Collaborating for Protection: Conservation Easements and the Waldron Ranch Grazing Co-operative

The western part of the Waldron Ranch is in the Montane Natural Subregion, featuring rolling hills with interspersed forests and open grasslands. RICHARD SCHNEIDER

BY FOREST HISEY AND JONAH OLSEN

The Eastern Slopes of the Rockies have been home to countless generations of Indigenous Peoples and settlers who have benefitted from the landscape. Watching sunshine glint off those peaks calls to mind Aldo Leopold’s “Thinking Like a Mountain” metaphor, where mountains serve as an ecological lens across the centuries.

The Waldron Ranch has established a conservation easement in collaboration with the Nature Conservancy of Canada, protecting over 120 km2 of intact grassland habitat. FORREST HISEY

With much of southern Alberta now privately owned and used for agriculture, ecosystems are visibly impacted by a network of cultivated fields, roads, fences, and other barriers. The lack of ecological protections for private land in Canada creates a precarious reality for biodiversity.

Landowners have the right to use their land according to personal motivations, and most need to earn a living from it. Fortunately, many ranchers and farmers consider land stewardship to be important. And for some, it is a priority. Such concerned landowners may take bold measures, safeguarding their property’s economic and ecological sustainability through collaborations with conservation organizations.

The Waldron Ranch Grazing Co-operative is a prime example. The Ranch has entered a partnership with the Nature Conservancy of Canada to protect over 120 km2 north of Pincher Creek using a conservation easement. Using the Waldron Ranch as a case study, we can gain insight into landowner motivations and the practical application of conservation easements.

Conservation Easements

Conservation methods need to be tailored to fit the local form of land ownership. On public lands, biodiversity conservation can be advanced through government rules and policies. But the government has limited ability to dictate what happens on private land. Therefore, biodiversity protection on private land is usually pursued through voluntary measures, and one of the most important tools is conservation easements.

Golden eagles and other raptors are drawn to the grasslands of the Waldron Ranch because of the abundance of small mammals. RICHARD SCHNEIDER

Conservation easements are voluntary legal agreements between private landowners and conservation organizations that entail the sale of specified property rights to the conservation organization. The terms are negotiated between the parties and can take many forms. Restrictions can include limiting development, limiting clearcutting, or permitting public access. These are unique to each property, with restrictions based on landowner needs such as cattle grazing, sustainable timber harvesting, or infrastructure maintenance. The agreements typically run in perpetuity, but in some cases may be for a specified period of time. A key point is that the agreement is tied to the land itself. This transforms easements from a contractual right to a property right that future owners must also abide by.

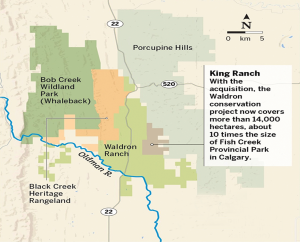

The Waldron Ranch is located in southern Alberta, just north of Pincher Creek. NATURE CONSERVANCY OF CANADA

Conservation easements became popular in Canada in the 1990s, when most provinces and territories passed legislation enhancing private land conservation. For example, in 1995, Alberta’s Environmental Protection and Enhancement Act was amended to include easements as a tool for private land conservation, paving the way for their stewardship and care. Easements were incentivized in the late 1990s by changes to tax laws and the creation of the federal Ecogift program. Through the Ecogift program, easements are registered and provide tax relief and recognition of stewardship.

Motivations

Conservation is facilitated by a diverse web of individuals and groups who must weigh economic realities against altruistic goals. Motives and values are essential to property decisions regarding biodiversity conservation. Intrinsic motivations relate to personal satisfaction. These connect management decisions to values and ethics, often focusing on individual and community impacts. Some landowners care deeply about being attached to a place, the local environment, and the culture that develops there. Extrinsic motivations relate to external factors such as financial benefits from tax relief or direct payments. These positive factors may be tempered by concerns about giving up control, especially if a landowner depends on growing crops or running cattle for family income.

The eastern part of the Waldron Ranch is in the Foothills Fescue Natural Subregion, featuring open grasslands and flatter landscapes. FORREST HISEY

Successful conservation on private lands requires a willingness by both parties to be flexible. Multigenerational landowners have intimate knowledge of their property, creating moments for collaborations which shift, but not erase, existing land uses and local cultures. Conservationists working with passionate landowners should pursue protection objectives while recognizing existing practices and building trust and respect. Doing so reinforces sustainable land uses, encourages further participation with local communities, and showcases the benefits of working-land livelihoods.

Co-operatives

Co-operatives are independent, democratic associations of individuals who have organized to meet collective socio-economic and cultural needs. Early Canadian co-operatives emerged in the mid-19th century, and in western Canada many took the form of agricultural mutual insurance companies. By the late 19th century, co-operatives had become a significant force in the rural Canadian economy, particularly in ranching, dairy, and grain production. Eventually, towards the turn of the century, provincial governments began to provide economic and legislative support for co-operatives. By the 1930s, the prairie provinces had the nation’s strongest regional co-operative movement.

