The Swift Fox: A Canadian Conservation Success Story

BY LU CARBYN, NIKKI PASKAR, KRISTY BLY, AND RICHARD SCHNEIDER

Clocked at 60 kilometers an hour, the swift fox is the fastest member of the wild dog family in North America. It’s also the smallest, roughly the size of a house cat. Its home is the open prairie, and it once ranged across much of the Great Plains of North America. Active mostly at night, it is an opportunistic predator that eats a wide variety of small mammals, birds, insects, and other small creatures. During the day it is usually hidden away in a burrow, except when playing with pups in summer or sunning itself in winter. In contrast to other canids, it uses burrows all year long to stay safe from larger predators and extreme weather.

Swift foxes were once common on the Canadian Prairies, but populations underwent precipitous declines in the late 1800s with the influx of Europeans to the West. By 1900, reports of swift foxes were rare in Canada and the northern United States. The last Canadian sighting was made near Manyberries, Alberta, in 1938. In 1978, the swift fox was officially designated as extinct in Canada, though fortunately some populations persisted in the U.S.

An initial contributor to the decline was unsustainable trapping in the 19th century. Later, with the influx of settlers, swift foxes also became unintentional victims of poisoning programs to kill wolves and coyotes on the plains. In addition, campaigns by ranchers and farmers to kill badgers, prairie dogs, and ground squirrels reduced the number of escape holes and denning sites. But the overriding factor in the decline of swift foxes was the transformation of the natural shortgrass prairie ecosystem, dominated by bison herds, to one of croplands dominated by the plough.

With the disappearance of bison from the plains, scavenging opportunities for swift foxes were much reduced and the simplified grassland ecosystem supported fewer small prey. With the concomitant loss of the plains wolf, coyote populations increased and became a major cause of swift fox mortality. Finally, a large proportion of swift fox habitat was converted to cropland and tame pasture.

The Reintroduction Program

Efforts to restore swift foxes in Canada began in the mid 1970s, and many individuals and agencies were involved over time. The first release of foxes was actually an illegal one. A game farm owner released four captive foxes from his facility onto the prairies. No permits, no studies, no health checks — just a brazen effort to gain publicity. It was even filmed.

More structured efforts soon followed. As a first step, wild foxes were imported and raised at a wildlife facility near Cochrane and at three zoos. It turned out that these little carnivores took exceptionally well to being raised in captivity and they became the stock for future releases, augmented by additional wild-caught foxes. By the early 1980s, a formal reintroduction program was underway, involving the federal and provincial governments, the University of Calgary, and several zoos and conservation organizations. It was an ambitious collaborative effort.

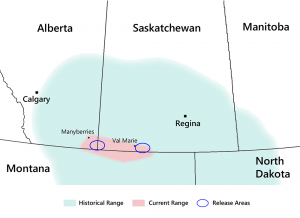

Map: The historical and current range of northern swift foxes. The two reintroduction areas are also shown. R. Schneider.

Fox releases began in 1983 and continued until 1997. The releases occurred within the core of the historical Canadian range, in two main areas: one centred on the border between Alberta and Saskatchewan, and the other in south-central Saskatchewan (see map). A total of 932 foxes were released. Of these, 841 were reared in captivity — the descendants of 17 wild pairs from Colorado, Wyoming, and South Dakota. The remaining 91 releases were wild foxes obtained from Colorado and Wyoming.

Initial releases involved a technique known as the “soft” release method, in which pairs of foxes were penned and fed over winter at selected prairie sites. These pairs would mate and produce pups. Once the pups were large enough, the pens were opened and the foxes were free to leave but could still use the pens as shelter. A second method, termed the “hard” release, was subsequently used, in which wild-caught stock and captive-reared foxes that were old enough to disperse were released directly into the wild.

The overall program to 1997 cost an estimated $5 million and was highly successful. After the first surveys in 1991, an estimated 250 or more swift foxes were roaming wild and free in Canada. The species was sighted, or recorded as present, in at least 278 sections of land in southern Alberta and southern Saskatchewan. By then there were also 12 records of swift foxes in northern Montana that had originated from the Canadian reintroduction program. Good news for both countries.

The population estimate from the latest survey, in 2015, is 870 individuals spread across an area of 23,964 km2 spanning the Canada-Montana border. Although populations have fluctuated over the decades since the program began, the core populations have persisted, making the swift fox reintroduction effort one of the most successful mammal reintroduction programs in North American history. Following the reintroduction program, the official status of foxes in Canada was changed from Extirpated to Endangered and then to Threatened, in 2009.

