Diminished Chorus: The Decline of Grassland Birds

The chestnut-collared longspur population in Canada has declined steeply since 1970 at a rate of more than 5% per year and they are listed as Endangered by COSEWIC. DAVID BELL

BY NANCY MAHONY

Few people are lucky enough to experience the dawn chorus on Alberta’s native grasslands — a bewildering concert of ringing trills, melodious gurgles, and jumbled songs. I’ve had the good fortune to do so on many May and June mornings, as a biologist researching grassland songbirds at one of Canada’s largest remaining native prairies, the Suffield National Wildlife Area near Medicine Hat.

What struck me when I first started working on the prairies was the unique and impressive aerial displays used by many grassland birds. Unlike other habitats in which I had worked, where birds sang from shrubs and trees to defend territories and attract mates, there is not much vertical structure in native prairie. So grassland birds must take to the wing to get their message across.

Male Sprague’s pipits are the true masters of this behaviour, flying up to 100 m above the ground while singing — a mere speck against the sky when seen from below — before diving to the ground at dizzying speeds. Horned larks, while not going nearly as high, do a similar fluttering aerial display while singing their tinkling, bell-like song. Thick-billed longspur males fly dozens of metres above the ground, hold their wings outstretched to display white wing linings, and then spread their tails and float downward while singing. The agile chestnut-collared longspurs chase each other in looping mid-air aerobatics. And large shorebirds, such as long-billed curlews and marbled godwits, take to the sky to circle and loudly scold unwary predators — and biologists — who happen to encroach on their territories.

The Baird's sparrow population across the Canadian prairies has declined by more than 50% since 1970. The Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada (COSEWIC) assessed this species as Special Concern. CONNOR CHARCHUK

Not all grassland species are acrobatic though. Species such as vesper and grasshopper sparrows use small shrubs or stout patches of grass or flowers as singing perches. Elusive Baird’s sparrows sing from patches of thicker vegetation, making them hard to spot.

In contrast to the highly visible males, female grassland birds have more camouflaged plumage and stay closer to the ground, the better to hide them and their nests from predators. These adaptations to the wide-open, windswept prairies evolved over thousands of years and have allowed birds to take advantage of all types of grasslands and the many micro-habitats within them, resulting in a rich and varied bird community.

When I’m counting birds or searching for hidden nests out on the prairie, without a road, power line, fence, or crop field in sight, it is easy to imagine the vast unbroken native grasslands that once stretched from the edge of the Canadian Shield in Manitoba to the foothills of the Rocky Mountains. Unfortunately, this is a rare sight today. Approximately 75% of Canada’s native grasslands have been plowed up for crop production or converted to tame pasture since the beginning of European settlement of the west.1

Temperate grasslands rank among the most imperiled and least protected ecosystems on Earth. In 2008, the International Union for the Conservation of Nature declared them the world’s most endangered ecosystem. To make matters worse, the conversion of native grassland to crop production is still ongoing. From 2018–2019 alone, an estimated 1.1 million hectares of grassland were plowed up in Canada and the U.S., primarily for row crop agriculture.2 Agricultural practices have also become more intensive over the years, with less and less natural structure left on the land.

Canada has lost 75% of its native grasslands, and their destruction continues. In 2018–2019, over 1 million hectares of grassland were plowed up in Canada and the U.S. to make way for row crop agriculture. CONNOR CHARCHUK

It is worth noting that native grasslands dedicated to cattle grazing, rather than growing crops, can support grassland bird populations as long as appropriate management practices are used (e.g., livestock rotation, water source management, and stocking rates). Properly managed rangelands also serve as carbon sinks, storing carbon underground in thick, deep root systems. There is currently an increase in research exploring how sustainable livestock grazing may have beneficial effects on biodiversity, including birds, and carbon sequestration.

