Wild Boars on the March

Mature wild boars can weigh over 150 kg and have thick coats that allow them to survive Alberta’s harsh winters. CLOUDTAIL

If you were to design a species with maximal potential for invasive spread, which features might you include? A rapid rate of reproduction would certainly be high on the list, as would the ability to eat most anything and the ability to survive under a wide range of climatic conditions. For good measure, you might throw in high intelligence, stealthy behaviour, and the absence of effective predation. As it turns out, this creature already exists. It’s known as the pig.

Not just any pig, mind you. We are talking about Eurasian wild boars hybridized with domestic pigs. The origin of these animals dates back to the 1980s, when agricultural producers across Canada became enamored with raising exotic species for big profit. This craze brought elk farms, ostrich farms, and more to Alberta, including wild boars. Of course, warnings were issued by the environmental community and others about things that might go wrong. And of course, these warnings were ignored.

Over the years, some of the farmed wild boars escaped into the wild and hybridized with escaped domestic pigs. As highly adaptable omnivores, they have no trouble finding enough to eat. Plants, including tubers and roots, stems and leaves, and seeds and berries, are the main part of their diet. They also eat mushrooms, invertebrates, bird eggs, and small animals. Surviving our harsh winters does not pose a problem either because they are well protected by a woolly undercoat and are smart enough to create cattail shelters for riding out the worst weather.

Females can give birth to two litters per year of five to seven piglets each. TOMBAKO