The U.S. Dimension

Swift foxes in the U.S. also experienced major declines in the 19th century; however, there were significant regional differences. Populations in the southern Great Plains persisted, whereas populations in the north (i.e., Montana, North Dakota, South Dakota) were largely extirpated. This suggests that factors specific to the northern part of the swift fox range, such as winter climate, may have been a contributing factor in the eventual loss of the species in these areas.

The successful Canadian reintroduction program became a prototype for U.S. reintroduction efforts, which began in 1998; three in Montana and three in South Dakota. These reintroduction efforts were augmented by the natural migration of Canadian swift foxes across the border into Montana. Today, swift foxes occupy about 40% of their former range in the U.S.

Despite these valiant efforts, the Canada/Montana swift fox population remains separated from the larger core population to the south. Why an estimated 322-km gap exists between these populations is unclear. Models evaluating swift fox habitat indicate suitable habitat exists, though the presence of large rivers and highways could serve as barriers to expansion.

Hopefully, if both the northern and southern populations continue to grow, dispersing foxes will eventually occupy available habitat in the gap. Connecting the northern population to the larger southern population is an important conservation goal. It will ensure that genetic diversity of the northern population is maintained and it will provide the population with greater resilience to changing environmental conditions.

The Role of Public Rangelands

Another dimension to the swift fox story is the availability of suitable habitat. Much of the Canadian swift fox population has been using native grasslands that, up to 2012, had been administered as Prairie Farm Rehabilitation Administration (PFRA) lands. The PFRA was a federal program initiated in response to the prolonged drought in Western Canada in the 1930s. Under this program, community pastures were created with the goal of rehabilitating and conserving eroded or fragile land. A total of 85 pastures encompassing more than 9,000 km2 were ultimately operated under the PRFA: 24 in Manitoba, 60 in Saskatchewan, and 1 in Alberta near the Suffield Military Base.

The PFRA program ran for decades and was widely thought to be one of the most successful grassland conservation efforts in Canada, addressing some of the prairies’ most pressing problems. However, the Harper government disbanded the program in 2012, asserting that the program had fulfilled its original intent. The PFRA lands were transferred to the provinces over the following six years.

Given how successful the program had been, its termination provoked a strong public backlash. Concern was highest in Saskatchewan, where the provincial government had signalled its intention to sell the PFRA pastures, along with the province’s own community pastures, to private owners. In response to public pressure, the Saskatchewan government conducted a survey and engaged in stakeholder consultations. The message was clear. A strong majority of participants were against land sales and placed a higher importance on ecological preservation of the land than economic opportunities (GOS 2017).1 Nevertheless, the province has continued to sell Crown lands to existing lease holders and via public auction. For example, according to the Ministry of Agriculture Annual Report, over 26,000 acres were sold in 2019-2020.2 Smaller-scale sales of Crown grasslands have also occurred in Alberta.

Post-Reintroduction

Following the reintroduction program, wildlife managers focused their efforts on ensuring that the new swift fox population would grow and remain viable over the long term. A key step, as required under the Species at Risk Act, was to characterize critical habitat for the foxes and to determine where it existed on the landscape. Additional effort went into understanding the impacts of human land uses on swift foxes. The results of these studies, and appropriate management responses, were captured in a federal action plan published by Environment and Climate Change Canada in 2017.3

Swift Fox by Myrna Pearman

A notable feature of the action plan was that it focused on a specific region — southern Saskatchewan — rather than a specific species. Wildlife managers recognized that the challenges faced by the swift fox were shared by other threatened grassland species and that more could be accomplished by conserving the entire grassland community than by trying to manage each species separately. At heart, this was a regional issue that required a regional management approach. Therefore, the action plan applied to nine species at risk and four species of special concern.

Managers also understood that habitat disturbance per se was not the problem. Historically, the grazing, trampling, and wallowing of millions of bison had an enormous impact on grassland systems. So did fire. The problem with human-origin disturbances is that they differ in significant ways from natural disturbances that native species are adapted to. For example, we try to eliminate ground squirrels and anything else that tries to eat our calves or crops. We stop fires. We introduce foreign species as forage crops. The list goes on.

If species conservation was the only objective that mattered, the obvious solution would be to put bison and fire back on the landscape and allow predators to roam freely. This is in fact what is happening on a large scale in Montana, where wealthy philanthropists are building the American Prairie Reserve. Through a non-profit foundation, ranches are slowly being purchased from willing sellers, and cows are being phased out and replaced with wild bison (originating from Elk Island National Park). The idea is to stitch these private properties together with vast tracts of neighboring public lands to eventually create one giant, rewilded prairie over 12,000 km2 in size. (Visit americanprairie.org for more information.)

