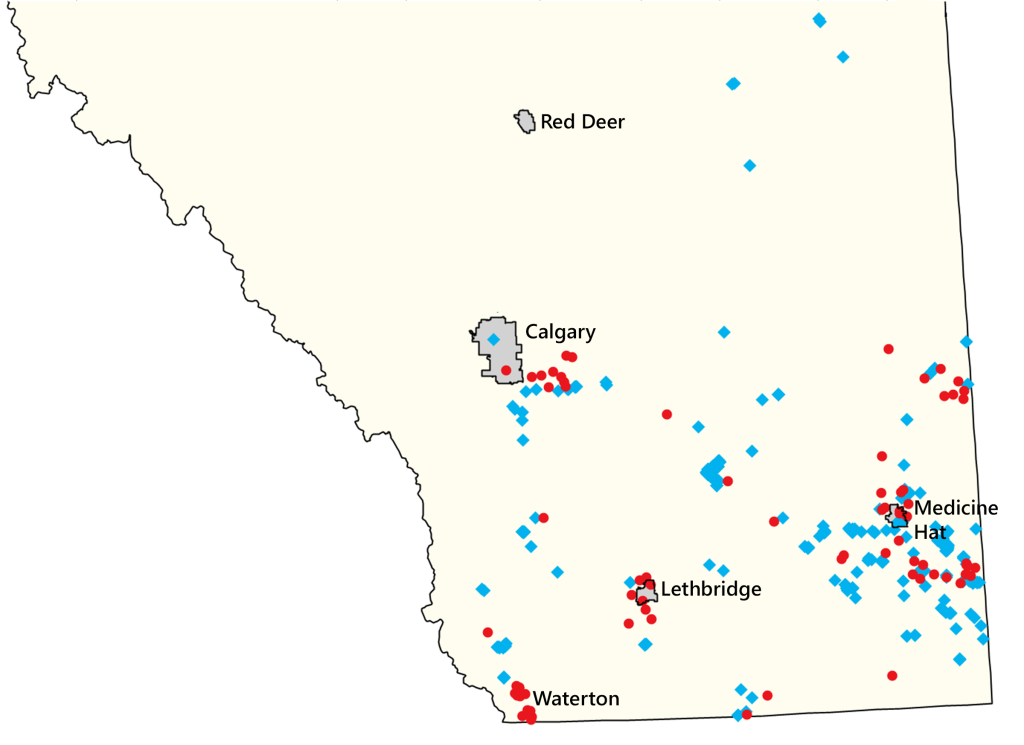

Map 1. The distribution of northern leopard frogs in southern Alberta, 2016–2021. The red circles are iNaturalist observations and the blue diamonds are from the government’s wildlife monitoring database (FWMIS). Though leopard frogs are still found throughout the grassland region, the population is fragmented and overall abundance is low. Prior to 1980, the frogs were also found in central Alberta and in the foothills, but few frogs remain in these regions today.

You can use your voice to speak up for the northern leopard frog. Consider writing to the Minister of Environment and Parks, Jason Nixon, to ask him why more is not being done to recover this threatened species in Alberta (aep.minister@gov.ab.ca). As a general rule, governments pay attention and provide resources to issues the public cares about. Therefore, part of the leopard frog’s problem may be its relative obscurity. It needs a higher profile as well as funding to pay for endangered species biologists and substantive habitat protection efforts.

You might also consider supporting groups such as the Nature Conservancy and other land trusts that protect prairie ecosystems through land purchases, donations, and easements. There are also groups that specialize in wetland conservation, such as Ducks Unlimited, the Alberta Riparian Habitat Management Society (Cows and Fish), and local watershed groups.

Though Alberta’s northern leopard frog populations are certainly struggling, they can recover if the necessary conservation steps are undertaken. It’s mainly a matter of getting enough people to care, and to translate that caring into appropriate management action.

References

- Environment Canada. 2013. Management Plan for the Northern Leopard Frog (Lithobates pipiens), Western Boreal/Prairie Populations, in Canada. Species at Risk Act Management Plan Series. Environment Canada, Ottawa, ON.

- Alberta Environment and Sustainable Resource Development (AESRD). 2012. Alberta Northern Leopard Frog Recovery Plan, 2010-2015. Alberta Environment and Sustainable Resource Development, Alberta Species at Risk Recovery Plan No. 20. Edmonton, AB.

- Kendell, K. and D. Prescott. 2007. Northern Leopard Frog Reintroduction Strategy for Alberta. Technical Report, T‐2007‐002. Alberta Conservation Association, Edmonton, AB.

Laura is a recent computer science and ecology graduate currently working in the field of artificial intelligence-based insect identification. She also keeps up her passion for herpetology and frog conservation through her small art business, Frog Tree Games (frogtreegames.com).

This article originally ran in Nature Alberta Magazine - Winter 2022.