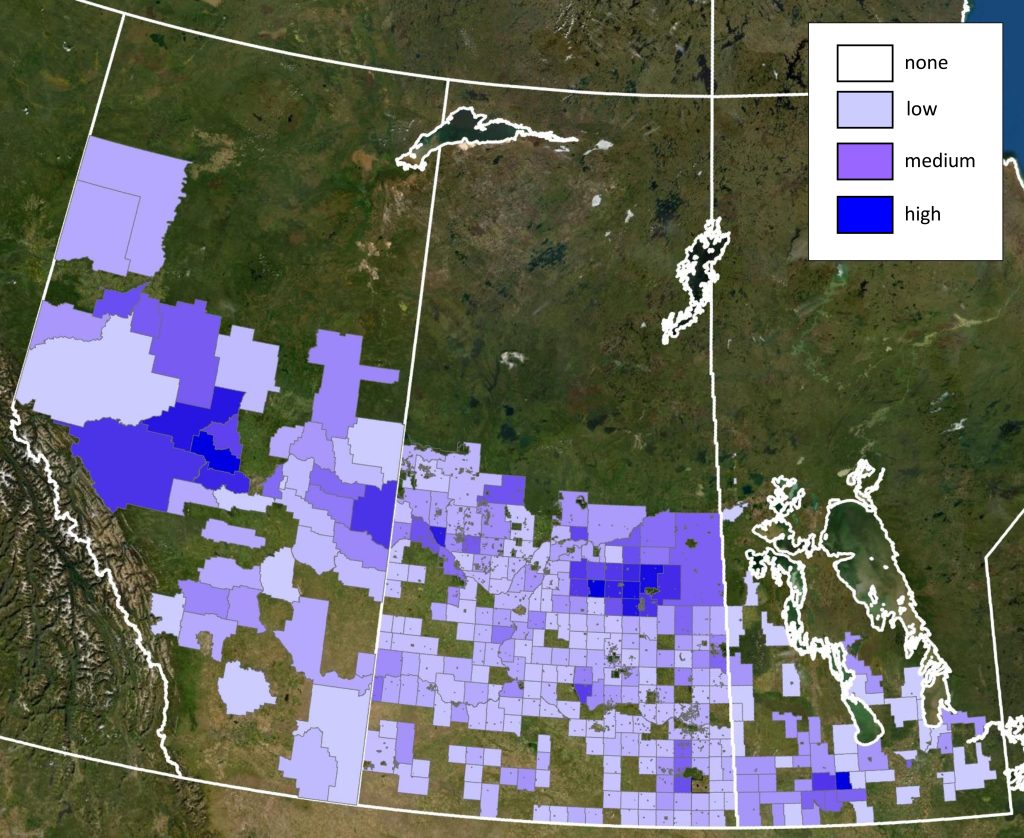

Initially, wild boar numbers were low and they went largely unnoticed. However, females become sexually mature at around ten months of age and thereafter can produce two litters of five to seven piglets each year. That’s a recipe for exponential growth, which is exactly what has happened. Today, wild boars are found throughout much of Canada, with the largest populations occurring in Saskatchewan and Alberta (see map). They prefer areas that provide a combination of forest cover and access to crops for feeding; therefore, densities are highest in the Parkland region of the Prairie Provinces. Wild boars are also found across much of the U.S.

Map of the distribution of wild boars across the Prairie Provinces. RYAN BROOK

Causes for Concern

Ironically, it is the agriculture industry, where the debacle began, that is suffering most from wild boars. The animals love to eat grain crops and they also damage crops through trampling. (This 45-second video is a real eye-opener: bit.ly/feralpigfield). Rooting behaviour causes extensive damage as well, especially in pastures. And hog farmers are extremely concerned about the potential for diseases to spread from wild pigs to their domestic herds.

Wild boars can also take up residence in urban areas, which they have done in many European cities with associated safety concerns. If you think that urban coyotes are a concern, imagine coming face to face with a 150-kg boar sporting two sharp tusks. Wild boars have already been sighted in Lamont, and the experts believe it is just a matter of time until they make their way into Edmonton and other cities.

Wild boars use their snouts to root for food, which results in extensive soil and vegetation disturbance. RYAN BROOK

What about their ecological impact? In media reports, wild boars are often cast as porcine equivalents of the Terminator, devasting everything in their path. However, in ecological systems, disturbance is not necessarily a bad thing. In days past, millions of bison ate and trampled vegetation and tore up the ground through wallowing. Beavers and ground squirrels are also expert land disturbers. Yet we laud these species as ecosystem engineers, helping to create habitat diversity. As for eating bird eggs, innocuous squirrels do this too, as do crows and coyotes, and many other species.

So, are wild boars then a positive ecological force, replacing some of the natural disturbances that are no longer active (such as bison grazing and prairie fires)? Not necessarily. Alberta’s native species have evolved together over millennia and have the adaptations needed to survive in each other’s company. As a newcomer to the scene, wild boars may present challenges that some species are ill equipped to handle. This is particularly the case for species already struggling to remain viable because of human impacts on the landscape.

A related problem is the potential for ecological imbalance. Because few medium- to large-sized predators remain in the settled parts of Alberta, predation is unlikely to keep boar populations in check. Nor is food supply much of a constraint, given their ability to eat just about anything and the ready availability of agricultural crops. Therefore, the potential exists for overpopulation. While ecosystems do require disturbance, there are limits beyond which ecosystem integrity cannot be maintained.

What to Do?

Hunting may seem like an obvious solution to the problem; however, experience has shown that it is ineffective for controlling populations. Boars are intelligent and quickly adapt to being hunted by becoming nocturnal and more evasive. Moreover, hunting can cause sounders (pig groups) to fracture and disperse. It also makes the boars more difficult to trap.

Trapping does work, but it is a complex, labour-intensive process because the entire group needs to be captured at once to be effective. Bait is set inside a fenced enclosure, which is then monitored by video camera. Once it is visually confirmed that all pigs are inside (which can take weeks), the door to the enclosure is closed via remote control.

The Alberta government has initiated a trapping program, along with a surveillance program to locate the boars. The public is asked to help by reporting sightings to af.wildboar@gov.ab.ca or by phoning 310-3276 (no area code needed). More information is available on the Alberta Invasive Species Council website: abinvasives.ca/fact-sheet/wild-boar-at-large

Given the wild boar’s invasive characteristics and widespread distribution, total eradication no longer seems feasible. But through ongoing surveillance and trapping, boar numbers can hopefully be kept low enough to avoid serious environmental damage.

This article originally ran in Nature Alberta Magazine - Fall 2022.