The Ronald Lake Wood Bison Herd: Observations From Their Home

By Garrett Rawleigh and Lee Hecker

When people think of bison, they often picture the vast herds of plains bison that once roamed the Great Plains of North America. These massive herds, and the story of their demise, are well known. But how many people are familiar with their larger northern cousin?

Wood bison are a distinct subspecies of American bison. Their historical range included Alaska and much of northwestern Canada, including the northern parts of the prairie provinces. Compared with plains bison, they are heavier, taller, darker coloured, and have a larger hump, all of which are adaptations that help them thrive in their northern homes. Wood bison were never as numerous as plains bison because there is much less forage available in their boreal habitat. The total Canadian population is estimated to have been less than 200,000 animals at their peak.1

Like the plains bison, wood bison were decimated over the course of the 1800s. However, while plains bison were entirely extirpated from Canada by 1900, a few small herds of wood bison remained in remote northern regions.1 Wood Buffalo National Park was established in 1922 to protect one of these remnant herds.

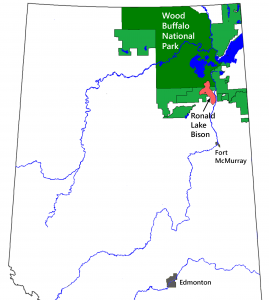

Map 1. The Ronald Lake bison herd, shown in red, ranges along the Athabasca River immediately south of Wood Buffalo National Park.

In the 1920s, a controversial decision was made to ship 6,673 plains bison from a captive herd in central Alberta to Wood Buffalo National Park.1 The primary motivation for shipping the animals north seems to have been that the captive herd had expanded beyond the capacity of its facility near Wainwright. Wood bison acquired tuberculosis and brucellosis from the translocated plains bison, who had themselves been infected through contact with cattle. In addition, the gene pools of these two subspecies became intermixed. For many years, it was thought that no pure wood bison stock remained. However, in the late 1950s a herd of 200 animals was found in the far northern portion of the park, and this herd became the foundation for wood bison reintroductions all around the world.

Today, there are approximately 3,000 bison in Wood Buffalo National Park and there are several free-ranging herds adjacent to the park. One of the satellite herds, located immediately south of the park and west of the Athabasca River, is called the Ronald Lake herd (see Map 1). This herd of approximately 300 animals has been the focus of our studies at the University of Alberta.

It was initially assumed that the Ronald Lake herd was a breakaway population of the Wood Buffalo National Park herd. However, local First Nations and Métis communities insisted the herd had always been separate from the park herds. Testing revealed that the Ronald Lake herd was disease free and genetically distinct from all other Alberta herds, supporting the community’s position. As a result, the herd was assigned a unique conservation designation, protecting it from all hunting besides Indigenous harvest for sustenance.

In 2011, an oil company acquired a lease to develop an oilsands mine within the range of the Ronald Lake herd. This prompted additional study of the herd, overseen by a multi-agency committee. We, along with other ecologists from the University of Alberta and Royal Alberta Museum, have served as scientific advisers to this committee, and we have been studying the herd’s ecology since 2017. Our experiences in the field led to some fascinating revelations about this remarkable herd.

In 2011, an oil company acquired a lease to develop an oilsands mine within the range of the Ronald Lake herd. This prompted additional study of the herd, overseen by a multi-agency committee. We, along with other ecologists from the University of Alberta and Royal Alberta Museum, have served as scientific advisers to this committee, and we have been studying the herd’s ecology since 2017. Our experiences in the field led to some fascinating revelations about this remarkable herd.

In prairie habitats, there is an abundance of the graminoids (grasses and other grass-like plants such as sedges) that bison prefer to eat. But the Ronald Lake herd’s range is a mosaic of mostly deciduous and jack pine forests with scattered pockets of graminoid-dominated wetlands. This is a challenging habitat for grazers.

The herd has adapted to its environment by changing its foraging behaviour throughout the year. In the spring, they target graminoids, especially wetland sedges, which are high in energy. This allows them to replenish their stores, which are depleted after eating plants that are low in energy and protein all winter. In the summer, they switch to eating more herbaceous and woody plants such as fireweed, prickly rose, and red-osier dogwood, which are loaded with protein and help the bison add mass. When winter comes around they are stuck eating dead graminoids again, the only leafy vegetation available. Subsequently they lose weight, and the cycle restarts.