Agricultural pesticides are an additional concern. There is evidence that pesticides cause direct mortality and alter food availability for birds. Recent reports have found equally negative impacts of habitat loss and pesticide use on population trends of North American grassland birds.3

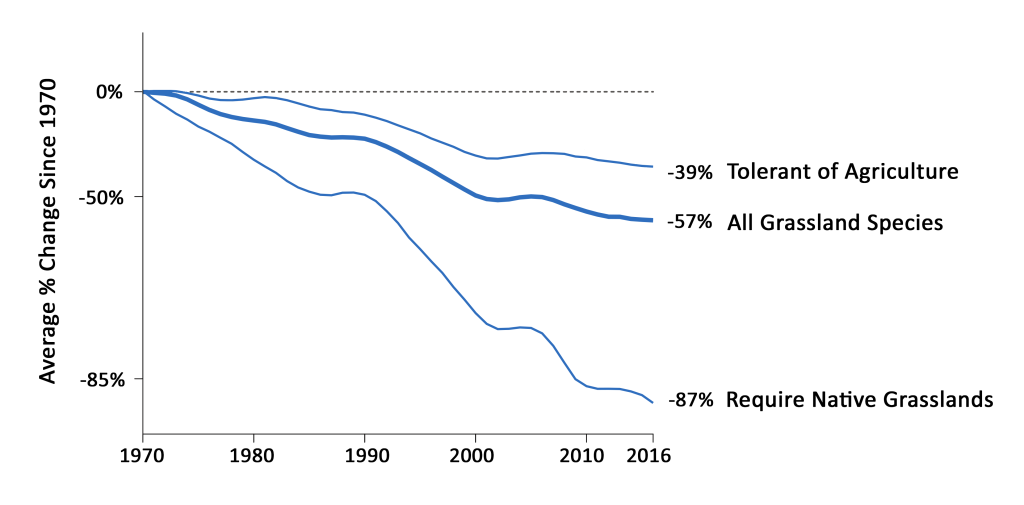

With such overwhelming agricultural impacts, it is not surprising that North American grassland bird populations continue to decline, despite decades of conservation concern. In Canada, grassland bird abundance has declined by 57% since 1970, with species dependent on native grassland being particularly hard hit, with declines of 87%. Even those that are more tolerant of agriculture have declined by 39%.4 Our grasslands have lost 300 million birds in the last 50 years.

Nat Hontar (right) weighs a horned lark, Emma Sherwood prepares bands, and David Bell records data as part of ongoing research of grassland birds at Suffield National Wildlife Area. NANCY MAHONY

It is within this somewhat dire context that I do research on grassland songbird conservation for Environment and Climate Change Canada. Many grassland birds have been designated as Species at Risk in Canada, including the chestnut-collared longspur (endangered), thick-billed longspur (threatened), Sprague’s pipit (threatened), Baird’s sparrow (special concern), and the horned lark, which is currently being assessed. My work is focused on understanding how landscape change is driving population declines in these species throughout their full life-cycle, including the breeding season here in Canada as well as migration and wintering in the U.S. and Mexico, where similar agricultural conversion is happening.

My work at the Suffield National Wildlife Area has confirmed the importance of large, intact grassland areas. Breeding Bird Surveys show that, across the prairie potholes region of North America, ten of the 16 grassland bird species I studied declined between 1994–2016. However, within the largely intact Suffield region, only one of these 16 species — the horned lark — declined over the same period.

Grassland bird populations in Canada have declined by 57% since 1970. Native grassland specialists have been particularly hard hit, with declines of 87%, but even those somewhat tolerant of agriculture continue to decline. (Modified from the State of Canada’s Birds 2019.) NABCI CANADA

Much of my research has focused on nesting success and over-winter survival of horned larks and chestnut-collared longspurs. To determine nest success, my team spends a good portion of May to July at Suffield looking for nests. Each species manages to find ways to hide their nests on the ground, employing different strategies to keep them hidden from predators.

Horned lark nests are quite open to the elements, but an incubating female provides good camouflage. DAVID BELL

Horned larks choose sites with bare ground or with very sparse vegetation next to a clump of grass, pasture sage, or a cow patty. The nests seem dangerously open to the elements and the prying eyes of predators, but once a female sits on the nest, her light brown plumage provides excellent camouflage. The birds are also extremely wary of approaching their nests and giving away the location — annoyingly so, as I have spent far too many fruitless hours watching horned larks do anything but go back to their nests.

Chestnut-collared longspurs hide their nests in much denser vegetation, making them difficult to see until the female explodes off the nest when someone approaches within one or two metres. Even then it requires sharp eyes to find a nest so well hidden under dense grass.

Once a nest is found, we check it every two to four days until it either fledges or fails. We count the number of eggs laid, the number of those that hatch, and the number of chicks that fledge. When the chicks are seven days old we weigh and measure them to assess their quality. Nest success has varied between years, with 50% of horned lark and 45% of chestnut-collared longspur nests successfully fledging chicks on average. While this may not seem very successful, both species make multiple breeding attempts in a season, building a new nest and laying a new clutch after one fledges or is discovered by a predator.