A similar effort is happening on a smaller scale in Grassland National Park in southern Saskatchewan. Habitat restoration efforts are underway and a successful bison reintroduction program has taken place. However, at least for now, there are no plans to significantly increase the size of the park beyond its current 900 km2.

Though the rewilding efforts in Montana and Grasslands National Park are very promising, the hard reality is that they account for only a fraction of one percent of prairie grasslands. The remaining lands have all been allocated to ranching and farming. The implication is that the future of swift foxes and other threatened grassland species will depend in large part on gaining the cooperation of ranchers and farmers in supporting conservation.

The forestry sector provides us with a workable model. As a guiding principle, forestry companies (at least the progressive ones) try to make their harvesting operations approximate natural disturbances as closely as possible. While this approach is not practical on cultivated agricultural lands, it holds great promise on the vast rangelands that constitute the core habitat of swift foxes and other threatened grassland species. Cows are clearly not bison, but it is possible to approximate many of the key ecosystem effects of bison through careful management of cattle grazing patterns and intensity. Other important steps include retaining native grass species, retaining natural wetlands, stopping ground squirrel eradication programs, applying prescribed fire where practical, and minimizing roads and other infrastructure.

The main challenge in implementing these ideas is gaining the support of the agricultural community. This brings us back to the issue of land ownership and the PFRA. Once public lands are sold to private owners, the government has very little control over how it is managed. Land ownership conveys strong property rights, which governments are reluctant to challenge for fear of political backlash. Moreover, a heavy-handed approach would likely do more harm than good because conservation efforts on private lands will ultimately depend on the actions, and hence goodwill, of ranchers. This is why it is so important to retain the public ownership of rangelands, and why Crown land sales need to stop.

On Crown lands there is greater scope for conservation, since the lands must be managed in the broad public interest. Moreover, provincial governments must adhere to the conservation requirements prescribed by the Species at Risk Act. Nevertheless, the ranching community still has a powerful voice in what happens — or does not happen. Consequently, the path forward must still entail education and collaboration.

Progress could be greatly improved if provincial governments made grassland conservation a higher priority and provided greater guidance and resources to the ranching community for conservation. How can we expect ranchers to change their practices when their government remains wedded to goal of optimizing productivity? The conservation-minded public should demand this of its elected officials. It is only through such pressure that significant change will occur.

For now, the swift fox appears to be holding its own. The population declined somewhat in the last survey, in 2015, rather than continuing its growth trajectory. Hopefully, this was just a hiccup attributable to a bad winter. Time will tell. But clearly, if we want the swift fox to thrive in the years ahead, it’s up to us to provide it with a good home.

References

- Government of Saskatchewan, 2017. Saskatchewan Provincial Pastures Land. https://www.saskatchewan.ca/-/media/news-release-backgrounders/2017/june/2017-pasture-land-summary.pdf

- Saskatchewan Ministry of Agriculture, 2020. Annual Report for 2019-20. https://publications.saskatchewan.ca/api/v1/products/106879/formats/119942/download

- and Climate Change Canada, 2017. Action Plan for Multiple Species at Risk in Southwestern Saskatchewan: South of the Divide. https://www.publications.gc.ca/site/eng/9.847179/publication.html

Table 1

| Reintroduction | # Swift Foxes Released | # Years |

| Saskatchewan and Alberta, Canada | 942 | 15 (1983-1997) |

| Blackfeet Indian Reservation, MT | 123 | 5 (1998-2002) |

| Bad River Ranches, SD | 226 | 6 (2002-2007) |

| Badlands National Park, SD | 88 | 3 (2003-2005) |

| Lower Brule Indian Reservation, SD | 84 | 2 (2006-2008) |

| Pine Ridge Indian Reservation, SD | 79 | 2 (2009-2010) |

| Fort Peck Indian Reservation, MT | 60 | 3 (2006, 2009, 2010) |

| Fort Belknap Indian Reservation, MT | 27 | 1 (2020) |

Lu Carbyn is an adjunct professor at the University of Alberta and a retired Canadian Wildlife Service research scientist.

Kristy Bly is a senior wildlife conservation biologist for the World Wildlife Fund’s U.S. Northern Great Plains Program

Nikki Paskar is a conservation coordinator with the Edmonton & Area Land Trust.

Richard Schneider is a conservation biologist and serves as the Executive Director of Nature Alberta.

This article originally ran in Nature Alberta Magazine - Spring 2021.