An interesting characteristic of bison foraging behaviour is their selectivity during winter. Bison use their massive heads to plow through snow-covered wetland meadows to access the buried sedge. These plowed areas are referred to as craters. We observed a great variety in crater size and a surprising degree of selectivity in the plant species consumed. We regularly found larger craters in wetlands dominated by one species in particular: wheat sedge. Bison devoured this species down to the frozen ground and left other graminoid species right next to these plants untouched.

Wet meadows are a favoured foraging site of wood bison. LEE HECKER

Travelling between the scattered wetlands that contain their preferred forage is challenging for bison. To minimize energy loss and predation risk, bison tend to travel along well-established trails they help to create. These trails take advantage of ridges and other natural features that minimize the amount of time spent slogging through wetlands. Our trail cameras have captured images of dozens of bison travelling along these trails in single file. Bison use these trails so consistently that fallen trees on the trail have their bark rubbed off from recurrent bison-belly friction.

The bison trail system functions as a wildlife highway, opening clear paths through the forest for black bears, moose, wolves, deer, lynx, foxes, and even otters. This is an example of how bison engineer their environment in ways that benefit other species. In addition, during winter, wood bison act as nature’s snowplows, cutting deep, wide paths through the drifts. We regularly observed tracks of other animals, particularly moose and wolves, using these prepared paths.

Perhaps the most interesting aspect of the Ronald Lake herd’s movement is its annual migration. Each spring, over a period of approximately ten days, females from across the range gather in an upland meadow at the base of the Birch Mountains. Some females travel up to 40 km to meet others at this location. Initially, we thought that bison congregated at the meadow to have their calves. However, images from trail cameras on the migration corridors show that at least some females are travelling with calves in tow. Therefore, we now believe the meadow serves as a nursery ground. The openness of the meadow allows adults to keep an eye out for predators and the solid ground allows for easy escape if pursued. Furthermore, the timing of the migration coincides with the green-up of vegetation in the meadow, allowing the bison to replenish themselves with nutrient-rich and easily digestible plants after a long, hard winter. This migration to a nursery ground is something unique to the Ronald Lake herd and has not been observed in other groups of wood bison.

A small group of juvenile wood bison. RICHARD SCHNEIDER

When we encountered bison in the field, they were typically in sub-herds of 20 to 30 individuals composed of adult females and mixed-sex juveniles and calves. The response of these herds to our presence revealed a variety of anti-predator behaviours. These behaviours depended on where the bison were and what they were doing. While wallowing, the herd generally gave us their full attention but did not immediately bolt. Rather, the older females formed a woolly wall between us and the young. If we did not move away, an adult bison would break away from the wall and take a few hurried steps towards us, sending a clear message to get going. We also observed herds use a double-ringed structure in the winter when bedded. The adults formed a protective outer wall and the young ones lay together in the centre. If we encountered a herd foraging in a wetland, they would immediately take off running. But they generally did not go far. Instead, they would run five to ten metres into the adjacent forest and then form their defensive lines on stable ground. After a while, they slowly advanced back toward their feeding area, unwilling to expend unnecessary energy travelling to a new wetland.

Our research into the Ronald Lake herd’s ecology contributes to the latest chapter in the history of this herd. But there is still much more to learn about them. Moving forward it will be important to get the local communities more involved to expand our knowledge of the herd. We would not know how uniquely special this herd is without the outspoken voices of Indigenous communities. Coupling our modern scientific approach with traditional ecological knowledge will provide invaluable insight into the factors motivating the herd’s behaviour. Managing a population like this takes a community to figure out not just where, but why the buffalo roam.

References

- Lauren Markewicz, 2017. Like Distant Thunder: Canada’s Bison Conservation Story. Parks Canada.

Garrett Rawleigh was born and raised in southern Alberta and has been interested in wildlife since he was young. After finishing a bachelor's degree in environmental science, he joined the Ronald Lake Bison Project at the U of A and hopes to continue working with the herd in the future.

Lee Hecker came out west from Maine to study rattlesnakes, but instead earned his PhD at the University of Alberta studying bison. Lee intends to pursue a career in ecology and conservation research.

This article originally ran in Nature Alberta Magazine - Summer 2022.