We also attempt to band the adults with unique colour-band combinations. These bands allow us to calculate the percentage of breeding birds that return in subsequent years. One of the great unknowns until recently is where different breeding populations spend their migration and wintering periods. Although we know the general winter range of each species, different breeding populations may take different routes or winter in different areas. Understanding this migratory connectivity may help us understand how land-use or climate change throughout the life-cycle may be related to population declines.

This chestnut-collared longspur pair has individual colour-band combinations. Monitoring how many colour-banded birds return in the years following banding is a measure of the population’s apparent over-winter survival. DAVID BELL

Small, lightweight VHF nano-tags are attached to birds using leg-loop harnesses in an ongoing collaborative study on grassland bird migration. When this chestnut-collared longspur heads south on fall migration, we hope that it will fly near a growing array of receiver stations across North America to provide detailed information on migration routes and wintering locations. LIAM SINGH

Tracking has gotten easier in the last several years as the size and weight of tags for birds has grown increasingly smaller. There is now a geolocator tag that can be attached to the back of a bird using a leg-loop harness. This tag uses a light sensor to record sunrise and sunset each day, and from that the bird’s approximate location can be calculated. Unfortunately, the tag must be retrieved from the bird to download this information, and horned larks are very wary of being re-trapped. Of the tags we have retrieved so far, two birds spent most of the winter in northern Colorado and southern Wyoming, migrating in the fall though Montana and the spring through the Dakotas. But a third bird appeared to spend most of the winter near Suffield.

This past summer I was able to expand this migratory connectivity work with collaborators from Saskatchewan and Montana through a wide and growing network called the Motus Wildlife Tracking System (motus.org). Motus uses individually coded radio-tags attached to the birds and radio-receiver stations that pick up the pings from the tags when birds fly by within approximately 30 km. The network of receiver towers is growing rapidly across the grasslands of Canada, the U.S., and Mexico. These tags do not need to be retrieved from the birds, so I hope to be able to get much more data on migration of grassland songbirds in the future.

Between Suffield and sites in Saskatchewan, in 2022 we deployed tags on horned larks, chestnut-collared longspurs, Baird’s sparrows, Sprague’s pipits and thick-billed longspurs. We have high hopes that the tags will begin pinging off towers as birds start their fall migrations! This work will continue to give us a fuller picture of how these species use habitat and are affected by agriculture and climate throughout their annual cycles across North America.

While the situation for grassland birds in Alberta and beyond seems dire, there are actions people can take to help. First, we need to conserve remaining native grassland wherever it occurs. This can be accomplished by donating to organizations that conserve and protect native prairie, as well as by letting your elected officials know about your concern for grassland protection. You can also support grassland conservation by buying grass-fed, grass-finished beef. By supporting ranchers using sustainable methods, you support operations that keep those grasslands from being plowed up. And finally, you can watch, appreciate, and spread the word about the unique and wonderful grassland bird community and the struggles it faces. For more information, please visit 3billionbirds.org and birdscanada.org/bird-science/grassland-birds-at-risk.

References

- Downes, C., P. Blancher, and B. Collins (2011). Landbird trends in Canada, 1968‐2006. Canadian Biodiversity: Ecosystem Status and Trends 2010, Technical Thematic Report No. 12. Canadian Councils of Resource Ministers. Ottawa, Ontario, Canada.

- Gage, A.M., S.K. Olimb, and J. Nelson (2016). Plowprint: Tracking cumulative cropland expansion to target grassland conservation. Great Plains Research 26:107-116.

- Stanton, R.L., C.A. Morrissey, and R.G. Clark (2018). Analysis of trends and agricultural drivers of farmland bird declines in North America: A review. Agriculture, Ecosystems and Environment 254:244-254.

- NABCI. North American Bird Conservation Initiative Canada (2019). The State of Canada’s Birds, 2019. Environment and Climate Change Canada, Ottawa, Canada. http://nabci.net/wp-content/uploads/2019-State-of-Canadas-Birds-1.pdf

Dr. Nancy Mahony is a research biologist with the Wildlife Research Division of Environment and Climate Change Canada, based in Edmonton. Her research program is focused on exploring the causes of population declines of grassland and aerial insectivore birds in western Canada and strategies for their conservation.

This article originally ran in Nature Alberta Magazine - Fall 2022.