Despite these co-operative roots, Albertan culture is also characterized by “rugged individualism.” This distinct context can be understood through geographic differences — whereas Saskatchewan and Manitoba have long been predominantly farming provinces, Alberta, and the southwest in particular, is characterized by ranching, an industry defined by entrepreneurial identity. Waldron Ranch, and the Albertan ranching co-operative movement in general, should be understood in this context, at the crossroads of individualist entrepreneurialism and democratic organization.

Columbian ground squirrels are a common sight on the Waldron Ranch. RICHARD SCHNEIDER

The Waldron Ranch Conservation Easement

For millennia, the lands of the Waldron Ranch were home to Indigenous Peoples. The Ranch, originally called the Walrond Cattle Ranche, was established in 1883 as settlers spread west. In 1962, after the land had passed through various owners, a group of 116 ranchers and farmers decided to co-operatively purchase the Waldron, showcasing the attractiveness of co-operatively owning grazing land. Sustainable management has been a hallmark of Waldron Ranch; the co-operative has kept the land healthy for over 50 years by using innovative practices and working with experts.

In 2013, the Nature Conservancy of Canada and Waldron Ranch collaborated to establish a conservation easement, perpetually protecting approximately 12,000 ha of land. The easement occupies a large stretch of contiguous native grassland, an endangered Albertan ecosystem with little remaining intact. The easement conserves habitat for at-risk species like grizzly bears and ferruginous hawks, and provides critical protections for rivers that benefit prairie communities.

The Co-operative received a payment from the Nature Conservancy for the easement, which they used to purchase a nearby ranch, roughly doubling their land holdings. They then placed a similar easement on that ranch, again receiving the payment, while increasing the amount of protected native Albertan grassland. In addition to these payments, the Co-operative is provided yearly funds for maintenance and improvement of existing infrastructure. The easement was an ideal conservation tool because it did not impact the Ranch’s ability to continue grazing, while providing financial opportunities for expansion.

Comments we heard during our interviews with members of the Co-operative illustrate their thinking:

“I think we have the same objectives... they’re [the Nature Conservancy] interested in wildlife preserving... we’re interested in healthy habitat for animals for our livestock.” —Participant 2

“You can’t subdivide it; you can’t cultivate it... can’t develop on it. So, we can’t put up a hotel out there... Now we didn’t want to do that anyway.” —Participant 3

When asked about the impacts from the easement, all participants agreed that day-to-day operations hadn’t changed. The restrictions include no breaking, cultivation, or development of grasslands. These restrictions fit the Co-operative’s mission, as they would negatively impact grazing. For the average rancher, nothing changed. Impacts were mainly felt by the board of directors, where long-term planning occurs. The easement also included increased rotational grazing (which was already being used) and wildlife-friendly fences.

Wildflowers, such as this sticky geranium, are plentiful in the native grasslands of the Waldron Ranch. RICHARD SCHNEIDER

The Place for Landowners in Biodiversity Conservation

Conserving the Waldron, one of the largest ranches in Canada, showcases how landowners and conservation organizations can collaborate for private land conservation. Landowners are critical to work with when combating the crises of biodiversity decline and climate change. Owning property is a right and a responsibility. Landowners have the inalienable right to benefit from the land, and yet even more fundamental is the responsibility to the broader ecological community calling that land home.

Considering responsibilities in the same breath as rights must become commonplace. As citizens, we have duties to our communities (human and non-human). Landowners who occupy this role have a special understanding of property ownership, incorporating a view like Leopold’s mountain. Using land with consideration toward future generations of all species is necessary in pursuit of a sustainable and equitable future. By degrading our landscapes, we degrade our communities and ourselves, as the imagined separation of nature and society tempts violent acts against the very places which sustain us.

The Waldron Ranch presents a fascinating case, uniting the seemingly contradictory motivations of individual ranchers with the collectivist co-operative. Equally striking is the ranchers deciding to place a conservation easement on their land — dedicating private property for the public good in perpetuity. Ultimately, private land conservation requires passionate landowners weighing complex values as they balance conservation practices with their livelihoods. For easements to be a successful strategy, it is necessary for conservation organizations to understand the realities of landowners, especially if trust is to be developed across geographic and ideological boundaries.

Acknowledgements: We thank the Waldron Ranch Grazing Co-operative and the Nature Conservancy of Canada for agreeing to be interviewed and welcoming us to their land.

Forrest Hisey is a PhD candidate studying Human Geography at the University of Toronto, Mississauga. His research focuses on biodiversity conservation in his home province of Alberta and western Canada. Now splitting time between Toronto and B.C., Forrest enjoys working with local communities and escaping to fly fish whenever possible.

Jonah Olsen is a PhD candidate in Human Geography at the University of Toronto and a Visiting Researcher at Mondragon Unibertsitatea in Spain. His research considers the possibility for economic alternatives in socio-economic, political, and cultural context, focusing on the Basque Country and Italy. As a Manitoban, Jonah is also fascinated by prairie history and the Canadian co-operative movement.